Scientists Discover Huge Phytoplankton Bloom in Ice Covered Waters

June 7, 2012

A team of researchers, including scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), discovered a massive bloom of phytoplankton beneath ice-covered Arctic waters. Until now, sea ice was thought to block sunlight and limit the growth of microscopic marine plants living under the ice.

The amount of phytoplankton growing in this under-ice bloom was four times greater than the amount found in neighboring ice-free waters. The bloom extended laterally more than 100 kilometers (62 miles) underneath the ice pack, where ocean and ice physics combined to create a phenomenon that scientists had never seen before.

The study, published June 8 in the journal Science, concluded that ice melting in summer forms pools of water that act like transient skylights and magnifying lenses. These pools focused sunlight through the ice and into waters above the continental shelf north of Alaska, where currents steer nutrient-rich deep waters up toward the surface. Phytoplankton under the ice were primed to take advantage of this narrow window of light and nutrients.

“Way more production is happening under the ice than we previously thought, in a manner that’s very different than we expected,” said WHOI biologist Sam Laney, who was part of the multi-institutional team led by Kevin Arrigo of Stanford University.

Just as a rainstorm in the desert can cause the landscape to explode with wildflowers, this research shows that events like pooling melt water can happen on very short timescales in the Arctic yet have major effects on the ecosystem.

“If you don’t catch these ephemeral events, you’re missing a big part of the picture,” Laney said.

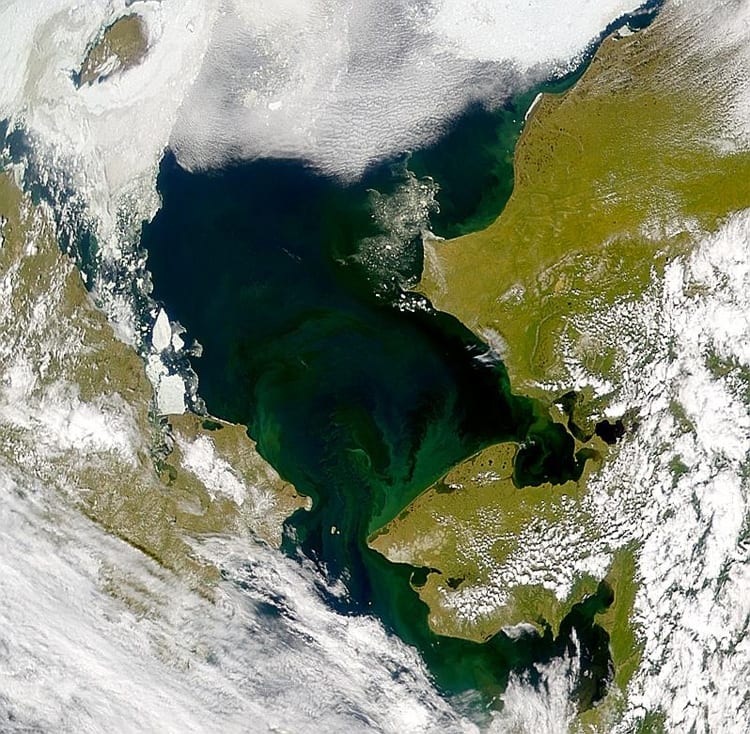

The unexpected discovery occurred during a 2011 expedition aboard the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Healy. It was part of the NASA-funded ICESCAPE program to investigate the impact of climate change in the polar Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

The scientists found themselves in the right place at the right time in early July of 2011, as the Healy made its way above the Arctic Circle and into year-old ice. Atop the meter-thick ice, pools of sky-blue melt water were accumulating as the Arctic summer progressed.

Researchers expected that, as in years past, the waters beneath the ice would have minimal amounts of chlorophyll—the fluorescing hallmark of photosynthetic marine plants. Instead, they observed the opposite. As the ship broke further into the ice, chlorophyll in the dark waters below shot up to levels rarely observed even in the most productive ocean regions. It became evident that there was a phytoplankton bloom of astonishing magnitude happening under the ice. Optical measurements showed that four times as much light penetrated ice covered by meltwater ponds than ice covered by snow.

