Where Will We Get Our Seafood?

Unlike the rest of the world, the U.S. has not embraced aquaculture

By 2030 or 2040, most seafood bought by Americans will be raised on a farm, not caught by fishermen. And, unless policies governing aquaculture in the United States change, the vast majority of seafood eaten by Americans will be farm-raised in another country, possibly one with less stringent health and environmental regulations.

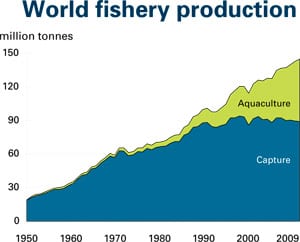

With wild fisheries in decline, the world has turned to aquaculture to provide protein to feed Earth’s rapidly growing human population. But not the United States. While aquaculture already produces half of the world’s seafood, U.S. aquaculture production has been declining since 2003 and today, the U.S. produces only 10 percent of its seafood by aquaculture, said Hauke Kite-Powell, an aquaculture policy specialist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). One consequence of this is that the U.S. imports 80 percent of the seafood it consumes, creating a seafood trade deficit.

The U.S. could provide most of the seafood its population needs via aquaculture, he said, but a host of economic, environmental, health, and policy issues has muddied the waters. The fishing industry has economic concerns about retaining jobs in traditional commercial fishing; and there are uncertainties about regulations governing aquaculture, especially in federal waters. And while conservationists fight to protect overfished fisheries and endangered species, they also have ecological concerns about fish farms and about antibiotics, chemicals, and feeds used to raise fish.

“For a number of years, bills have been introduced in Congress to set up a streamlined permitting mechanism to facilitate aquaculture in federal waters, but those bills have never gone anywhere, mainly because of opposition from fishing communities and environmental groups,” Kite-Powell said. “Seafood consumption is rising more quickly abroad than it is here in the United States. Should we take active steps to prepare for a future when international supplies may not be as readily available as they currently are?”

To explore these issues, Kite-Powell gathered scientists and representatives from the seafood industry, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the United Nations, and conservation groups to a two-day colloquium at WHOI in May 2011. This was the seventh Morss Colloquium—meetings that bring experts to WHOI to exchange and foster ideas on important issues that confront human society today. The colloquia are supported by a generous donation from Elisabeth and Henry Morss.

Kite-Powell elaborated on these issues in an interview.

What do you hope people take away from this colloquium?

Kite-Powell: The main thing is that we can do things to increase seafood production in the U.S. that are ecologically and economically sound, and that seafood and fishing industries and the environmental community can find common ground on this issue. It’s not a black-or-white situation where all seafood farming is environmentally harmful. If it’s done right, it’s a good thing. And whether we like it or not, aquaculture will become more and more important in the future. There’s just no getting away from that.

Why did you bring this group together for a colloquium?

Kite-Powell: The main motivation for me was the stalemate in the U.S. over aquaculture in federal waters. It’s a question of thinking about future international competition for food production resources. We’re starting to hear a lot about impending fresh water constraints in many parts of the world, and the limits of the productivity of land-based agricultural resources. Seafood is likely to play a more important role in global protein supply in the future than it does today.

People here in New England like the quaint lobster boat, and there’s nothing wrong with artisanal fisheries. In many places around the world, they’re a key piece of the local social fabric. But that’s not where the solution to our food supply problems is going to come from.

Could we as a country meet all our domestic seafood needs with aquaculture?

Kite-Powell: There’s no ecological or environmental reason why we couldn’t match our consumption with production.

What stands in the way?

Kite-Powell: There needs to be a meeting of minds among fish farmers and the people who have concerns about expanded seafood farming, and that’s starting to happen. Environmental groups are starting to describe approaches to seafood farming that they consider acceptable, and there’s a growing recognition that farmed seafood is here to stay.

Do you think the growth of fish aquaculture is bad for the fishing industry or for environmental groups?

Kite-Powell: No, I don’t. Wild fisheries are exploited so heavily today that there really isn’t room for more production or economic value from “capture fisheries.” So if we want to increase employment in the seafood industry and increase the whole fisheries value chain in the U.S., it will have to come from farmed seafood. Many environmental groups understand the value of seafood in the human diet, and there’s a strong argument for farming seafood in a sustainable way.

We had fishermen at our meeting comment on this. They see their future and the future of their colleagues as being a mix of wild-capture fishing, maybe six months out of the year, and fish farming the other six months, probably shifting more to farming over time. Historically, that’s how it’s gone with land-based food production.

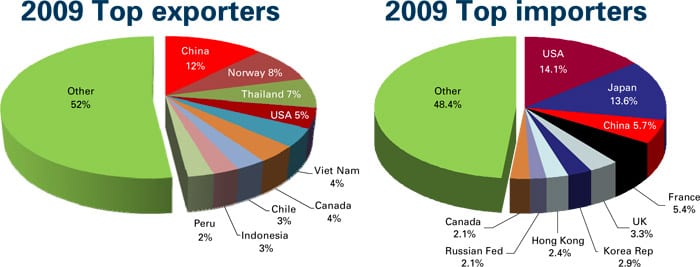

What conclusions did you reach about the U.S. seafood trade deficit?

Kite-Powell: Two key facts were highlighted in the colloquium discussions. First, the U.S. seafood trade deficit is important to the seafood industry, but it’s not a big contributor to our national trade picture—it’s swamped by our trade in petroleum and manufactured goods. So eliminating the seafood trade deficit is not going to make a noticeable dent in our nation’s overall trade situation.

