If you’ve ever plunged your head underwater and listened, you’ll know that sounds are muffled. But why? The reason is that your ears are adapted to hear in air, not water. Many marine animals do hear well underwater. For whales, crabs, and corals, detecting the sounds around them is a matter of survival.

Sound radiates through air or water in waves, like ripples on a pond. But it travels much more efficiently in water. It also travels faster, in part because water is denser than air. As the ocean gets deeper, the pressure increases water’s density, causing sound to travel even faster. In the ocean, variations in pressure can bend sound and make it hard to determine its source.

Whales are experts at detecting and deciphering sound in the ocean. They use sound for socializing, breeding, navigation, and feeding. The two main types of whales—baleen whales and toothed whales—use sound differently.

Baleen whales include humpback whales and blue whales. They communicate by making low-frequency sounds called songs, which can travel long distances.

Toothed whales, such as sperm whales and dolphins (known as odontocetes), have hearing that’s tuned to high-frequency sounds. They echolocate like bats, producing high-pitched clicks that bounce off elements in their environment. These echoes help them discern fish and other items in their surroundings.

Whales and dolphins (collectively known as cetaceans) have ears that are similar to ours, but with key differences. Humans have fleshy outer ears (called pinna) for capturing sounds, whereas cetaceans do not. Instead, dolphins have pads of fat along their lower jaws that collect sounds. These vibrations then travel into the labyrinth of the middle and inner ear to the cochlea, a snail-shaped organ that also exists in humans.

This organ transforms sound waves into electrical signals for the brain to process. Unlike humans, a dolphin’s cochlea contains far more nerve cells, reflecting the dolphin’s ability to process complex auditory signals. This allows odontocetes to hear much higher frequencies in the water. The cochlea of baleen whales, on the other hand, is more sensitive to low-frequency sounds.

