A new underwater robot could help preserve New England’s historic shipwrecks

WHOI’s ResQ ROV to clean up debris in prominent marine heritage sites

From ruin to reef

What Pacific wrecks are teaching us about coral resilience—and pollution

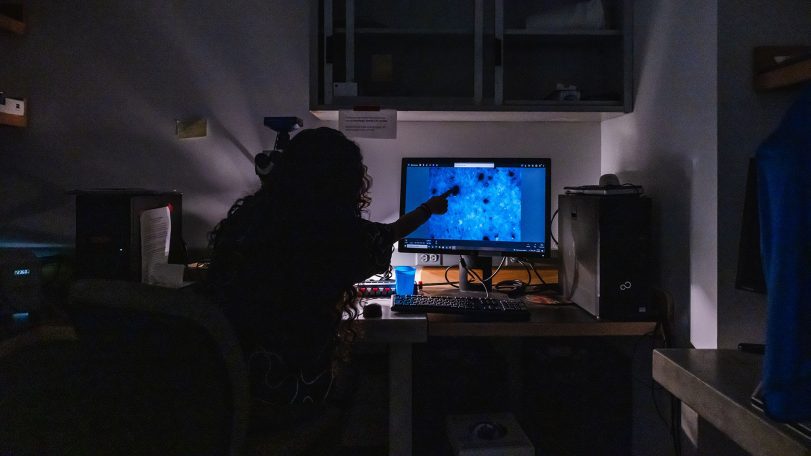

One researcher, 15,000 whistles: Inside the effort to decode dolphin communication

Scientists at WHOI analyze thousands of dolphin whistles to explore whether some sounds may function like words

Remembering Tatiana Schlossberg, a voice for the ocean

Environmental journalist and author Tatiana Schlossberg passed away after battling leukemia on December…

As the ocean warms, a science writer looks for coral solutions

Scientist-turned-author Juli Berwald highlights conservation projects to restore coral reefs

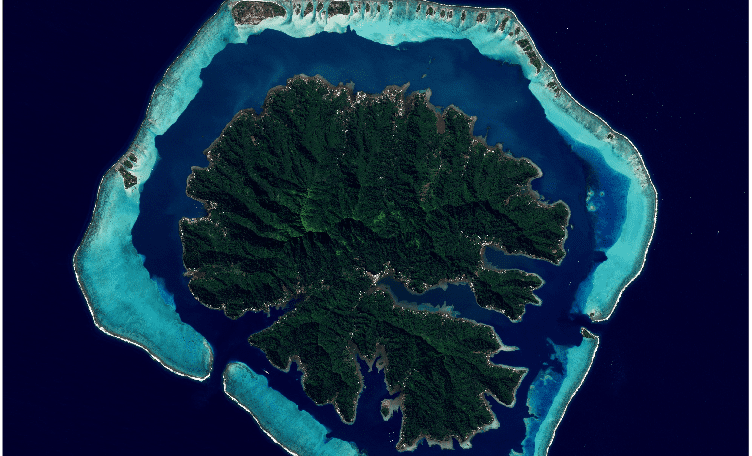

How an MIT-WHOI student used Google Earth to uncover a river–coral reef connection

Google Earth helps researcher decode how rivers sculpt massive breaks in coral reefs

The little big picture

WHOI senior biologist Heidi Sosik on the critical need for long-term ocean datasets

Lessons from a lifetime of exploration

Award-winning ocean photographer Brian Skerry shares insights from a career spent around ocean life and science

and get Oceanus delivered to your door twice a year as well as supporting WHOI's mission to further ocean science.

Our Ocean. Our Planet. Our Future.

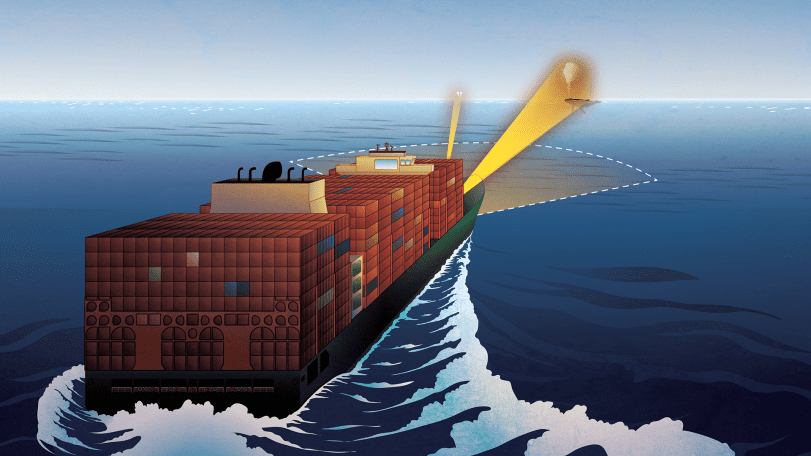

The ocean weather nexus, explained

The vital role of ocean observations in extreme weather forecasting

Breaking down plastics together

Through a surprising and successful partnership, WHOI and Eastman scientists are reinventing what we throw away