“Although the under-ice light field was less intense than in ice-free waters, it was sufficient to support the blooms of under-ice phytoplankton, which grew twice as fast at low light as their open ocean counterparts,” the study notes.

The ship conducted transects into the ice pack to determine how far and deep the bloom extended. Measurements of biomass showed the largest part of the bloom occurred far away from the open ocean, under thick ice and close to water upwelling at the continental shelf break, where the shallow coastal shelf plunges steeply into deeper water.

Another member of the ICESCAPE team, WHOI physical oceanographer Bob Pickart showed that easterly winds churned out by monster storm systems along the Aleutian Islands can reverse the current along the shelf break. The change in circulation drives cold, nutrient-rich water up from the abyss and refreshes the supply of nutrients available to phytoplankton growing near the surface.

“Without a doubt the bloom was enhanced at the shelf break,” Pickart said.

As the melt pools introduced light through the ice, phytoplankton in shelf break waters likely experienced something akin to an all-you-can-eat buffet.

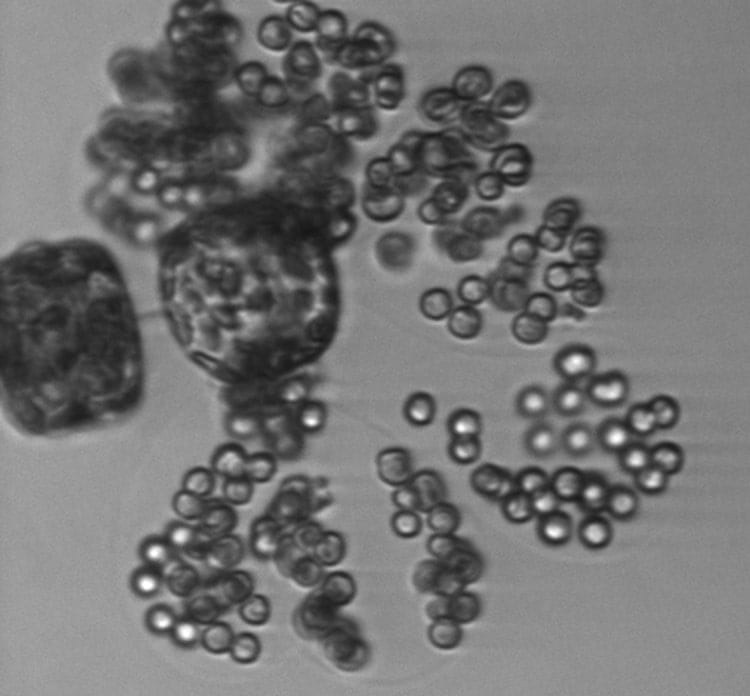

What types of organisms participated in the bloom? Laney caught them on camera with an instrument he had brought to sea—the Imaging FlowCytobot, an automated microscopic imaging system invented at WHOI and built by Laney and co-developer Dr. Rob Olson.

Since their return, Laney and MIT/WHOI Joint Program graduate student Emily Brownlee have been working with the Imaging FlowCytobot’s other co-developer and ICESCAPE team member, WHOI biologist Heidi Sosik, to sort through and classify organisms in the millions of images collected by the instrument and unravel intricacies of the under-ice bloom. The images showed that the bloom was not caused by fallout from algae growing on the ice, but rather it contained different organisms that seized the confluence of currents, light, and nutrients.

The Imaging FlowCytobot offers tantalizing insights into the microbial dynamics and food web of this dramatic Arctic algal boom. For example, the images consistently showed some phytoplankton in the bloom in a half-munched state, offering clues to the planktonic grazers that might be eating them.

Discovering the under-ice bloom “was very serendipitous,” Pickart said, but the difficulty of exploring the harsh, remote region also leaves it wide open for surprises.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans’ role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.