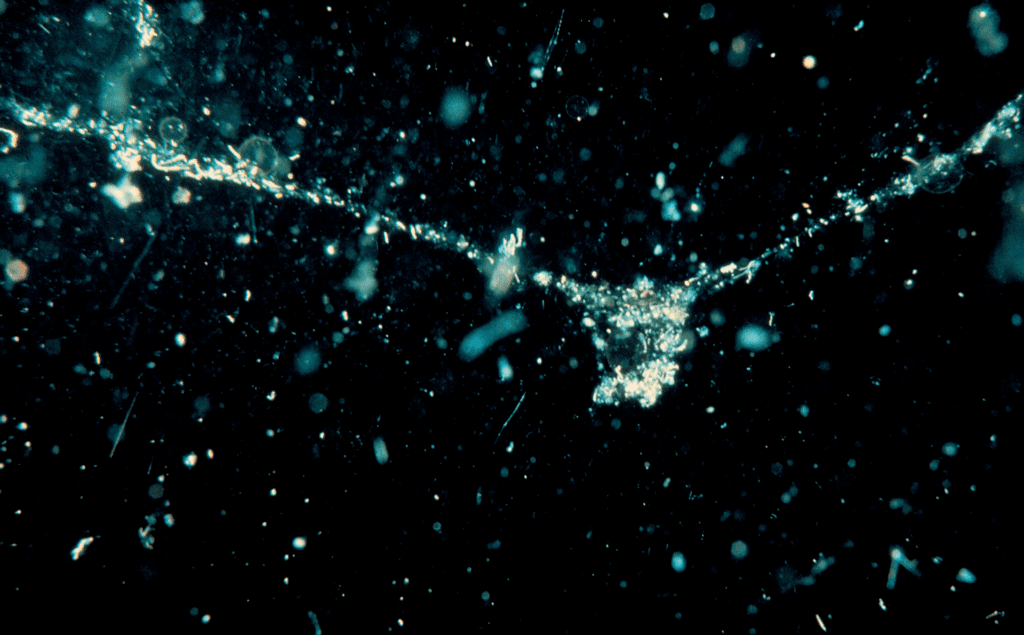

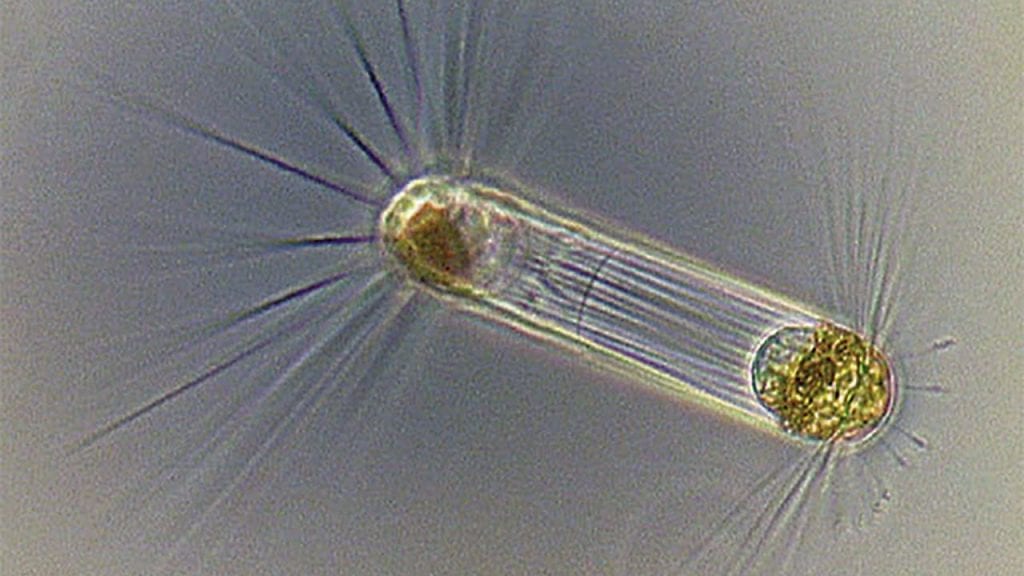

Corals, the animals that form the foundation of coral reefs, can also hear. These sessile animals reproduce by spawning, releasing sperm and eggs into the water, which mix to create larvae. A free-floating coral larva, roughly the size of a grain of sand, uses sound to select a spot where it will settle and spend its adult life. The larva is covered with microscopic, sound-sensitive hairs. A healthy reef is alive with the grunting and chirping of fish and the crackling of snapping shrimp. A damaged or dying reef is much quieter. Coral larvae can hear the difference. They are attracted to the sound of a healthy reef.

Crustaceans, like crabs and lobsters detect sound using thousands of microscopic hairs, called setae, which line their bodies. They also use internal fluid-filled sacs called statocysts, and stretch receptors located in the joints of their legs and antennae.

Like corals, crustaceans use sound to select a home. Some species live in coral reefs. Others avoid reefs, possibly to steer clear of predators. Sound helps guide these animals to a suitable home, either toward a reef or safely away.

LEARN MORE

Dr. Laela Sayigh

Studying cetacean behavior, this research explores communication, call structures, and human noise impacts using new technologies

Ocean Encounters: An Ocean of Sound

Learn how biologists are working to decipher animal communication, and use sound to protect ocean life and even restore degraded habitats

Dr. Aran Mooney

Studying the sensory biology of marine organisms and marine acoustic environments

Reef Solutions

Science and innovation to save coral reefs

Discovery of Sound in the Sea. Animals and Sound. https://dosits.org/animals/

Discovery of Sound in the Sea. How does sound in air differ from sound in water? https://dosits.org/science/sounds-in-the-sea/how-does-sound-in-air-differ-from-sound-in-water/

NOAA. Understanding Ocean Acoustics. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/sound01/background/acoustics/acoustics.html

Quaglia, Sofia. (2023) How Do Whales Hear Their Songs and Other Sounds if They Don’t Have Ears? Discover. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/how-do-whales-hear-their-songs-and-other-sounds-if-they-dont-have-ears

Radford, Craig A., & Stanley, Jenni A. (2023). Sound detection and production mechanisms in aquatic decapod and stomatopod crustaceans. Journal of Experimental Biology, 226(10).

WHOI. Coral Larvae Use Sound to Find a Home on the Reef. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/coral-larvae-use-sound-to-help-find-a-home-on-the-reef/

DIVE INTO MORE OCEAN FACTS

Where does all the carbon go?

Explore the ocean’s critical role in carbon sequestration and how it could be a pathway to mitigate climate change.

How do fish swim in schools?

Fish swim in schools to help them evade hungry predators, spot rich feeding areas, and find mates. But how do thousands of fish move together as fluidly as dancers?

Does the ocean produce oxygen?

It’s easy to think of the world’s forests as the planet’s “lungs.” Trees pump out oxygen—the same stuff we breathe in. But does all our breathable air come from just land?

How do polynyas help feed emperor penguins?

When female emperor penguins—and later, males—return to the ocean to feed, they need a spot that gives them easy access to both the water and the ice. And, they also need places that are teeming with fish and other types of prey. Learn how polynyas provide a place where penguins can feast and build their energy reserves after breeding.