Three questions with Carl Hartsfield

Captain Hartsfield, USN retired, discusses the role ocean science plays in our national defense

The Ocean (Re)Imagined

How expanding our view of the ocean can unlock new possibilities for life

Body snatchers are on the hunt for mud crabs

WHOI biologist Carolyn Tepolt discusses the biological arms race between a parasite and its host

A polar stethoscope

Could the sounds of Antarctica’s ice be a new bellwether for ecosystem health in the South Pole?

Secrets from the blue mud

Microbes survive—and thrive—in caustic fluids venting from the seafloor

Looking for something specific?

We can help you with that. Check out our extensive conglomeration of ocean information.

Top 5 ocean hitchhikers

As humans traveled and traded across the globe, they became unwitting taxis to marine colonizers

Following the Polar Code

Crew of R/V Neil Armstrong renew their commitment to Arctic science with advanced polar training

Harnessing the ocean to power transportation

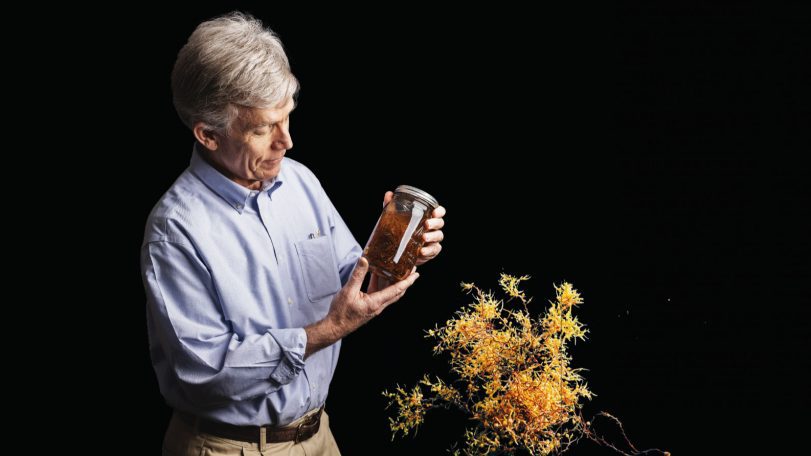

WHOI scientists are part of a team working to turn seaweed into biofuel

Casting a wider net

The future of a time-honored fishing tradition in Vietnam, through the eyes of award-winning photographer Thien Nguyen Noc

Gold mining’s toxic legacy

Mercury pollution in Colombia’s Amazon threatens the Indigenous way of life

How do you solve a problem like Sargassum?

An important yet prolific seaweed with massive blooms worries scientists

Ancient seas, future insights

WHOI scientists study the paleo record to understand how the ocean will look in a warmer climate

Rising tides, resilient spirits

As surrounding seas surge, a coastal village prepares for what lies ahead

Whistle! Chirp! Squeak! What does it mean?

Avatar Alliance Foundation donation helps WHOI researcher decode dolphin communication

The Big MELT

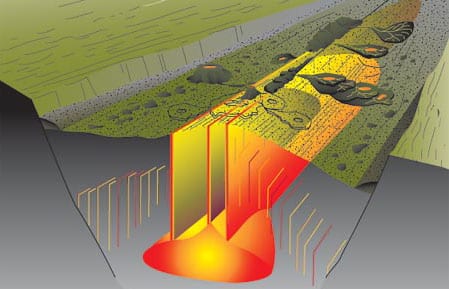

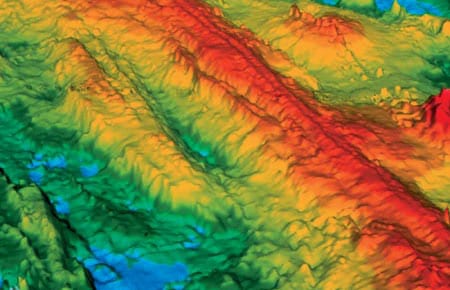

More than 95 percent of the earth’s volcanic magma is generated beneath the seafloor at mid-ocean ridges.

