Featured Photos

- MIT-WHOI Joint Program graduate students Alice Alpert (left) and Liz Drenkard (center), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service representative Kelsie Ernsberger (right), snorkel above a large coral at an atoll in the central equatorial Pacific in 2012. Alpert, Drenkard, and WHOI scientist emeritus George Lohmann, with the conservation organization Pangaea Exploration, sailed 2000 miles to these remote coral islands. They sampled seawater and coral and deployed instruments, part of a larger study by WHOI scientists Anne Cohen, Kris Karnauskas, and Delia Oppo aimed at gaining a better understanding of climate change and potential impacts of ocean warming and acidification on coral reef communities. (Photo by Chip Young, NOAA)

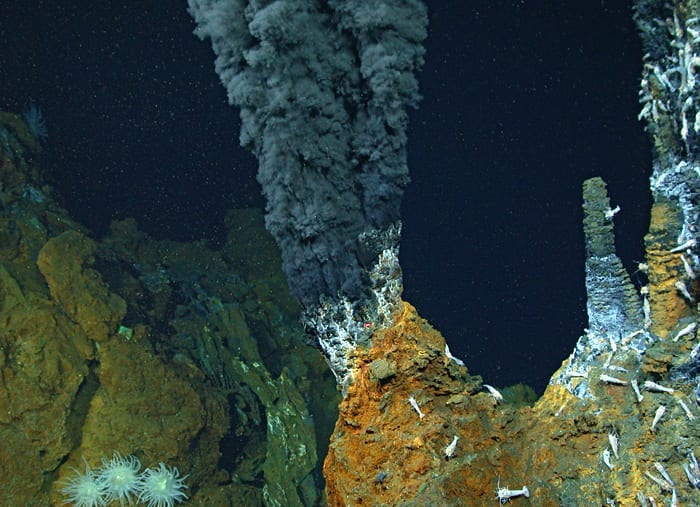

- Deep-sea shrimp thrive at one of the planet's hottest black smoker hydrothermal vents, where the temperature of expelled fluids measured 400°C (about 750°F). The "smoke" consists of dark, fine-grained particles suspended in the fluids that come out of solution as they cool and mix with cold seawater. Remotely-operated vehicle Jason captured the image in January 2012 during an expedition led by WHOI marine geochemist Chris German to study the deepest-known hydrothermal vents, at the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean. (Photo courtesy of Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

