Our eyes on the seafloor

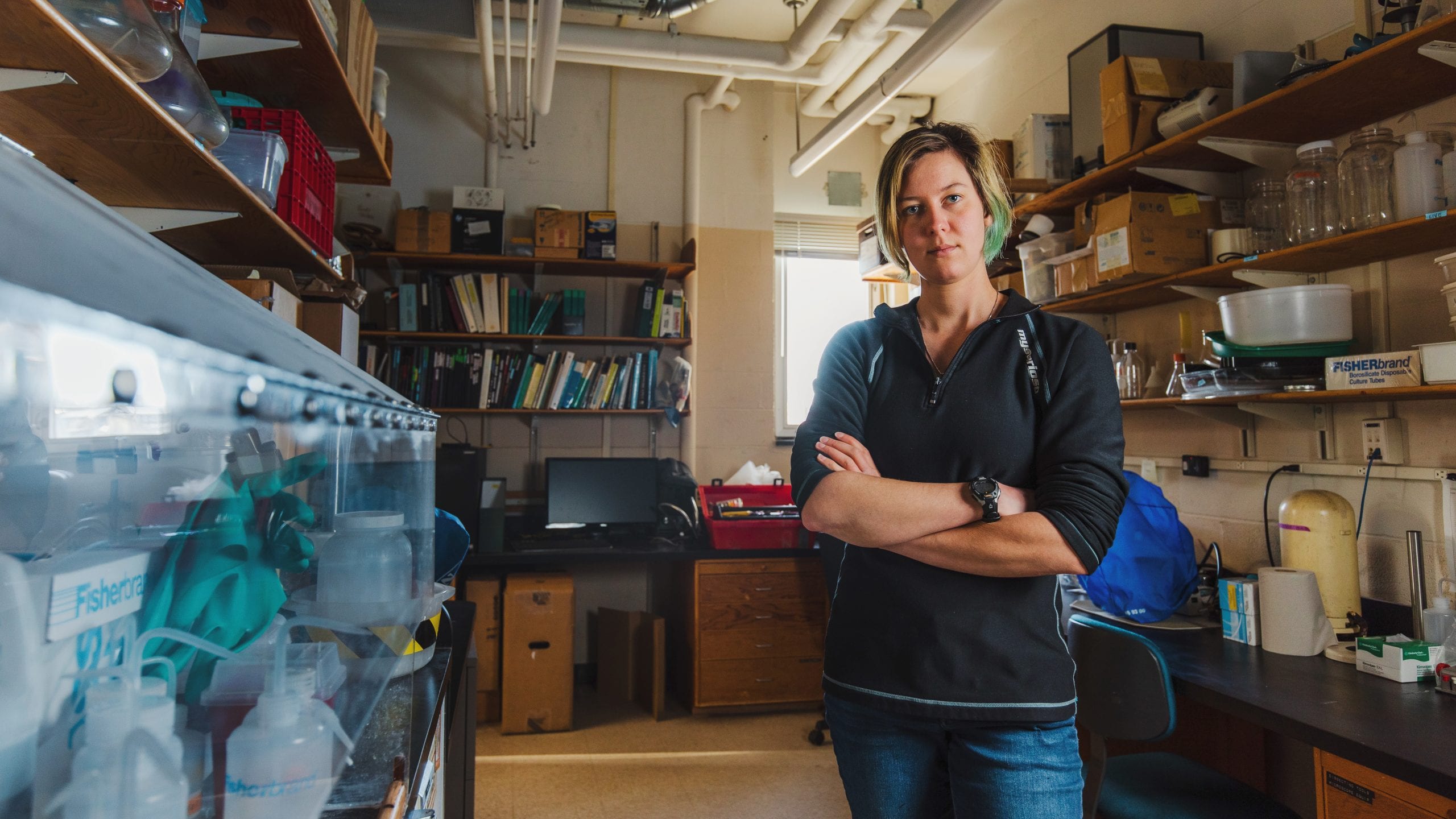

A Q&A with WHOI marine microbiologist Maria Pachiadaki on sampling the deep ocean with ROV Jason

By Hannah Piecuch | January 17, 2024

WHOI Associate Scientist Maria Pachiadaki studies the deep ocean, focusing on zones that lack both light and oxygen. In depths below 200 meters (656 feet), there are organisms that produce energy and new organic matter, but without photosynthesis or oxygen. She wants to understand how these organisms contribute to biogeochemical cycling—moving carbon and nitrogen through ecosystems—and where they live. This interview took place while Pachiadaki was at sea in July 2023 with remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason.

