Teaming up for right whales

Teaming up for Right Whales

WHOI-NOAA collaboration aims to protect endangered species from lethal ship strikes and noise from offshore wind construction

By Elise Hugus | July 9, 2020

Illustration by Natalie Renier, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

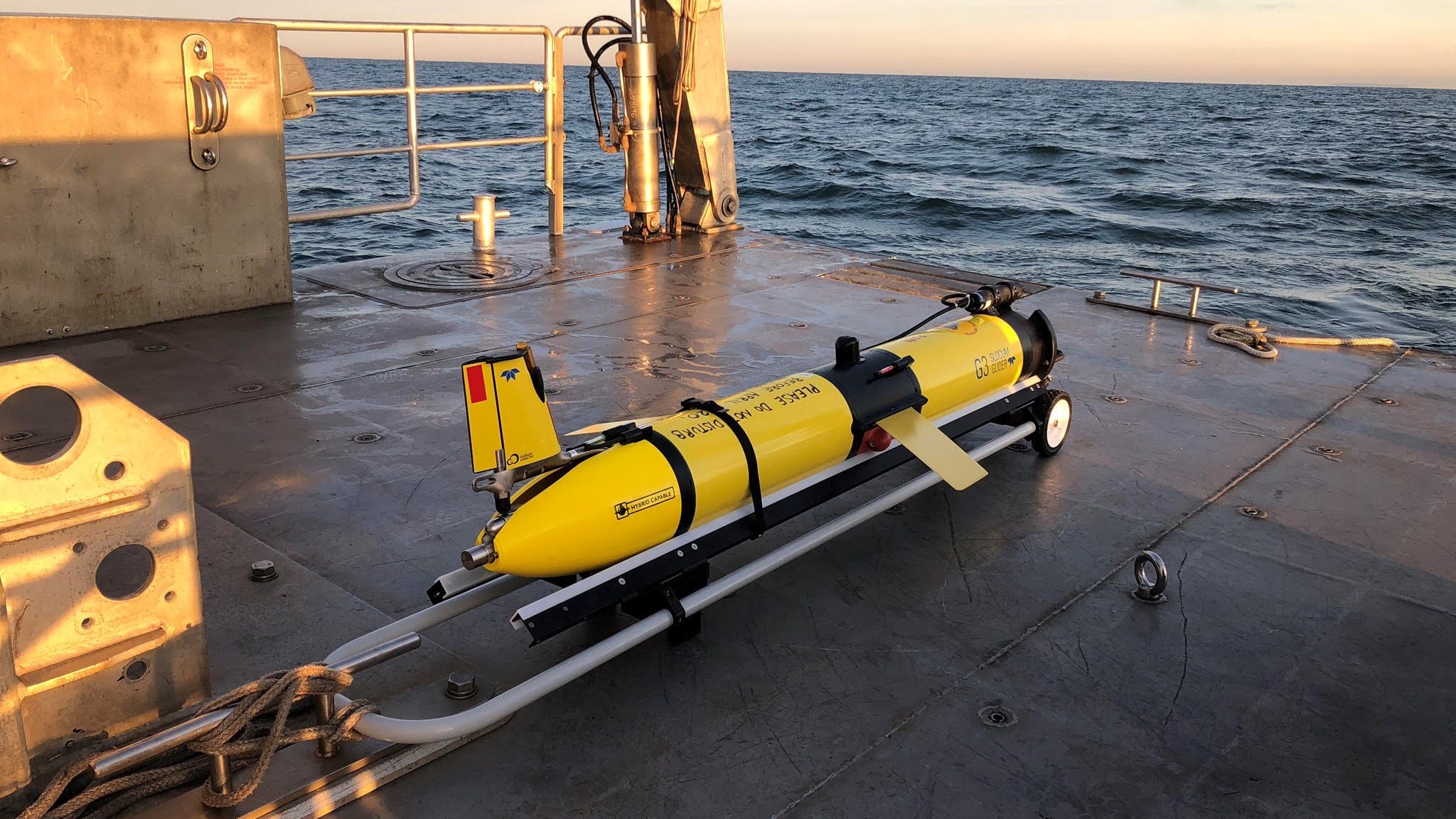

The yellow glider sits quietly on its sled during the five-hour voyage from Woods Hole, Mass. to the outer New England continental shelf. When the R/V Tioga arrives at an appointed latitude, WHOI biologist Mark Baumgartner wheels the sled to the back of the ship, and without much fanfare, slides the torpedo-like autonomous underwater vehicle into the depths. It’s soon out of sight, but not out of mind. Over the next few months, the glider will act as Baumgartner’s ears in the ocean, alerting him every two hours to the presence of marine mammals in its midst.

It’s just one of many Slocum gliders that Baumgartner has deployed through his collaboration with Sofie Van Parijs, a researcher at NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole. Combining their interests in passive acoustics, the pair has published a number of groundbreaking studies in the last decade, demonstrating gliders’ ability to detect anything from baleen whales to spawning cod in near real time.

That capacity is crucial for stopping lethal ship strikes as endangered North Atlantic right whales migrate through shipping lanes and fishing grounds. If a glider detects a right whale or other species of interest, it can send a text message to scientists and regulators, who may then send out an aerial survey for further verification, or issue a warning to ships in the vicinity.

Shipping and fishing are not the only industries concerned about interactions with endangered whales. Numerous offshore wind projects, slated for construction off the Northeast coast in the coming years, have pledged to mitigate impacts on marine mammals—and are looking to passive acoustics, mounted on gliders and moored buoys, to help them do so.

“This collaboration is hugely valuable and really exciting,” says Van Parijs, who leads NOAA’s Northeast Passive Acoustics Research Group. “The whole brilliant thing about WHOI is its technical capacity, finding new and innovative ways of doing science. There’s no way we could do any of this without our partnership with Mark.”

