New Whale Detection Buoys Will Help Ships Take the Right Way through Marine Habitat

April 29, 2008

Researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Bioacoustics Research Program (BRP) at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have teamed up with an international energy company and federal regulators to listen for and help protect endangered North Atlantic right whales in New England waters.

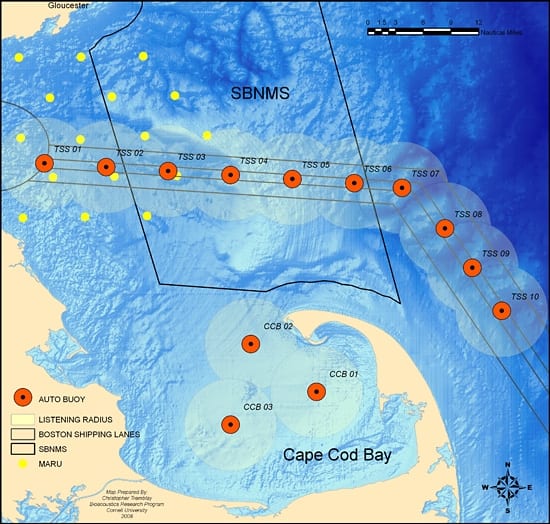

Building on advances in ocean mooring design, underwater acoustic systems, and telecommunications, the team built and installed ten “auto-detection buoys” to listen for the calls of right whales along the main shipping lanes into Massachusetts Bay and Boston Harbor.

The array of instruments—conceived by biologist and engineer Christopher W. Clark of the Cornell Lab and engineer John Kemp of WHOI was largely funded by Excelerate Energy, L.L.C., as part of its environmental compliance associated with its Northeast Gateway deepwater port for liquefied natural gas (LNG). The import facility is set to begin operations in spring 2008.

The new listening system allows researchers to detect the location of whales in real time and alert ship operators and coastal resource managers to their presence. With advance warning, ships can be slowed or re-routed to prevent collisions, which is the most common cause of death for the iconic New England whale.

Marine biologists estimate that only 350 to 400 right whales remain in the North Atlantic.

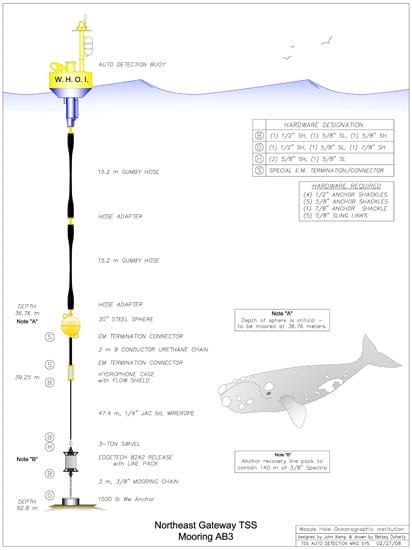

“North Atlantic right whales migrate through a highly industrialized part of the coastline, and we need creative solutions to help them survive,” said Kemp, an engineer in WHOI’s Department of Applied Ocean Physics and Engineering. “The challenge was to develop a mooring that could stand up to the stresses of harsh New England waters while keeping an acoustically quiet environment for the hydrophones.”

Mandated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the whale-detection system was installed along a 55 nautical mile segment of the Boston Traffic Separation Scheme (primary shipping lanes) leading to Boston Harbor.

The Northeast Gateway is located approximately 13 nautical miles south southeast of Gloucester, Mass., and 1.8 nautical miles from the western border of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (which is managed by NOAA).

Since the route to the LNG terminal takes vessels through prime whale habitat, researchers and regulators from the sanctuary and NOAA Fisheries worked with the Port’s licensing agencies (the US Coast Guard and the Maritime Administration) and Excelerate Energy to develop a plan to keep whales and LNG ships out of each other’s way in Massachusetts Bay.

Excelerate Energy then entered into a partnership with the Cornell Lab and WHOI to develop the remote auto-detection system. To further reduce the operational risk of ship strikes, Excelerate Energy has trained its crew members to watch for marine mammals and sea turtles as their vessels travel to and from the port.

Each auto-detection buoy is instrumented with an underwater microphone—or hydrophone—to carry underwater sounds to the surface via specially designed cable that WHOI technicians playfully call it the “Gumby hose.” The stretchy, hose-like cable has data-conducting wires woven into its walls.

More importantly, the Gumby hose can stretch to at least twice its normal length, a special mooring design created at WHOI to overcome harsh sea states and keep the buoy above water. In typical winter storm conditions in the North Atlantic, wave heights in coastal waters can swell to 10 meters (33 feet), putting dangerous strain on traditional mooring lines and creating excessive noise that would make whale detection nearly impossible.

Data from the hydrophones are relayed through the Gumby hose to customized computers on the surface buoy, which continuously analyze underwater sounds to detect possible right whale calls. Every 20 minutes, these acoustic detections are sent by cellular or satellite phone to a server at Clark’s lab, where they are validated by whale call experts.

In the process, researchers can determine whether right whales have been detected within range of each buoy and then alert Excelerate Energy and, perhaps eventually, other ships using maritime telecommunications networks.

“Thanks to these efforts, for the first time, ship captains can receive continuous information on where the whales are so they can slow down and avoid tragic collisions,” said Clark, lead scientist on the project. “Scientific studies indicate that the death of just one or two breeding females a year will lead to the population’s extinction. Slowing down for whales will make a big difference.”

The WHOI Mooring Operations, Engineering, and Field Support Group has been designing, building, and deploying scientific instruments in the sea for decades, making dozens of installations around the world each year for researchers from WHOI and many other institutions and companies.

Kemp and Clark have been working together on the whale-detection system since 2003, testing several different hydrophones and mooring designs. The team recently deployed three whale detection buoys in Cape Cod Bay for the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and two off the coasts of Georgia and Florida.

The effort to detect and protect whales in Massachusetts Bay is part of a larger effort by scientists and personnel from the New England Aquarium, Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies, NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, WHOI, and other members of the Right Whale Consortium.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, independent organization in Falmouth, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans’ role in the changing global environment.