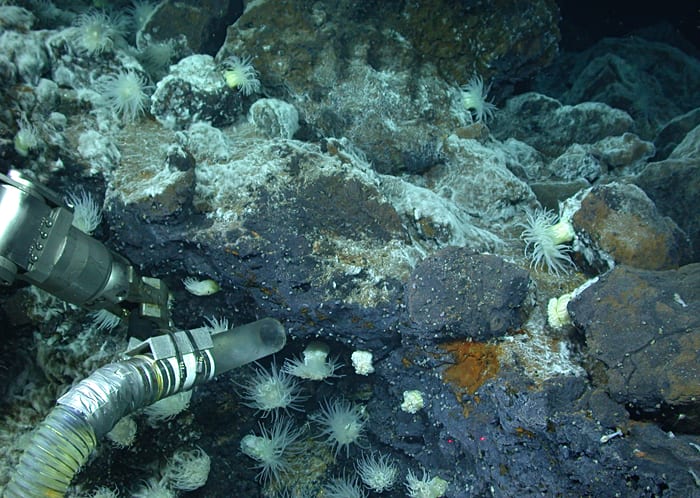

- Hydrothermal vents three miles down support a variety of life based on chemical energy. This image from a 2012 expedition to the Mid-Cayman Rise led by geochemist Chris German shows microbial mats that look like bird droppings clinging to rocks (top) and a newly discovered species of eyeless shrimp (lower right). Tentacled anemones (throughout image) catch and consume shrimp, and very small snails (white dots) graze on microbes on the grey sulfide rocks. The suction-tube sampler of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's ROV Jason collects a sample of snails (left center, just below Jason's manipulator hand). The red laser dots (bottom, right center) are 10 centimeters (3.9 inches) apart. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The science crew on board any UNOLS (University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System) research vessel spends part of the first day of every cruise in safety briefings and drills. One activity involves practicing how to put on a survival suit. Here, scientists, engineers, and students on board R/V Atlantis for the OASES 2012 cruise show off their "Gumby" suits, as the gear is also known. The team recently traveled to the Mid-Cayman Rise to explore the deepest hydrothermal vents in the world using the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason. (Photo by Julia DeMarines, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Senior Scientist Lloyd Keigwin, whose research focuses on climate and oceanographic change based on studies of deep-sea sediments, is among 14 new fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) elected in the field of Geology and Geography. AAAS officials cited Keigwin for "distinguished contributions to the study of the ocean's role in climate change and for national and international leadership." Shown here in the Institution's Seafloor Samples Lab, Keigwin was among the first to document a change in Atlantic water mass properties during the last ice age. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Scientists aboard the R/V Atlantis recover an ocean bottom seismometer (OBS) off the Galapagos Islands. Seismometers measure movement in the Earth's crust, and scientists use data from these instruments to calculate the energy released by earthquakes. A recent $1 million grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation will allow a WHOI team led by geologist Jeff McGuire and John Collins, director of WHOI's OBS Lab, to build and install the first seafloor geodesy observatory above one of the most dangerous faults in North America, the Pacific Northwest's Cascadia fault. (Photo by Jeff McGuire, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

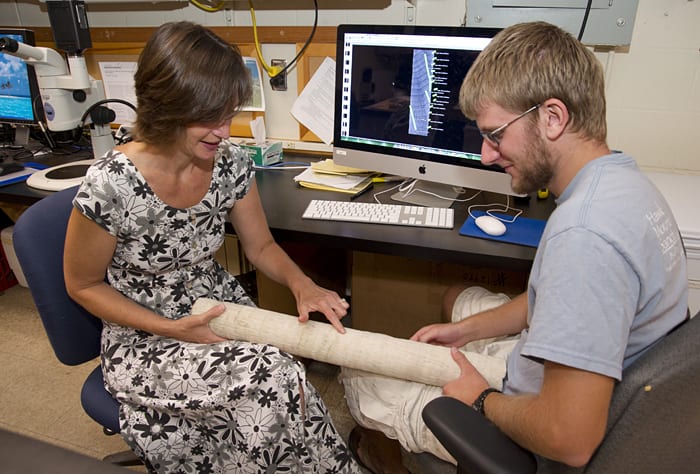

- MIT/WHOI Joint Program student Camilo Ponton and WHOI geologist Liviu Giosan examine a sediment core they used to reconstruct the history of India’s monsoon over the past 10,000 years. Collected from near the mouth of the Godavari River by the National Gas Hydrate Program of India, the core contained remnants of the plants that were abundant on land during the accumulation of the sediment. Ponton, Giosan, and colleagues found that an extended arid period around 4,000 years ago, followed by highly variable monsoons after 1,700 years ago, probably contributed to the development of sedentary agriculture in India. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

