REMUS Group gets new director

A conversation with WHOI’s Carl Hartsfield

By Millie Dent | September 19, 2020

Carl Hartsfield is the new director of the REMUS group at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He joins WHOI after 30 years in the Navy, serving as a submarine commanding officer, a submarine commodore, and executive officer to one of the combatant commanders at U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) in Omaha, NE. Though his position is new, Hartsfield is no stranger to WHOI: He studied autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and their applications as a master’s graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in the early 2000s.

What’s it like to be back at WHOI after almost 20 years?

It's both exciting and heartwarming. Even though I had Navy business here and my wife Leigh Ann and I took vacations on the Cape, we weren't immersed in the Institution and the community. Now that we are, it just feels like home. On campus there are so many new faces, but a lot of old ones too.

How did you initially become interested in AUVs?

I'm old enough to remember thinking about the Titanic before and after Bob Ballard rediscovered it. What was thought to be, and what was found, were so different, and that attracted me to Woods Hole as a place of discovery. I was lucky enough at a very early age in my Navy career to be trusted to manage a lot of groundbreaking technology and that’s when I learned to appreciate untethered autonomous devices and what they might do in the future. Then when I became a graduate student here in 2005, I realized I had a choice. As a Navy-funded student, I could choose any group I wanted to work with and I chose the REMUS group because of the people and their common vision. That group of engineers were giants to me then, and they still are today. I'm really lucky to be able to work with them again and be charged with carrying on their legacy alongside the bright engineers we have here today.

Why is the REMUS group critical to WHOI’s mission?

The REMUS group is a growth engine that WHOI needs to harness. If you say the word “REMUS” to people in the unmanned undersea business, a picture of a yellow torpedo pops into their head. We need to capitalize on the creative genius that built that successful family of systems and not simply live on the dividends it created. If we are lucky and committed, people will start to associate REMUS with something new or different – certainly something innovative. The point is not to get stuck in your vision, otherwise you become stagnant and irrelevant.

What development projects are you most interested in?

It's the long endurance and persistent missions that interest me the most. Building vehicles that can survive, operate, and succeed in the ocean on longer timescales that are more comparable with sea gliders. Those projects will require us to push the envelope in autonomy, energy, navigation, bio-fouling, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. All of those technologies are emerging right now, but very few of them are field proven. I believe that successful, communicated repetition in those areas will build confidence that people with resources want to see, and that will lead to further investment.

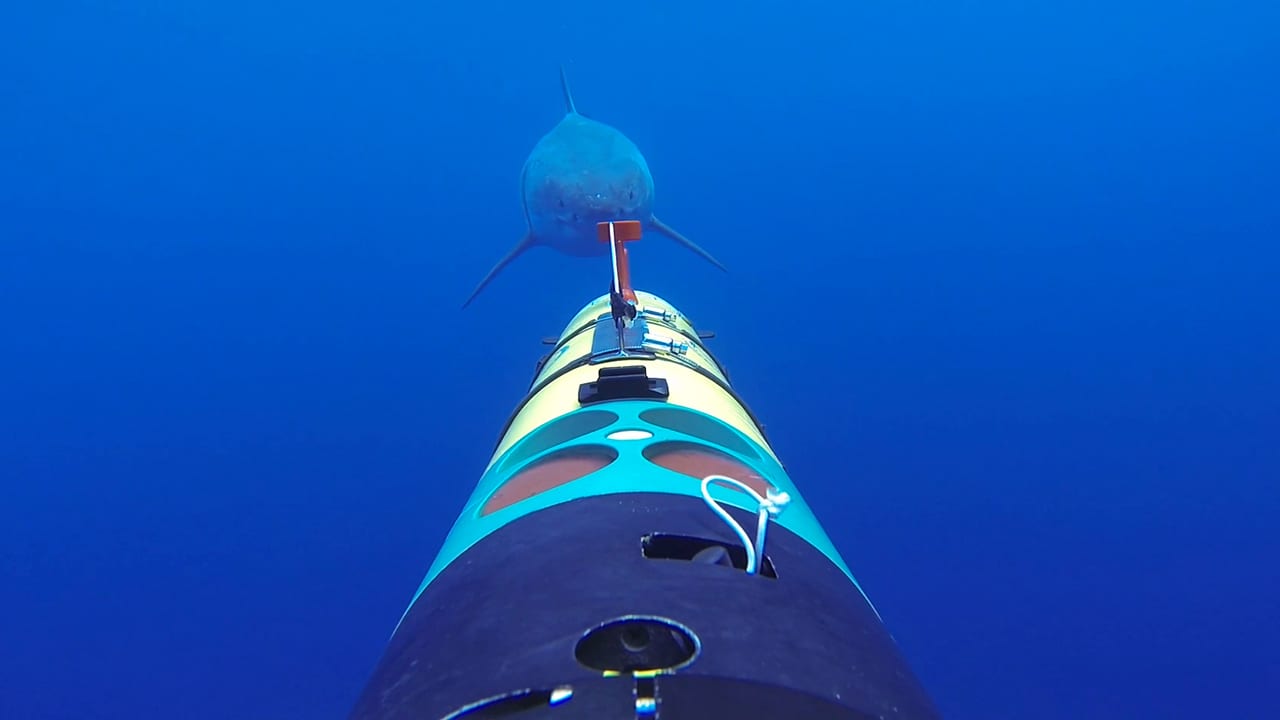

Thanks to the REMUS SharkCam, recently published research has shed light on the behavior of basking sharks. What other sorts of projects is the SharkCam working on?

WHOI’s Oceanographic Systems Lab (OSL) really did something transformational with SharkCam. If it moves in the ocean within a reasonable speed, SharkCam and its tagging technology are really the only way to get those unique shots. They've done sharks, they've done turtles, and they've now done basking sharks. I think whales are probably on the horizon. But really, the key technology with SharkCam is the free-swimming AUV that follows a tag so anything you want to observe in 3-D in the ocean at ocean animal speeds, SharkCam is game. It doesn't even have to be an animal.

What do you hope to accomplish as the new director of the REMUS group?

Like any tech development organization, we have to find the right mix of incremental innovation and disruptive innovation. For example, a customer may be willing to fund adding another battery tray to a vehicle, but are they willing to go further and change the density and chemistry of the battery? One has a small, known payoff; the other, a potentially bigger one – but with more risk. Do you iterate to success or take big jumps by betting on new ideas that are less developed? We have to get that mix right in OSL, and be able to take some calculated risk knowing that all the ideas won’t pan out.