An introduction to marsh bothering

A sea-level modeler plunges into fieldwork

WORDS BY HANNAH PIECUCH | NOVEMBER 28, 2022

PHOTOGRAPHY BY HANNAH AND CHRISTOPHER PIECUCH

For WHOI Associate Scientist Christopher Piecuch, studying sea level usually involves long math derivations at a white board and coding at a computer. But the data he uses for those models are based on samples from physical places in the world, such as marshes along eastern North America. In June 2022, Piecuch (below, right) travelled to Prince Edward Island, Canada, with colleagues who collect salt-marsh sediment cores to reconstruct past sea level. It was an entry into field science: where work is planned according to the tides, mud is ever-present, marsh gnats can make a hard day harder, and Piecuch found coring itself a surprisingly satisfying form of physical exertion.

Marsh bothering is a lighthearted name for systematic and careful work. “To get a core that will show past sea level, you need a place with a background level of sea-level rise, so the marsh adds new layers of sediment through the years,” says Andrew Kemp, an associate professor from Tufts University, who led the fieldwork (above, left).

Kemp has been gathering cores and reconstructing past sea level along the North American Atlantic coast for nearly two decades and Piecuch uses this data to model rates of past sea-level change. They needed a sampling location between Maine and Newfoundland to expand coverage within the data series. Prince Edward Island experiences rising seas, has an abundance of marshes, and was accessible for the international science team.

Mapping Underground Peat

To locate the best spots for coring, the team spent more than a week surveying three marshes. They began by tracking the tides at each marsh. Then they spent days on surface surveys, examining the dirt beneath their boots, and taking exploratory cores to determine where they could find the thickest peat. The goal was to take home cores from deep and undisturbed areas of each marsh for detailed laboratory analysis.

Fewer cores, more data

Scientists have used salt marsh cores for decades, but in the past, they were generally used to study geological processes on time scales across thousands of years—such as the rate at which land was rising or falling after the glaciers melted.

The approach Kemp favors means taking fewer cores and analyzing them in more detail. The result is data that shows sea-level change decade-by-decade across millennia.

“Salt marsh cores provide a seamless and continuous record that captures the present and also extends thousands of years into the past,” says Piecuch. “Knowing how sea level has changed lets us know how the solid earth, the ocean, and climate have changed and that gives us a picture of how what we’re experiencing now is unique.

A journey through time

In order to turn these salt marsh cores into a figure that shows age and sea level, the sediment is first sliced up by centimeter. Then, it is analyzed for age using an isotope detector for the last 150 years, and radiocarbon dating for layers older than that.

Once the age of the sediment is known at each depth, the researchers need to determine where sea level was when it was at the top of the marsh. To do that, portions of the same sections are spread over microscope plates so the foraminifera—single-celled organisms often referred to as forams—can be counted.

In salt marshes, forams make a shell by gluing pieces of sediment to themselves. Different species favor different depths in a marsh, and can show whether a sample of sediment is from a high portion of a marsh or directly at sea level.

