The story of a “champion” submersible

Alvin's humble origins began alongside Cheerios and Wheaties

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

It became a champion submersible.

Alvin, the manned deep-diving vehicle operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and designed by General Mills – yes, the same company that gave the world Wheaties, the Breakfast of Champions – celebrates its 60th anniversary this June. Like the trailblazing athletes featured on the famous orange cereal box, Alvin boasts a legendary list of feats accomplished during more than 5,200 dives, including the discovery of hydrothermal vents, the location of a lost hydrogen bomb, and the exploration of the shipwreck Titanic.

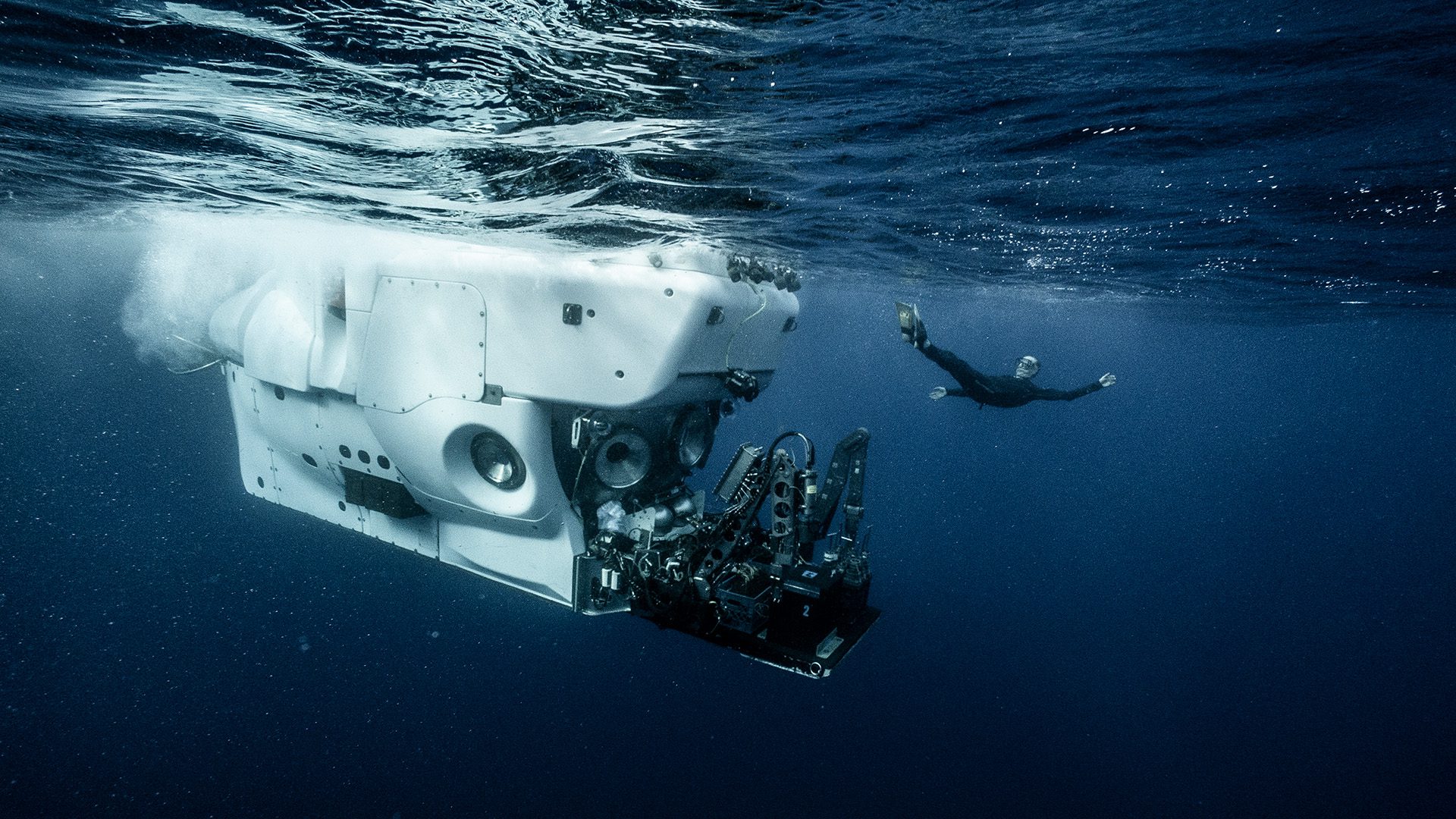

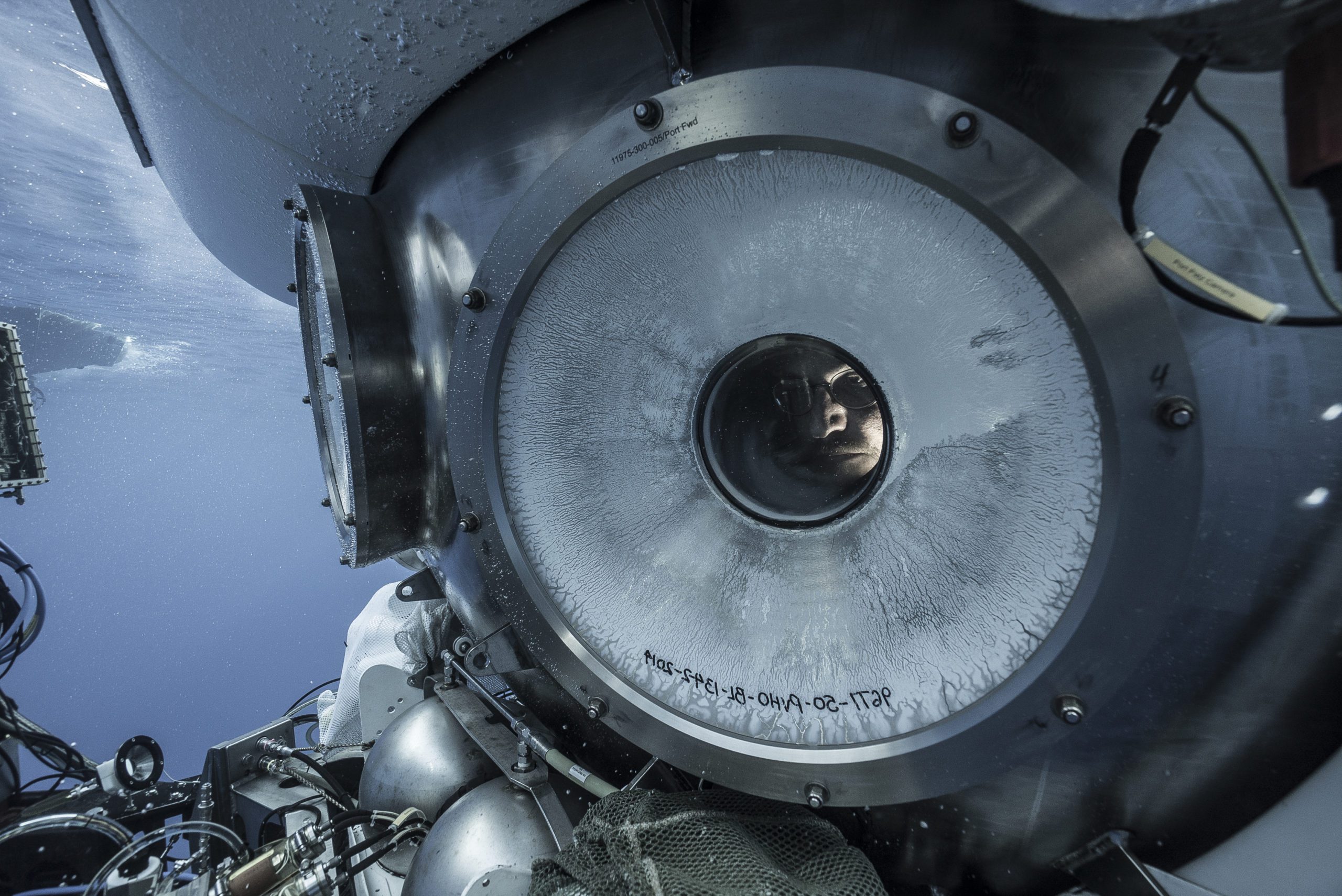

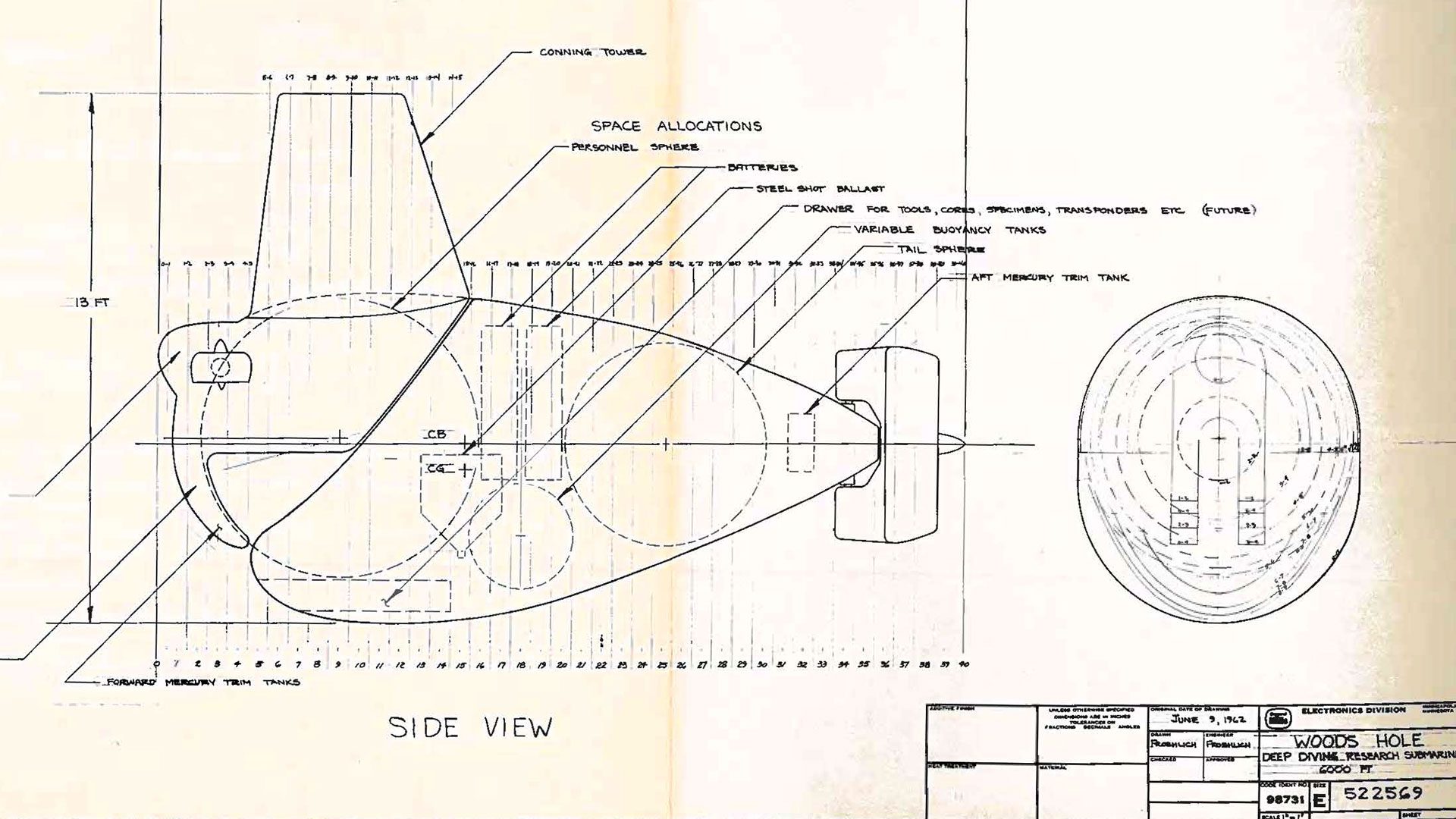

Designed to carry three passengers to the seafloor for research, Alvin came to be in the early 1960s during a time of enormous growth and possibility for General Mills. Food products were only a part of its mission; the manufacturer developed toys and board games, created the flight recording black box for airplanes in cooperation with a local university, and received U.S. military contracts to build high-altitude research balloons.