Mid-Atlantic Ridge Volcanic Processes

Long before the plate-tectonic revolution began in the 1960s, scientists envisioned drilling into the ocean crust to investigate Earth’s evolution.

Indian Ocean’s Atlantis Bank Yields Deep-Earth Insight

I never imagined I would spend six weeks of my life “wandering around” the seafloor exploring an 11 million year old beach, and it never occurred to me to look for a fossil island. But that’s what I did, and that’s what we found on two research voyages separated by more than a decade.

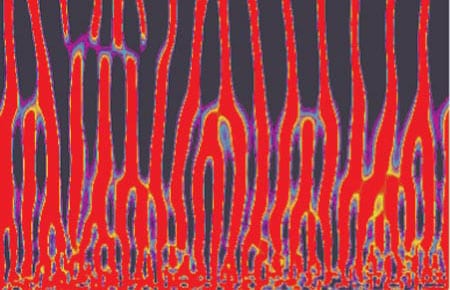

Melt Extraction from the Mantle Beneath Mid-Ocean Ridges

As the oceanic plates move apart at mid-ocean ridges, rocks from Earth’s mantle, far below, rise to fill the void, mostly via slow plastic flow.

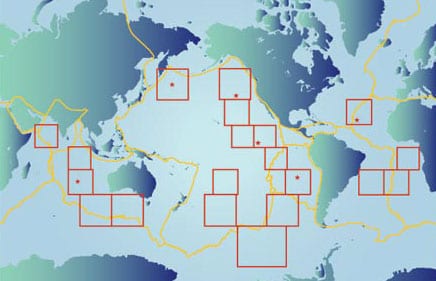

Exploring The Global Mid-Ocean Ridge

There is a natural tendency in scientific investigations for increased specialization. Most important advances are made by narrowing focus and building on the broad foundation of earlier, more general research.

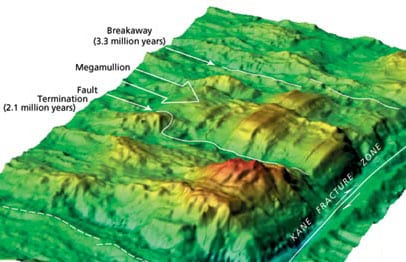

Discovery of “Megamullions” Reveals Gateways Into the Ocean Crust and Upper Mantle

urposes. From the end of the nineteenth into the first half of the twentieth century, drilling was used to penetrate the reef and uppermost volcanic foundation of several oceanic islands, and these glimpses of oceanic geology whetted the scientific community’s appetite for deeper and more complete data.

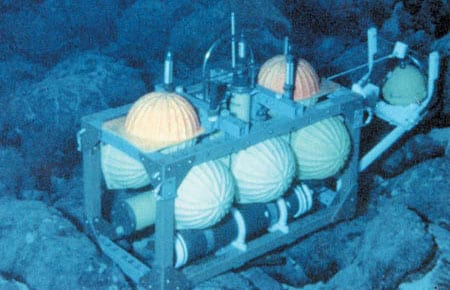

Ocean Seismic Network Seafloor Observatories

Our knowledge of the physical characteristics of Earth’s deep interior is based largely on observations of surface vibrations that occur after large earthquakes. Using the same techniques as CAT (Computer Aided Tomography) scans in medical imaging, seismologists can “image” the interior of our planet. But just as medical imaging requires sensors that surround the patient, seismic imaging requires sensors surrounding the earth.

The Women of FAMOUS

My FAMOUS story begins during my first year in graduate school at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia.

A Current Affair

oal of probing the earth’s inaccessible deep interior. But the technique remains something of a mystery even to many marine scientists. It has been used widely on land, particularly for regional-scale surveys, but only a few full-scale MT surveys have been carried out on the seafloor.

The Oceanic Flux Program

The predawn hours at sea have a unique feel—an eerie stillness, regardless of weather. This morning is no exception as the Bermuda Biological Station’s R/V Weatherbird II approaches the OFP (Oceanic Flux Program) sediment trap mooring some 75 kilometers southeast of Bermuda.

Marine Snow and Fecal Pellets

Until about 130 years ago, scholars believed that no life could exist in the deep ocean. The abyss was simply too dark and cold to sustain life. The discovery of many animals living in the abyssal environment by Sir Charles Wyville Thompson during HMS Challenger’s 1872-1876 circumnavigation stunned the late 19th century scientific community far more than we can now imagine.

Extreme Trapping

One of oceanography’s major challenges is collection of data from extraordinarily difficult environments. For those who use sediments traps, two examples of difficult environments are the deepest oceans and the permanently ice-covered Arctic Basin.