Extinction of Neanderthals Was Not a Climate Disaster Scenario

September 26, 2007

For the past few decades, scientists have offered several competing theories for what led to the extinction of the Neanderthals, with much of the debate focusing on the relative roles of climate change versus conflict with modern humans. Now one theory can be ruled out.

New research by a multidisciplinary, international teamincluding paleoclimatologist Konrad Hughen of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institutionshows that Neanderthals did not die out at a time of extreme and sudden climatic change, as some researchers have suggested.

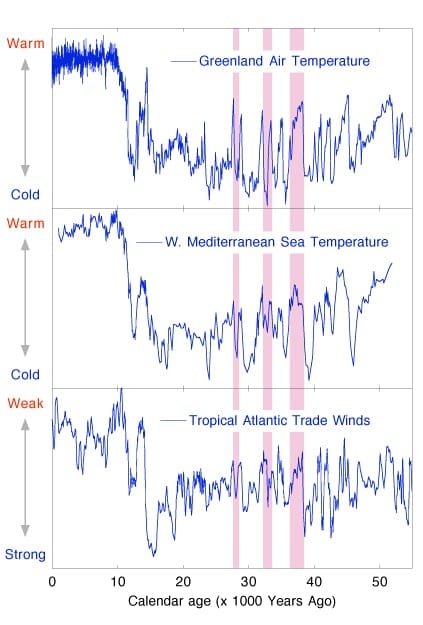

Comparing the dates of the final Neanderthal occupation of Gorham’s Cave on Gibraltar with paleo-climatological records drawn from Greenland ice cores and from Atlantic seafloor sediments, Hughen and colleagues concluded that two proposed dates (roughly 28,000 and 32,000 years ago) both fall within climate intervals that were not particularly cold or otherwise severe.

Specifically, the proposed dates do not coincide with what scientists know as “Heinrich Events,” when vast quantities of icebergs spilled into the North Atlantic, blanketed it with fresh water, and disturbed oceanic and atmospheric circulation to cause abrupt climate changes.

Another more controversial proposal suggests that the last Neanderthals may have died out as recently as 24,000 years ago. If that timeline is true, it did coincide with a period of major climate shifting, but the changes were much more gradual and incremental, possibly allowing them to adapt and migrate as they had done before.

The younger date “would imply a greater role of climate in Neanderthal extinction, not necessarily directly but perhaps in the form of climate-driven intensified competition as a result of increased southward human migration from higher latitudes,” the scientists wrote.

The research analysis was led by Chronis Tzedakis of the University of Leeds; with contributions from Hughen, Isabel Cacho of the University of Barcelona, and Katerina Harvati of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. The results were published in the September 13 issue of the journal Nature.

Although scientists have been expanding the records of past climate, correlating them with anthropological and archaeological findings has often been difficult. Tzedakis noted that “there are three main limitations to understanding the role of climate in the Neanderthal extinction: uncertainty over the exact timing of their disappearance; uncertainties in converting radiocarbon (14C) dates to actual calendar years; and the chronological imprecision of the ancient climate record.”

“Our method circumvents the last two problems,” said Hughen. Basically, the researchers did not attempt to relate the dates of the disappearance of Neanderthals to a calendar year, but directly to what the climate record tells us about the environment.

From ice cores and sedimentary records, Hughen and other paleoclimatologists can derive information about past temperatures and the amount of moisture in the atmosphere to paint a general picture of global climate. Radiocarbon-dated events may be difficult to calibrate exactly with calendar years, but geologic, climatological, and paleontological records can be mapped to each other.

“In this case, we were able to provide a much more accurate picture of the climatic background at the time of the Neanderthal disappearance,” Hughen added. “Our approach offers the potential to unravel the role of climate in critical events of the recent fossil record, as it can be applied to any radiocarbon date from any deposit.”

Funding for Konrad Hughen’s research was provided by the National Science Foundation.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, independent organization in Falmouth, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment.