To Catch a Hurricane

Makeshift devices collect sand transported by storm

On Aug. 25, 2011, the line projecting Hurricane Irene’s path up the East Coast barreled smack into Woods Hole, Mass., spurring a whirlwind in Jeff Donnelly’s lab at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). Scientists and students hustled to create a network of instruments that would capture a hurricane in action. They scurried to get their supplies: 100 bottles of soda pop and a few dozen pairs of ladies’ nylon stockings.

Donnelly is a coastal geologist who uncovers long-term records of past hurricane activity. His evidence is sand transported by hurricane winds and waves into quiescent lagoons and shoreline ponds. The sand settles in layers at the bottom and is buried by black, organic-rich mud that ordinarily sifts down in non-hurricane conditions.

The lab group cores into these bottom sediments to extract a slice of a region’s hurricane history, going further back in time as they dig deeper. Over decades and centuries, telltale hurricane layers, interspersed with organic mud, stand out like lines in a bar code. Radiocarbon dating of material in the layers reveals when the hurricanes occurred.

“We wanted to record how sediment is transported in an actual event—a modern analog we could compare with past records,” said Andrea Hawkes, a postdoctoral investigator at WHOI. “The idea of a hurricane hitting here was not appealing, but scientifically, it was very appealing.”

“We were sitting in a pub saying, ‘What can we do to increase our understanding of sediments mobilized by hurricanes?’ ” said Pete van Hengstum, a postdoctoral fellow at WHOI from Canada. “Over a pint, we hatched a plan with two components. First, we would capture the sand as it was being transported off the beach barrier by wind and water; and second, we would catch the sand once it got thrown into the ponds.”

With Irene only a few days away, the researchers received a small rapid-response grant from the WHOI Coastal Ocean Institute. Hawkes and a cadre of lab technicians and summer students hurriedly fashioned their instruments. They cut small sections of clear plastic tubes. Onto each, they fitted an ankle-length nylon stocking with a hose clamp. The tubes would funnel sand into the socks.

“We did a few quick tests in the lab on the tensile strength of the socks and determined that water would go through, but fine sand wouldn’t, and that the socks wouldn’t tear if filled or in surging water,” Hawkes said.

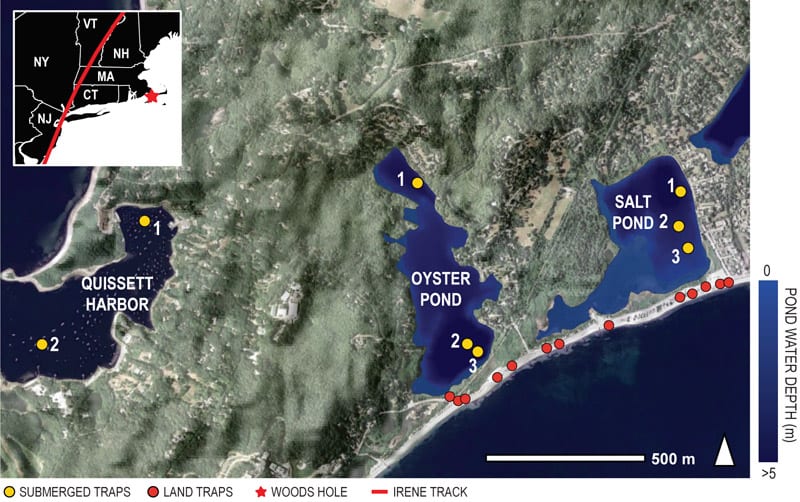

Then they took to the field, screwing 30 of their sand-catchers to utility poles, signs, and even a piling on a beach house (with permission from the owner) along Surf Drive in Woods Hole. The road runs along a thin barrier beach that fronts Oyster Pond and Salt Pond.

Meanwhile, van Hengstum, lab technicians, and students hastened to construct his marine instruments. “We bought 100 2-liter bottles of a no-name brand of soda at 99 cents a bottle,” he said. “We tried to get used bottles, but they are shredded at recycling centers. So we put a lot of soda down the drain.”