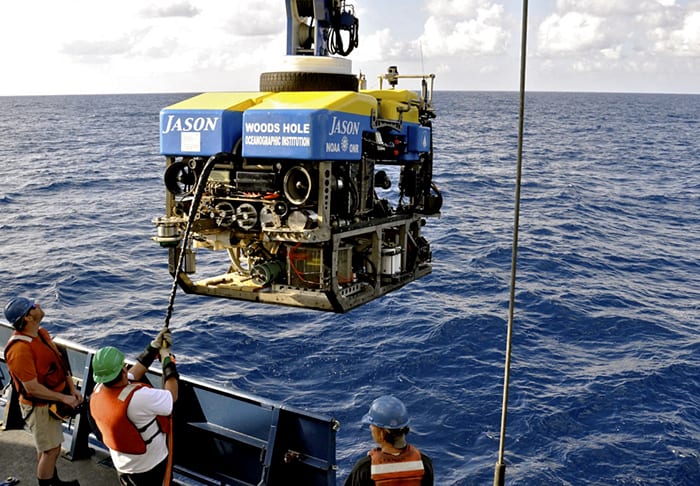

- When WHOI geochemist Chris German assembled a sea-going science team in January that could put in long hours and not balk at work in cold, dark places, he called on one of the toughest oceanographic tools he knows—remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason. The vehicle, lowered from the side of the research vessel Atlantis and directed by a crew of 10 working from the ship, spent hundreds of hours exploring the Mid Cayman Rise in the Caribbean, Earth’s deepest spreading center, in January 2012. Jason was the scientists’ eyes and hands on the seafloor, capturing thousands of photos and hours of high-definition video, mapping the seafloor terrain, and sampling fluids, sediments, rocks, and marine organisms. (Photo by Julia DeMarines)

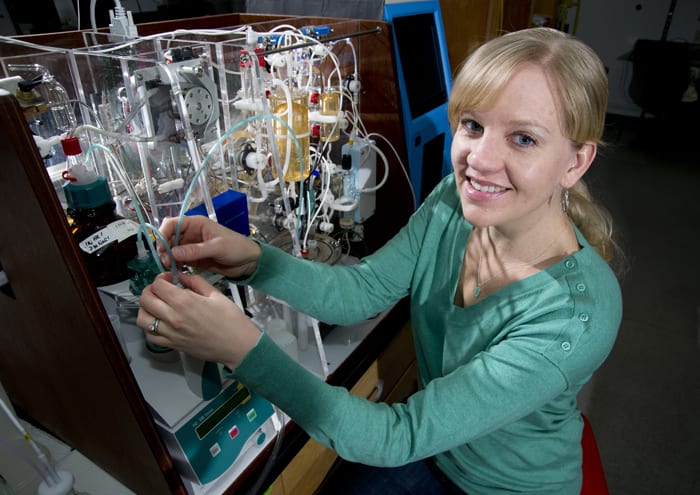

- WHOI postdoctoral researcher Katie Shamberger makes adjustments to VINDTA (Versatile INstrument for the Determination of Total inorganic carbon and titration Alkalinity) in the lab of associate scientist Dan McCorckle. By making fine measurements of those two paramenters (inorganic carbon and alkalinity), the instrument allows Shamberger to precisely calculate seawater pH and CO2 levels in seawater. The Southern California native studies coral reef ecosystems and how the ocean ecosystem as a whole responds to changing carbon dioxide levels as a member of Associate Scientist Anne Cohen's lab. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Scientists have predicted that ocean temperatures will rise in the equatorial Pacific by the end of the century, wreaking havoc on coral reef ecosystems. But a new study published by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution scientists Kristopher Karnauskas and Anne Cohen in the April 29 issue of the journal Nature Climate Change shows something different. Climate change could cause ocean currents to operate in a surprising way and mitigate the warming near a handful of islands right on the equator. As a result these Pacific islands may become isolated refuges for corals and fish. (Photo courtesy of Anne Cohen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Scientists dug pits up to 10 feet deep in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to expose layers of ice that are laid down snowfall by snowfall, year after year. The deeper the scientists dig, the further they go back into the past. MIT/WHOI Joint Program graduate student Alison Criscitiello is reconstructing the history of how sea ice has formed off the Antarctic coast by analyzing a chemical in these ice layers called methanesulfonic acid, or MSA (see video). She is working with glaciologists Sarah Das from WHOI and Ian Joughin of the University of Washington, seen here in the pit. With backlighting, layers in the ice become easy to see. (Photo by Ali Criscitiello, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

WHOI marine geochemist Chris German (right) and doctoral student Matt Hodgkinson of the National Oceanography Centre in England study a map of the seafloor from the Mid-Cayman Rise, an undersea mountain chain as much as 6,800 meters (4.2 miles) beneath the surface of the Western Caribbean Sea. In January 2012, German led an international expedition using the remotely operated vehicle Jason to return to, and sample, newly-discovered hydrothermal vent fields along this ultra-slow-spreading ridge, a region where two of Earth’s tectonic plates move apart and new material wells up from the interior.