And second, trade in seafood is not necessarily a bad thing. If there are other countries that can produce high-quality seafood much more efficiently than we can, it makes sense for us to buy it from them. There are species that we may not want to grow in large quantities in the U.S.—possibly shrimp, which comprises a big chunk of our seafood trade deficit. Shrimp are farmed most efficiently in coastal ponds, and we don’t have a lot of spare coastal real estate for ponds in the U.S. So it may not make sense to try to become self-sufficient in shrimp.

You suggest it would be better for the environment if the world meets growing protein needs by increasing aquaculture, even if it takes some coastal or land areas.

Kite-Powell: I think that’s right. Based on the numbers that were presented at our meeting, it is ecologically more efficient to produce fish in a farm than it is in the wild. It’s also less energy-intensive and less carbon-intensive to get protein from fish than beef and other four-legged animals. Fish are equivalent to poultry in those terms.

But it has to be done in a way that doesn’t create excessive side effects. And just like in agriculture, we know how to do it right, and we know how to do it wrong, and we can make those decisions.

Does the U.S. have to worry about other nations “doing it wrong” when it comes to aquaculture, in terms of public health and environmental damage?

Kite-Powell: If we rely on food farmed in other places, that’s not necessarily a problem, but it requires us to have partnerships with, or presence in, other producing countries to ensure that the food consistently meets the standards we would like to see. Growing it here requires supervision , too, but regulations are largely in place in the U.S. already.

Will wild fish become a specialty item?

Kite-Powell: Yes, probably. To some degree, that’s already happened. You see wild-caught salmon marketed as “wild-caught,” and people distinguish it from farmed fish. We have similar distinctions in marketing with meat and poultry.

Some people can afford to pay more for something that is closer to wild. But given our global population situation, most people can’t.

Some people think there’s a taste difference between farmed and wild seafood, for instance, salmon.

Kite-Powell: Yes, I think that’s true, in the same way a Butterball turkey tastes different from a wild turkey. The food constituents that go into them are different. Wild salmon eat a lot of little crustaceans, and that’s not in the feed given to farm-bred salmon. But lots of people like eating farmed salmon (and turkeys). And there will be continuing innovation in feed, in order to produce a product that people like. The real technological key will be finding substitute sources for the food for finfish—other than fish meal and fish oil, which are now made from wild fish like anchovetta.

Will stocks of those feed fishes be depleted?

Kite-Powell: Most of those fish stocks are managed reasonably well—because they’re economically quite valuable to the countries that fish them. So that’s not at the top of my list of things to worry about.

What is at the top?

Kite-Powell: That’s a good question. In many places in the world overfishing is still rampant because growing populations are leaning much too hard on a fragile resource through artisanal fisheries, such as I’ve seen in Africa. It’s really urgent to bring fish farming approaches that are suited to those environments, and are ecologically sound, to the places where people really need more seafood protein—not just because they like it, but because they really need it.

The Economic Implications and the Role of U.S .Aquaculture in Future U.S. Seafood Supply workshop and colloquium was funded by the Elisabeth W. and Henry A. Morss, Jr., Colloquia Endowed Fund at WHOI.

Slideshow

Slideshow

A salmon rose, part of a sashimi dinner set. More than 80 percent of the seafood eaten in the U.S. is imported, and most of the imported seafood is farmed.

((Wiki Commons))- World fishery production from 1950 to 2009. Wild fisheries are declining, as 80 percent of assessed fish species are fully or over-exploited, while aquaculture is increasing globally as a source of seafood production, according to the United Nations Food and Aquaculture Organization. (Stefania Vannuccini, Fishery Statistician, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Statistics and Information Service)

- The top seafood importers and exporters by dollar value in 2009, from United Nations Food and Aquaculture Organization statistics. U.S. seafood exports make up 5 percent of the global market value, while seafood imports account for more than 14 percent of the total value of global seafood trade, creating a significant seafood trade deficit for the U.S. ("Other" indicates many nations with very small import or export amounts.) (Stefania Vannuccini, Fishery Statistician, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Statistics and Information Service)

- Women on the island of Zanzibar, off Tanzania, set up a shellfish farm in 2006 after working with Hauke Kite-Powell, research specialist in the WHOI Marine Policy Center. Kite-Powell is working with fishing communities, scientists, and nonprofit groups to promote aquaculture as an ecologically sound way to increase seafood yield for human consumption, provide jobs, and produce a saleable product. (Photo by Hauke Kite-Powell, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- In May 2011, marine policy specialist Hauke Kite-Powell brought together a broad group of aquaculture experts for a WHOI-funded Morss Colloquium to discuss global seafood consumption trends and the future of aquaculture. Kite-Powell (at podium) and other experts gave public presentations on the issues facing U.S. aquaculture. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- Puzzling over a mollusk mystery

- An ocean of opportunity

- Can Clams and Oysters Help Clean Up Waterways?

- Jet Fuel from Algae?

- Farming Shellfish in Zanzibar

- New Regulations Proposed for Offshore Fish Farms

- Should Eastern Oysters Be Put on the Endangered List?

- A Mysterious Disease Is Infecting Northeast Clam Beds

- A Whole New Kettle of Fish

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Hauke Kite-Powell

- "The Seafood Dilemma" Colloquium

- Aquaculture WHOI Ocean Topic

- Farming Shellfish in Zanzibar Video from Oceanus magazine

- Down on the Farm...Raising Fish An article on aquaculture by Hauke Kite-Powell from Oceanus magazine

- Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- About Morss Colloquia

- Fisheries and aquaculture research sponsored by Woods Hole Sea Grant