A boot in both worlds

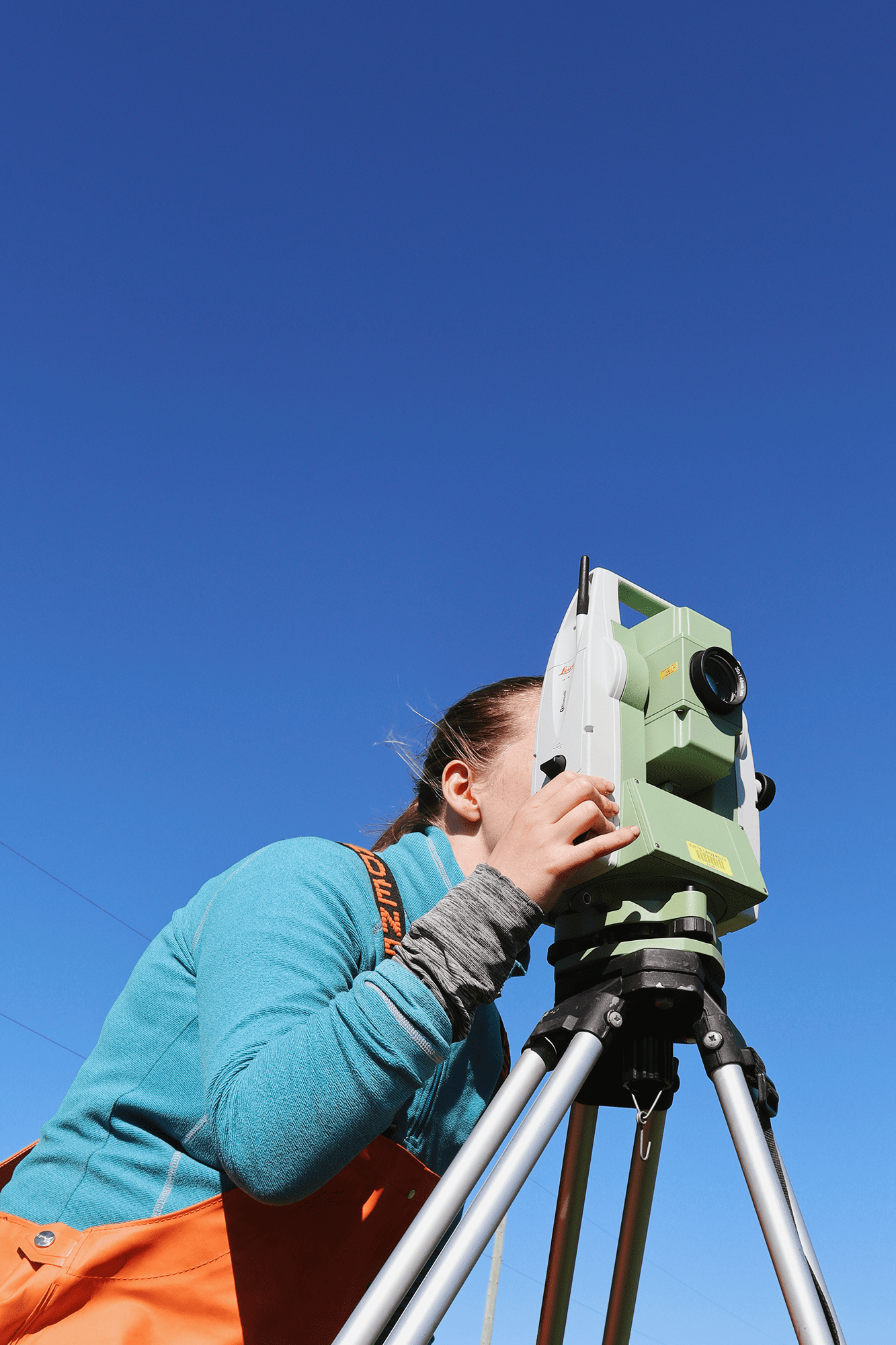

While field science and modeling are often carried out by separate scientists, Kelly McKeon (above), a doctoral student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program, aims to do both.

The science party on Prince Edward Island was composed of people who work across the whole range of disciplines in reconstructing past sea level.

“I gained a lot of new connections,” McKeon says, “I have field experience, but not in sea-level reconstructions. The reason I am working with Chris is to learn how to do sea-level modeling. Before this trip he was the only person I knew in that space.”

McKeon sees modeling as a key to gathering better salt marsh samples. “Numerical models can help predict what we should see in field data and validate the observations we make there.”

A new view of Salt Marsh Data

Having modelers along benefited everyone, Kemp adds. “Usually, modelers and field scientists have only brief opportunities to interact at conferences,” Kemp says. “My goal was to offer the space and time for longer discussions in a casual atmosphere.”

The time and space paid off, especially during evening lectures where each member of the science party could present something they were working on and then spend an unpressured hour discussing it.

“Zoë Roseby—a scientist from Trinity College Dublin—was looking at how much sea level rose in Dublin from 1700-2000,” Kemp says. “Piecuch explained how that question should be answered. Then Maeve Upton—a modeler from National University of Ireland Maynooth—and I spent an evening locating the numbers we needed, and I actually used that approach in a paper where we had the same question for a different time and location.”

For Roseby—who analyzes salt marsh samples to reconstruct sea level on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean—having modelers give feedback on her research was especially helpful. “It really helped me understand what my results mean when I use these modeling methods. I came away feeling really motivated and knowing how I can write about my data.”

Working in the field has already enriched Piecuch’s work. “It allowed me to see the reality that the data describes,” he says. “I am now able to more accurately represent that process in the models I build, which means I’ll produce more accurate estimates of sea-level change.”

Fieldwork funded by the National Science Foundation: Christopher Piecuch, WHOI, through the Paleo Perspectives on Climate Change program; and Andrew Kemp, Tufts, through the Faculty Early Career Development award. The science party included: Emmanuel Bustamante, Tufts; Andrea Hawkes, University of North Carolina Wilmington; Maeve Upton, National University of Ireland Maynooth; and Robin Edwards, Zoë Roseby, and Fermin Alvarez Agoues, Trinity College Dublin. Photos taken at Jacques River Marsh, Tryon Marsh, and Wolfe Inlet on Prince Edward Island, Canada.