(Photo courtesy of Julia DeMarines)- A recent, routine audit provided an opportunity for WHOI scientists to dig out some old equipment and reminisce about former successes. Here, Steve Swift, Tom Bolmer, Hartley Hoskins, and Ralph Stephen (left to right) hold a reunion around a wall-lock well geophone. Instruments like this clamp sensitive vibration sensors inside boreholes drilled deep into the seafloor. This particular geophone was deployed from the D/V Glomar Challenger in March 1977 south of Bermuda to conduct the first offshore offset vertical seismic profile (VSP) experiment to study the propagation of sound through Earth's crust. Today, VSPs and offset VSPs are routinely conducted by the offshore petroleum exploration industry. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Water is vital to all known forms of life on Earth, but it also plays a fundamental role in processes deep beneath the seafloor. Water in Earth's mantle enables tectonic plates to move and drives mantle melting and volcanism—processes that create and sustain the continents and atmosphere. In early 2012, WHOI's Dan Lizarralde, Nathan Miller, and Helen Feng sailed on the research vessel Marcus Langseth, towing air guns (shown here) over the Mariana Trench, a place where water trapped in the subducting Pacific Plate is being recycled into mantle. Sound energy from the air guns traveled about 20km (12 miles) beneath the seafloor and was recorded by ocean bottom seismometers 400km (250 miles) away. The scientists are using the data to create images of the subducting plate, which will help them understand how much water is recycled into the mantle at subduction zones and how water becomes trapped in subducting plates. (Photo by Nathan Miller, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A person uses a piece of wood to strike a lithophone, an instrument made of solid stone by Native Americans between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago. When struck, the lithophone emits a pure tone, like a bar on a xylophone. Amateur archaeologist Bill Moody brought two lithophones to WHOI in January 2012 for a closer look by WHOI scientists Henry Dick, Horst Marschall, and Ken Foote, who advised him on how the stones’ composition might affect their acoustic properties. Moody had the stones in his collection for years, but thought they were pestles used to grind grain or nuts until archaeologist Duncan Caldwell recognized and described them as lithophones. Prehistoric, portable lithophones of this shape have been found in the Sahara and Equatorial Africa, but these are the first identified from North America. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