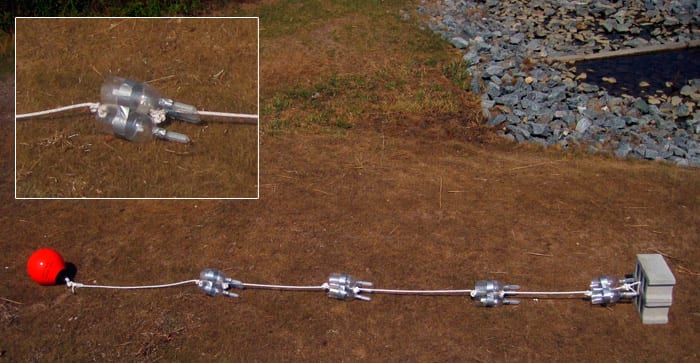

They cut off the bottoms and secured 50-milliliter plastic centrifuge tubes into the bottles’ mouths with duct tape. They attached three of their apparatus open side-up along a rope, spaced 1 to 2 meters apart with knots, and tied a cinder-block anchor to the bottom of the line and a float to the top. With winds signaling Irene’s imminent approach, van Hengstum and colleagues used a boat to submerge 30 instruments in Oyster and Salt Ponds, Quissett Harbor, and Waquoit Bay.

After hustling for three days, the team was ready when Irene arrived in Woods Hole on Aug. 28. But by then it had weakened to a tropical storm with winds slightly under the 74 mile-per-hour threshold for a Category 1 hurricane.

After the storm, the team quickly retrieved their socks and pop bottles. They got more than a few looks and curious questions from passersby who wondered about the bevy of sock contraptions that had sprouted in the neighborhood, Hawkes said. The impromptu sand-catchers successfully collected the required data.

“We wanted to get a baseline estimate of how much sand is actually transported by a hurricane event,” van Hengstum said. “Oyster and Salt Pond are great recorders of past storms, but which layers indicate hurricanes versus just strong storms? Any information provided by this rapid test would allow us to better interpret sand layers in the long-term record. Irene showed us the signal of sand transported by a tropical storm, so anything greater than this signal in the prehistoric sediment record we can now interpret more confidently as a hurricane event.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

As Hurricane Irene approached Cape Cod in August 2011, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution wanted to record how sand and sediment is transported during storms. They made devices using ladies’ nylon stockings. Leah Fine (left), an undergraduate Summer Student Fellow, and WHOI postdoctoral investigator Andrea Hawkes install their makeshift sand-catchers on signs and telephones along the barrier beach on Surf Drive in Woods Hole. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

As Hurricane Irene approached Cape Cod in August 2011, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution wanted to record how sand and sediment is transported during storms. They made devices using ladies’ nylon stockings. Leah Fine (left), an undergraduate Summer Student Fellow, and WHOI postdoctoral investigator Andrea Hawkes install their makeshift sand-catchers on signs and telephones along the barrier beach on Surf Drive in Woods Hole. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- Meanwhile, another WHOI postodoctoral fellow, Pete van Hengstum, deployed sediment traps made out of soda bottles to measure sediment transported by the storm into ponds behind barrier beaches. (Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Hurrying to make their sediment traps in the days before Hurricane Irene approached, “we put a lot of soda down the drain,” van Hengstum joked. (Courtesy of Peter van Hengstum, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Sand and sediment from the beach, mobilized by storm surges and winds, piled onto Surf Drive during the storm, which was downgraded from a hurricane to a tropical storm by the time it reached Cape Cod. (Courtesy of Andrea Hawkes, Woods Hole Oceanographic Instituion)

- The scientists installed 30 sand-catchers along the beach and 30 more sediment traps in shoreline ponds. The humble devices worked well, collecting the data scientist that quantified how much sand is transported by a tropical storm. (Michael Toomey and Richard Sullivan, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- An introduction to marsh bothering

- Wilmington’s shark tooth divers can thank the last ice age for their treasure trove

- Novel tool sheds light on coral reef erosion

- With worsening storms, can the Outer Banks protect its shoreline?

- Dune buggies and diving:

- Adapt or retreat:

- The ocean science-art connection

- Marshes, Mosquitoes, and Sea Level Rise

- More Floods & Higher Sea Levels

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Coastal Systems Group Lab at WHOI

- Scientists Unearth Long Record of Past Hurricanes from Oceanus magazine

- Hurricane Hunter Graduate student uncovers long-buried record of past storms

- Jeff Donnelly

- Andrea Hawkes

- Lakes and Climates Have Their Ups and Downs An article by Jeff Donnelly from Oceanus magazine