Alvin in various stages of the production process at General Mills. (Footage courtesy of WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“This was in the days when General Mills was in business without boundaries, (that) was the philosophy,” said engineer Harold Froehlich, who joined the company’s aeronautical research lab in the early 1950s. A Navy veteran of World War II, Froehlich gained oceanographic experience at General Mills developing a mechanical arm for an undersea military vessel, a project that spurred discussion for a smaller, deeper-diving submersible.

The sentiment was shared by the U.S. Navy and the oceanographic community, including WHOI physicist and oceanographer Allyn Vine, who inspired the submersible’s name. In May 1962, bidding to design and build a submersible came down to two companies: aerospace manufacturer North American Aviation and General Mills. Both were judged to be technically equal, but General Mills’ bid came in nearly $100,000 lower than its rival. For $498,500, General Mills received the contract to produce a first-of-its-kind undersea vessel, with the cost covered by the Navy and operations managed by WHOI.

During the next two years, Froehlich lead a team of engineers who overcame mechanical, structural, and weight issues that had plagued larger manned underwater vessels that could reach tens of thousands of feet in depth but were heavy and difficult to maneuver. Most importantly, with humans on board, Alvin’s safety provisions were paramount; the sub would need to be able to withstand crushing pressure at depth and allow for emergency escape if necessary.

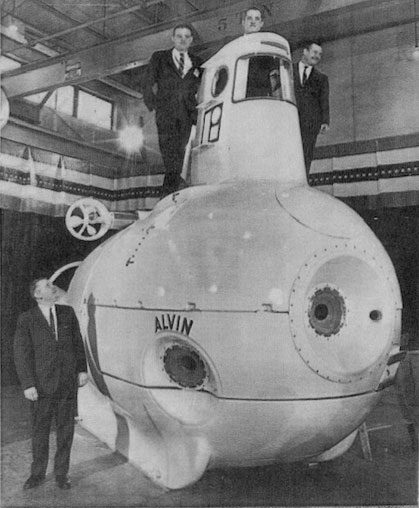

Harold E. Froehlich (left) stands beside Alvin, looking up at three crew members during the unveiling ceremonies. (Photo courtesy of the General Mills Archives)

In spring 1964, the submersible was assembled in the same room that General Mills built its specialized equipment for making Wheaties. Then the 22-foot-long submersible was trucked from Minneapolis to WHOI in two sections; Froehlich chose the submersible’s width of 8 feet because it was the legal limit for an object transported on a highway without special permits or an escort.

After WHOI scientists launched Alvin that June for shallow water test dives off Cape Cod, Froehlich climbed inside for one dive “to the great depth of 27 feet,” he said in an interview in the 1980s.