Tell us about your research.

What has fascinated me for years are oxygen-minimal zones in the midwater or mesopelagic zone—a layer ranging from 200 to 1000 meters (656 to 3,280 feet) deep. In some parts of the mesopelagic, there are areas that are practically anoxic (almost entirely lacking oxygen). Most of the organisms on Earth breathe, but there are some that don’t. Due to the logistics of getting to this part of the ocean, the carbon and nitrogen cycling haven’t been studied well in situ—or in place, without transporting them back to the ship, depressurizing them, and contaminating them with oxygen. I’m very interested in the functions of these species, how they contribute to biogeochemical cycling, and how the communities interact and disperse. Most of this takes place in the midwater, so not near the bottom. In my collaborations with WHOI scientist Julie Huber and Texas A&M professor Sarah Hu, and on past expeditions with my former postdoctoral advisor WHOI senior scientist Virginia “Ginny” Edgcomb, I also study sites on the seafloor, and that is when I work with Jason.

What is ROV Jason doing for you on this expedition?

On an expedition like this we rely on Jason for the majority of our sampling: It’s doing fluid sampling, collecting sulfites and ciliate mats—everything we want for biology and chemistry. For me, Jason is placing the mini Submersible Incubation Device (miniSID) on the seafloor, so it can draw water from the source that I want and conduct experiments at hydrothermal vents. The miniSID actually does an experiment similar to the one that Sarah Hu and her team are doing in the lab, but it does it right at the vent and then the instrument comes up with the samples stabilized. After the expedition, we will filter them and use a fluorescent microscope to count cells and compare the results we get from experiments done on the seafloor with the ones that were brought to the surface and the experiments done in the lab.

How have you used Jason on other expeditions?

My first expedition in 2011 was WHOI Mediterranean Deep Brines with Jason. I was involved because I was local PhD student from Crete. We were investigating the deep, hypersaline, anoxic basins—underwater “lakes” of extremely salty water with no oxygen. They have so much salt that they won’t take any more, and they are so dense that they cannot mix with the seawater above. Jason was coring the seafloor, and taking samples where you transition from normal salinity into moderate and hypersalinity.

Have you had any memorable experiences watching dives in the Jason control van?

Last year I was in the control van when they were taking a person from total newbie to making them part of the team, and it was really fascinating the care that goes into training. I was like, “Can I be a half-time scientist and half-time Jason Team? Can you train me to be one of you?” It’s pretty cool to see the Jason Team work together. They are on top of things. As a team, they are isolated from the rest of the world for weeks, so they have to do all the troubleshooting on their own. Of course, they have the scientists and the ship’s crew, but it’s a self-sustaining ecosystem. I have been impressed with the care and interest they show with the scientific instruments. I would think a vehicle group would just take care of their own instruments. But they care about the science, as well, and they understand the success of their entire team is associated with the success of the science. They provide amazing support.

How does access to a vehicle like Jason impact your scientific work?

It’s so important to everyone who does work in the deep ocean. Jason can operate almost 24/7, its pilots are safe and well rested, and incredibly skilled with driving and setting up experiments. A vehicle like Jason can map things, find new features we’re interested in sampling, and make discoveries. It is our eyes and hands on the seafloor.

This story was adapted from a blog post on the National Deep Submergence Facility site from PROTATAX23, an ROV Jason expedition to Axial Seamount led by WHOI Chief Scientist Julie Huber in July 2023. PROTATAX23 is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF OCE Award #1947776).