Effects of Ocean Fertilization with Iron To Remove Carbon Dioxide from the Atmosphere Reported

April 16, 2004

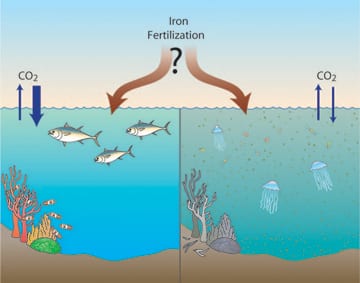

Dumping iron in the ocean is known to spur the growth of plankton that remove carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere, but a new study indicates iron fertilization may not be the quick fix to climate problems that some had hoped.

Scientists have quantified the transport of carbon from surface waters to the deep ocean in response to fertilizing the ocean with iron, an essential nutrient for marine plants, or phytoplankton. Prior work suggested that in some ocean regions, marine phytoplankton grow faster with the addition of iron, thus taking up more carbon dioxide. However, until now, no one has been able to accurately quantify how much of the carbon in these plants is removed to the deep ocean.

New data, reported in the April 16 issue of the journal Science, suggest that there is a direct link between iron fertilization and enhanced carbon flux and hence atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, but that the quantities that can be removed are no greater than natural plankton blooms and are not large enough to serve as a quick fix to our climate problems.

Results from the largest ocean fertilization experiment to date, the Southern Ocean Iron Experiment (SOFeX), are reported in three related articles in Science. Ken Buesseler and coauthors John Andrews, Steven Pike and Matthew Charette of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department reported their findings on ocean carbon fluxes in one of the articles, and Buesseler is a coauthor on a second article.

SOFeX was conducted using three ships in January and February 2002 at two sites in the Southern Ocean, the oceans surrounding Antarctica. More than 100 scientists were involved with the international, US-led effort, funded by the National Science Foundation with additional support from the Department of Energy.

The 2002 study focused on two areas of 15 square kilometers (about 10 square miles) in the Southern Ocean between Antarctica and New Zealand. The sites were chosen to represent contrasting ecological and chemical conditions in the Southern Ocean. Just over one metric ton (2,200 pounds) of iron was added to surface waters to stimulate biological growth at the southern site that Buesseler studied. Scientists aboard the three ships observed the biological patch for 28 days and measured the amount of carbon being transported deeper into the ocean in the form of sinking particulate organic carbon.

Buesseler and colleagues quantified for the first time how much carbon was being removed in response to iron from surface waters to depths of 100 meters (about 300 feet), which they estimated at 1,800 tons (about 4 million pounds) for an area of 400 square miles. They were surprised to find that particles were being carried to the deep sea more efficiently in response to the addition of iron, but noted that this carbon flux is still quite low compared to natural variations at these latitudes.

The controversial idea of fertilizing the ocean with iron to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere gained momentum in the 1980s. Climate and ocean scientists, as well as ocean entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, saw potential for a low-cost method for reducing greenhouse gases and possibly enhancing fisheries . Plankton take up carbon in surface waters during photosynthesis, creating a bloom that other animals feed upon. Carbon from the plankton is integrated into the waste products from these animals and other particles, and settles to the seafloor as “marine snow” in a process called the “biological pump.” Iron added to the ocean surface increases the plankton production, so in theory fertilizing the ocean with iron would mean more carbon would be removed from surface waters to the deep ocean. Once in the deep ocean, the carbon would be “sequestered” or isolated in deep waters for centuries. The oceans already remove about one third of the carbon dioxide released each year due to human activities, so enhancing this ocean sink could in theory help control atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and thus regulate climate.

Three previous open-ocean fertilization experiments have been conducted in the Southern Ocean. The 13-day Southern Ocean Iron Enrichment Experiment (SOIREE) in 1999, the 21-day Eisen or Iron Experiment (EisenEx-1) in 2000 and the 2002 Southern Ocean Iron Experiment (SOFeX) all produced significant increases in planktonic biomass and decreases in dissolved inorganic carbon in the water column. Last month, a European group returned from EIFEX (European Iron Fertilization Experiment), another iron fertilization experiment in the Southern Ocean.

However, there was limited evidence until now that the particles carried significant quantities of carbon to the deep ocean.

Buesseler participated in several of these experiments, and studies thorium, a naturally occurring element that is “sticky” by nature and serves as an easy-to-measure proxy for carbon export in seawater. Recent thorium experiments show that many factors affect carbon uptake by plankton in surface waters. For example, biological communities and plankton production vary with location and season, so the balance between carbon uptake by the marine plants and carbon export on sinking particles is highly variable and typically only a few percent of the carbon sinks to the deep ocean.

Buesseler and his colleagues say that simply adding iron to the ocean may not result in enhanced removal of carbon dioxide from surface waters to the deep ocean. “You would have to keep doing it over, and if you wanted to have a big impact the size of the area required is bigger than the Southern Ocean. And even if you could do it, what effect might it have on other aspects of ocean ecology? This remains an unknown.”

WHOI is a private, independent marine research and engineering, and higher education organization located in Falmouth, MA. Its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, the Institution is organized into five scientific departments, interdisciplinary research institutes and a marine policy center, and conducts a joint graduate education program with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.