The advantages of gliders are many: the vehicles spend most of their time underwater, all but immune to the storms that plague ships and planes during North Atlantic winters. They can measure the ocean for months at a time, covering hundreds of miles at a fraction of the cost of aerial and shipboard surveys. While quietly see-sawing their way through the various layers of the ocean, the gliders collect oceanographic data like salinity, temperature, and the presence of phytoplankton.

Passive acoustics are a more recent innovation. A decade ago, working with WHOI scientists and engineers Dave Fratantoni, Mark Johnson, Jim Partan, and others, Baumgartner added a digital acoustic monitoring (DMON) device to the glider. The DMON matches the sounds it detects with those stored in an on-board database. It then sends an “educated guess” at what species made the sound, along with a visual representation similar to musical notes, to trained reviewers back on land. The verified results are then uploaded to a website Baumgartner created for the purpose, Robots4Whales.

Over the winter and spring of 2020, data transmitted by the researchers’ five gliders and two moored buoys revealed right whales congregating up and down the U.S. East Coast, often near busy shipping lanes and fishing areas. In previous years, Baumgartner and WHOI colleagues Tammy Silva, Aran Mooney, and Laela Sayigh used passive acoustics on gliders to survey dolphins in NOAA’s Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

These marine mammal detection strategies are starting to make waves beyond New England. Baumgartner is involved in similar whale-monitoring projects in southern California, Alaska, and Chile. In collaboration with researchers in the U.S. and Canada, the passive acoustic glider systems are part of a comprehensive surveillance effort to protect right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

“We’re building a network throughout the U.S. and Canadian east coasts with many partners so we will better understand where right whales are at any given time,” says Baumgartner. “It’s really gratifying to have this marriage of technology and science be adopted for real-world conservation purposes.”

Funding for this research comes from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service, the United States Navy’s Office of Naval Research and Living Marine Resources Program, the Department of Defense’s Environmental Security Technology Certification Program, and the WHOI Ocean Life Institute.