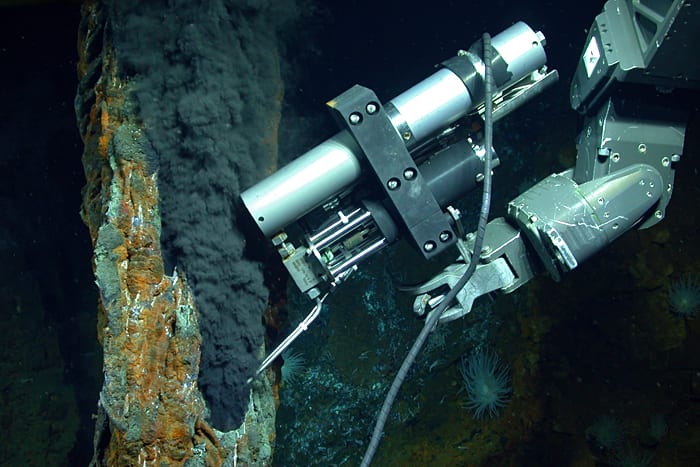

- During an "Oasis" cruise to the Mid-Cayman Rise in January 2012, the manipulator arm of the remotely operated vehicle Jason placed the intake tube of an isobaric gas-tight sampler (IGTS) into the stream of fluid gushing out of a hydrothermal vent. The fluid contains gases that are in liquid form because of the high pressure of the deep ocean. In the past, bringing such samples to the surface resulted in loss of the gaseous portion. WHOI scientists and engineers developed the IGTS to keep samples of vent fluid at high pressure until they can be brought to a lab for analysis. WHOI geologist Chris German led the expedition, which visited the deepest known hydrothermal vents in the world. (Photo courtesy of Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In January 2012, an international research group aboard R/V Atlantis completed an expedition to study the world's deepest known hydrothermal vents, at the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean. The group, led by Chris German of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, collected samples and images 2300 and 5000 meters deep using ROV Jason (just visible at the bottom). At the site shown here, called "The Furry Walls," long filaments of microbes attached to sulfide rock billow in the chemical-enriched water flowing from the seafloor. The microbes use chemicals instead of sunlight as an energy source. (Photo courtesy of Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI scientist Anne Cohen and Summer Student Fellow Chris Kelly study the core of a coral taken in Palau, a coral reef archipelago located in the far western tropical Pacific. For his summer research project, Kelly studied how corals on Palau grow in response to climate variability in the Pacific, which experiences water temperature warming and cooling cycles about every 20 to 30 years. He used CT scans to make internal, three-dimensional images that allowed him to measure the corals' growth rates over the last century. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In July, a group of WHOI scientists and engineers led by Fiamma Straneo and Sarah Das deployed a REMUS 100 "ICEBOT" in Saqqarliup fjord in Southwest Greenland. Their work was part of a unique study to measure water discharge from the nearby glacier and to investigate the highly variable conditions in the "red zone," an area less than 1 kilometer from the calving front of the glacier caused by meltwater runoff into the fjord. (Photo by Amy Kukulya, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- No, this isn't a preview of winter to come. This is a beautiful summer day—in Antarctica, where WHOI glaciologist Sarah Das, MIT/WHOI Joint Program graduate student Ali Criscitiello, and colleagues are studying whether climate change is affecting the formation of sea ice in the waters around the continent and speeding the flow of glacial ice to the sea (see video). Scientists dug pits up to 10 feet deep in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to expose layers of ice that are laid down, snowfall by snowfall, year after year, to reconstruct the history of how sea ice has formed off the Antarctic coast. (Photo By Sarah Das, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Researchers searched for signs of deep-sea eruptions in the rocks they collected during a spring cruise to hydrothermal vent sites along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Older rocks look dull, while freshly-erupted rocks have a glassy sheen, evidence of more recent volcanic activity. Pete Liarikos (right), boatswain on the research vessel Knorr, operated the rock dredge while researchers and students waited to take a closer look. They collected several hundred pounds of rocks in the dredge's chain bag during the month-long expedition. (Photo by Ellen Roosen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI researchers Trevor Harrison (left) and Richard Sullivan push a Vibracore-driven sediment corer into the mud of Basin Bayou on the Florida panhandle, as guest graduate student Jess Rodysill (Brown University) observes. The three are working with WHOI geologist Jeff Donnelly and the Coastal Systems Group to analyze how coastal sediments accumulate over time, reflecting climate conditions. The Vibracore's motor drives the core farther into the mud than people can push, allowing for a longer core and thus a longer history of sediment accumulation at the site. (Photo by Lance Croft, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Brown University graduate student Jess Rodysill, guest student Lance Croft, and WHOI researcher Richard Sullivan (left to right) set up an aeolian (wind-blown) sediment trap this summer on Florida's Santa Rosa Island. The traps were constructed in Woods Hole in partnership with Cape Abilities and record changes in aeolian processes over time and with changes in wind speed and direction. The data will help scientists in WHOI's Coastal Systems Group and elsewhere model the formation and evolution of barrier islands in order to better predict the impacts of changes in such variables as sea level and storm frequency. (Photo by Trevor Harrison, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