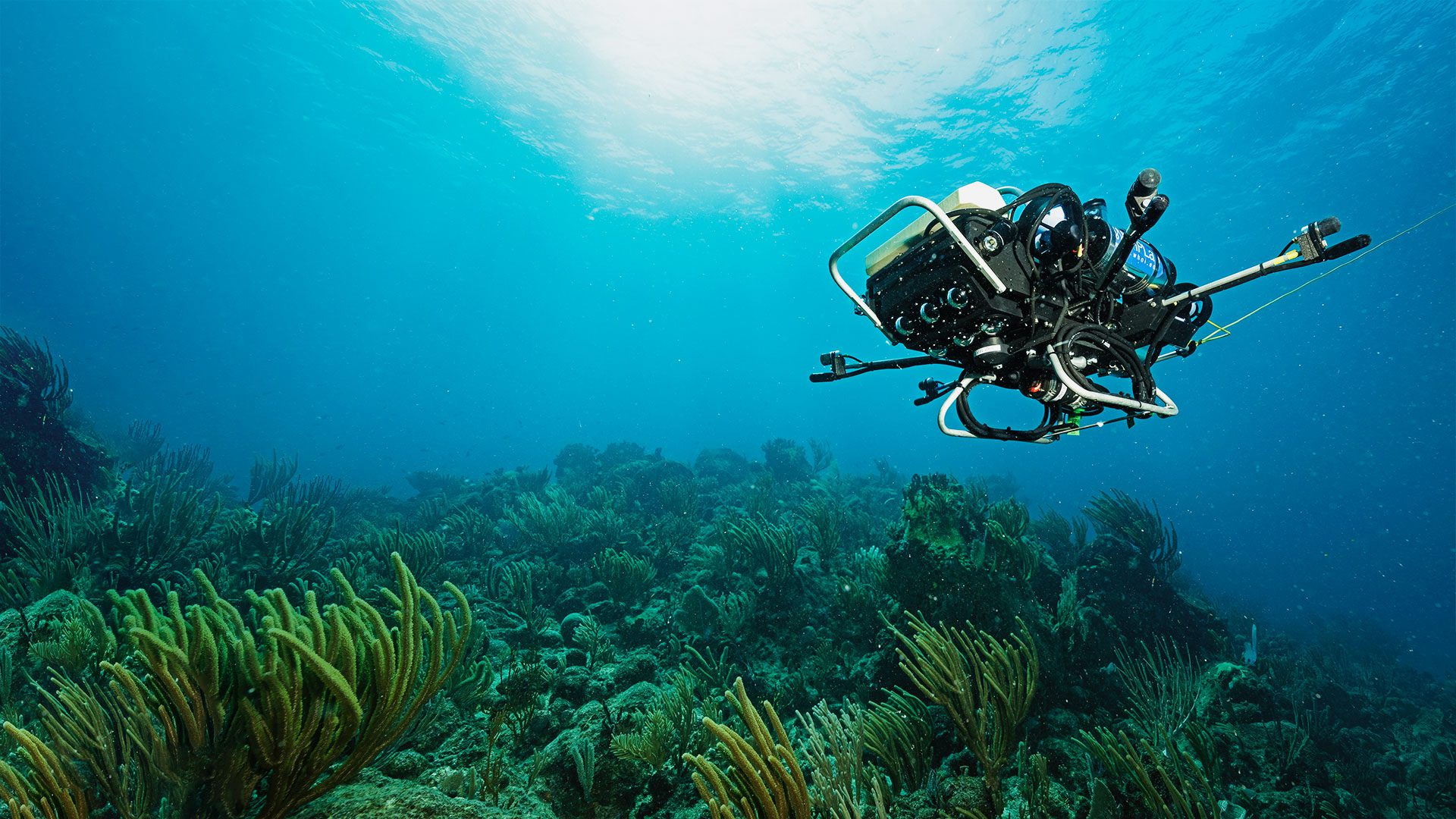

Today, the sub is still 8 feet wide, and with ongoing upgrades, now has a depth rating of more than 4 miles (6,500 meters). This allows researchers access to 99 percent of the seafloor and explore places like the Piccard Hydrothermal Vent Field (home of the world’s hottest and deepest known hydrothermal vent zone) and the Aleutian Trench (one of the most volcanically and tectonically active parts of the seafloor, access which helps in the study of connections between land, deep ocean, and sea surface). During six decades, more than 14,000 scientists, engineers, and observers have completed a dive in Alvin.

Froehlich, who died in 2007 at age 84 in his home state of Minnesota, remained proud of the submersible’s design roots at General Mills. “We worked hard to make Alvin simple and useful,” Froehlich said. “It’s very gratifying to have this country’s top marine and engineering personnel recognize the contributions of a vessel built on a shoestring budget in the heart of the Midwest."