Walrus Calves Stranded by Melting Sea Ice

April 13, 2006

Scientists have reported an unprecedented number of unaccompanied and possibly abandoned walrus calves in the Arctic Ocean, where melting sea ice may be forcing mothers to abandon their pups as the mothers follow the rapidly retreating ice edge north.

Nine lone walrus calves were reported swimming in deep waters far from shore by researchers aboard the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Healy during a cruise in the Canada Basin in the summer of 2004. Unable to forage for themselves, the calves were likely to drown or starve, the scientists said.

Lone walrus calves far from shore have not been described before, the researchers report in the April issue of Aquatic Mammals. The sightings suggest that increased polar warming may lead to decreases in the walrus population.

“We were on a station for 24 hours, and the calves would be swimming around us crying. We couldn’t rescue them,” said Carin Ashjian, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a member of the research team.

The researchers found evidence of warmer ocean temperatures that may have rapidly melted seasonal sea ice over the shallow continental shelf where walruses dive to feed on bottom-dwelling animals such as clams and crabs. Walrus need the ice to rest themselves and to leave the pups to rest while the mothers feed. Ice remained over very deep water.

“If walruses and other ice-associated marine mammals cannot adapt to caring for their young in shallow waters without sea-ice available as a resting platform between dives to the sea floor, a significant population decline of this species could occur,” the research team wrote. The lead author of the study is Lee W. Cooper, a biogeochemist at the University of Tennessee.

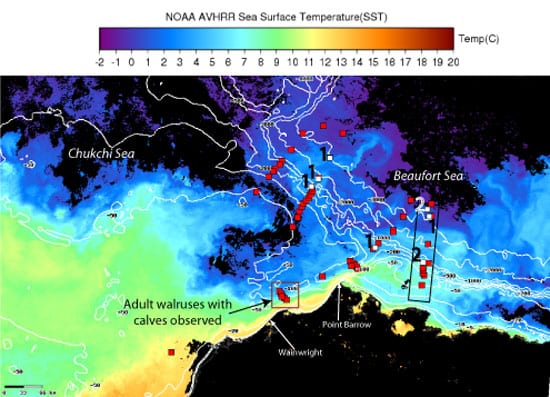

Cooper, Ashjian and other researchers made the unexpected walrus calf sightings during a cruise to investigate the impact of global climate change on the oceanic ecosystem over the continental shelf of Alaska. Their work focused on the shallower waters of the continental shelf in the Chukchi Sea to deeper waters in the Beaufort Sea of the Western Arctic Ocean. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research.

Adult Pacific walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens, forage for food by diving as far as 200 meters about (630 feet) down to the seafloor and using sensitive facial bristles to locate prey. Sea ice normally forms over the continental shelf north of Alaska and persists even in summer. Adult walrus use the sea ice as a resting platform; mothers leave the calves there and dive to the bottom for food.

“The young can’t forage for themselves,” Ashjian said. “They don’t know how to eat,” and are dependent on their mothers’ milk for up to two years.

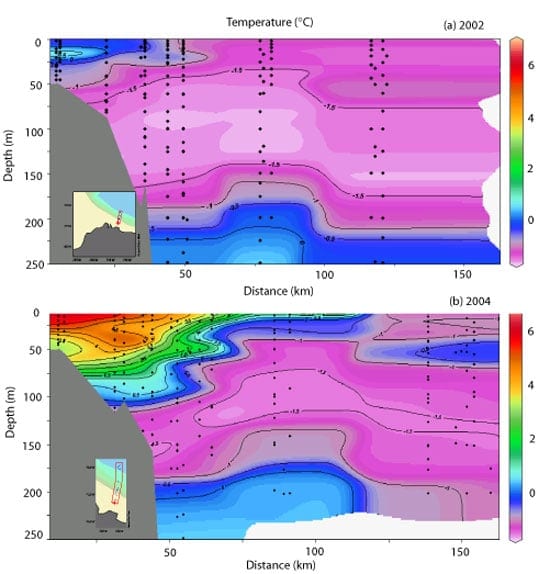

The researchers measured a mass of water as warm as 44°F (7°C) moving onto parts of the shelf from the Bering Sea to the south in 2004. This warm-water intrusion was more than six degrees higher than temperatures at the same time and location in 2002. The warmer water apparently caused seasonal sea ice to melt rapidly over the shallow continental shelf and retreat to deep water over the Arctic Ocean basins, where the water remained colder.

In the areas where ice remained, the bottom is up to 3,000 meters (about 9,300 feet) deep, too deep for even adult walrus to dive to feed. When sea ice retreats to such deep water, as it did in 2004, there are no platforms in shallow waters for mothers to rest and to leave their calves while they feed, and the pairs become separated.

Scientists on the Healy used geographic positioning, digital photography, ship bridge logs, and other observations to record the calves’ positions and bathymetric charts and depth sounder data to identify water depth. They documented the very warm water using both conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) profile sampling and plankton-net sampling, which revealed zooplankton species that prefer warmer waters.

In addition to Copper and Ashjian, other researchers participating in the study were Sharon L. Smith of the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Miami; Louis A. Codispoti of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science; Jaqueline M. Grebmeier of the University of Tennessee; Robert G. Campbell of the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography; and Evelyn B. Sherr of the College of Oceanographic and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University.