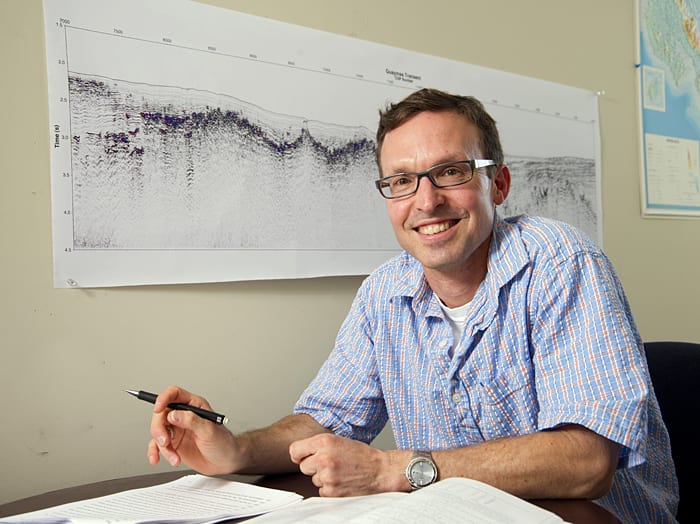

- Scientists have long thought that new ocean crust was only formed at spreading centers, where tectonic plates separate and allow magma to emerge from below. WHOI geophysicist Dan Lizarralde recently discovered locations in the Guaymas Basin beneath the Sea of Cortez where magma intrudes up into layers of sediment many kilometers from the nearest spreading center. Lizarralde and colleagues used seismic imaging (background) and a new device made by engineer Marshall Swartz to examine the seafloor and below in order to identify the new process of crust formation. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

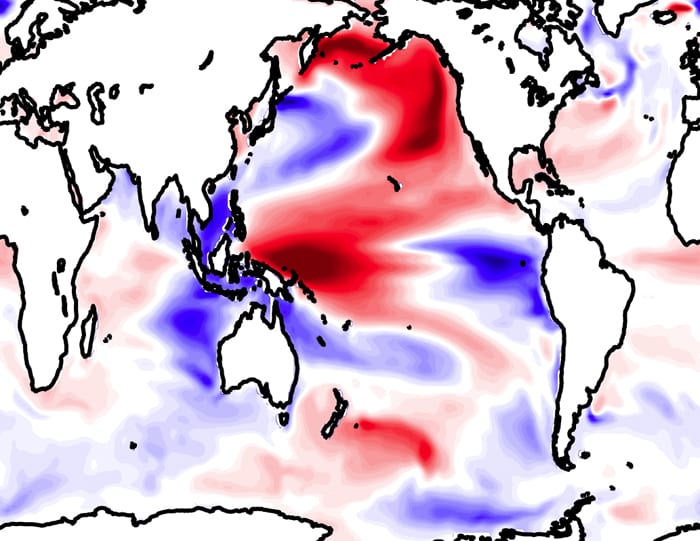

- Regular changes in sea-surface temperature in the Pacific Ocean, such as , such as El Niño and La Niña, influence precipitation and storms over a wide swath of the globe. Recently, Kristopher Karnauskas and colleagues found model-based evidence for another natural cycle , the Pacific Centennial Oscillation (PCO), which repeats on 100-year timescales. In one phase of the PCO (shown here), warmer temperatures (red) predominate across the western equatorial and northeastern Pacific; cooler temperatures predominate in the other. In November, Konrad Hughen sampled coral skeletons in Micronesia looking for evidence of temperature changes caused by the PCO. If confirmed, the PCO adds to understanding of how human actions can interact with naturally occurring climate patterns. (Image created by Kris Karnauskas, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The golf-ball-size slate pencil urchin, Eucidaris tribuloides, belongs to the only group of sea urchins known to have survived the Permian-Triassic extinction that occurred about 252 million years ago. Only about 4 percent of all sea-dwelling species survived that event, which has been linked to ocean acidification caused by global increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide. Postdoctoral scholar Justin Ries, working with scientists Anne Cohen and Dan McCorkle, studied how increased levels of atmospheric CO2 affect modern-day marine species (including Eucidaris) that use calcium compounds as building blocks in their spines, shells, or other structures. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Seafloor sediments contain millions of tiny shells of foraminifera—single-celled ocean organisms that lived, died, and sank to the ocean bottom over the ages. The fossil shells (seen here through a dissecting microscope) contain chemical clues to ocean temperature and rainfall when and where when the organisms lived. Paleoceanographer Delia Oppo, geologist Liviu Giosan, and their students have used fossils like these to discern patterns of Indian monsoons and ocean oscillations over several thousand years, shedding light on past changes in climate and how they affected human cultures. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.