Junk Food

Do microplastics in the ocean pose health risks?

An estimated eight million tons of plastics enter our oceans each year, yet only one percent can be seen floating at the surface. This is the third in a three-part series of stories about how researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are trying to understand the fate of “hidden” microplastics and their impacts on marine life and human health.

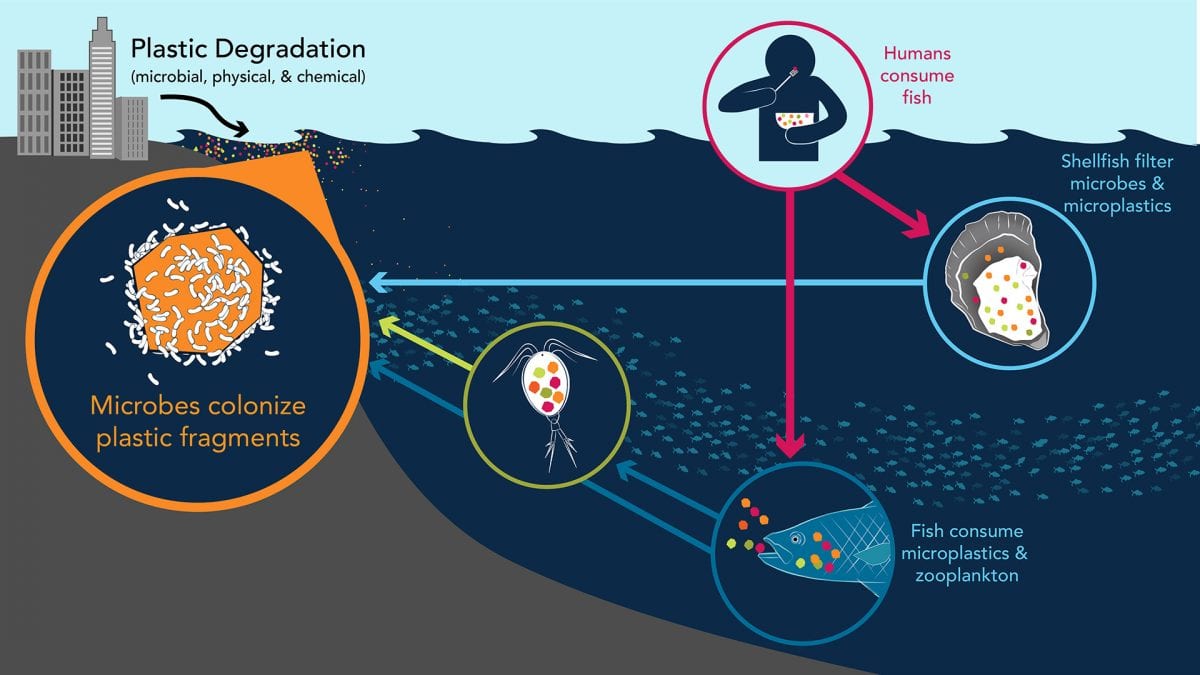

Microplastics may appear tiny—most are smaller than the fingernail on your pinky—especially when compared to larger plastics floating around the ocean such as bottles and bags. But as small as they are, a single particle is big enough to provide housing for thousands of microorganisms that cling to them. Together, they form communities of what some scientists refer to as the “Plastisphere” of the ocean.

Plastic bits may seem like one of the ocean’s stranger habitats, but they provide available real estate for microbes. As they drift through the ocean for a while, they act as tiny rafts on which bacteria and algae can hitch a ride and settle down and form colonies.

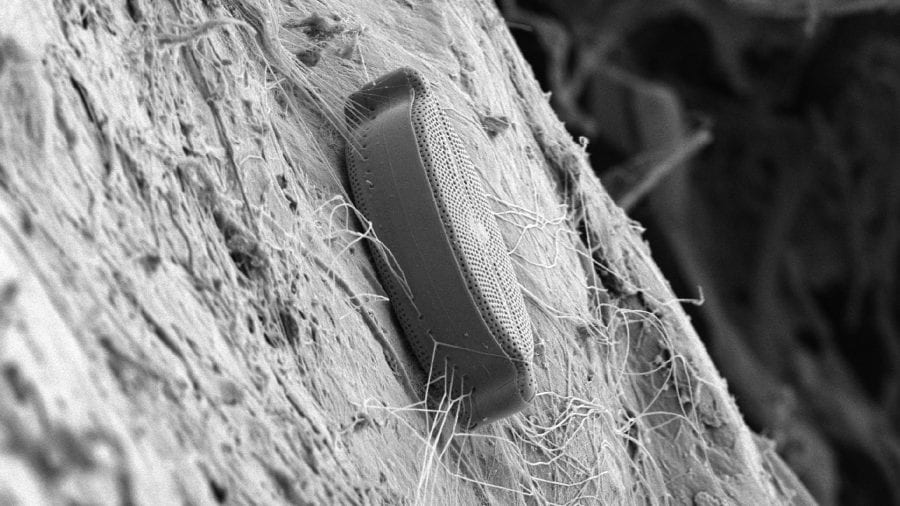

Plastic particles might also provide a microbial food court. They may not sound appetizing to us, but it’s possible that microbes may eat them. In a 2013 study looking at the microbial colonization of plastic marine debris, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the Marine Biological Laboratory placed microplastics collected from the ocean under high-powered microscopes. They found not only diverse communities of microbes living on the them, but also chunks of material or “pits” missing from the fragments. Scientists, however, stress that more evidence is needed to confirm whether microbes consume plastics.

Over time, the microbes form a biofilm coating on the microplastic fragments. Scientists believe this entices fish, which may not know the difference, to gulp down food-covered microplastics and push them further up the food chain.

Scallops, for example, ingest plastic particles as they filter seawater. In recent years, deep-sea scallops collected during surveys off Cape Cod, Mass., showed traces of microplastics in their guts, according to WHOI scientist Scott Gallager.

“Once we dissected them and scanned their gut contents,” explained Gallager, “we saw that these animals had ingested microplastics. In fact, we discovered six different types of polymers in these scallops.”

While the associated health impacts to sea scallops aren’t yet clear, there is reason to think that microplastics and marine life aren’t a good mix in general. For example, a 2018 study investigated the link between plastic waste and disease risk in more than 120,000 reef-building corals throughout the Asia-Pacific region and found that the likelihood of diseases increases from 4 percent to a whopping 89 percent when corals are in contact with plastic.

If it turns out that microplastics are dangerous for shellfish and other types of marine animals, what does that mean for seafood lovers? Plastics may contain phthalates, bisphenol A, and other toxic chemicals used in manufacturing processes. These additives can change the properties of plastic items in different ways. They can make your soda bottle more rigid and your pen more flexible. Microplastics also suck up harmful chemicals from the environment, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which have been directly linked to human health problems.

According to Amy Apprill, a microbial ecologist at WHOI, there’s also speculation that some of the microbes residing on microplastics are pathogens. “That can spell trouble for marine animals and possibly humans that consume plastics,” she said.

But Mark Hahn, a toxicologist at WHOI, says there’s a lot of controversy around the question of how dangerous microplastics are. Some feel the risk is trivial compared to the risks from exposure to other environmental stressors, whereas others see exposure to microplastics as an urgent problem.

To settle the score, Hahn feels it will be important to first determine which types of microplastics we’re most concerned about and then determine how much of them is being ingested by marine animals, including seafood.

“By combining these two pieces of information, we can assess the risks for marine animals and humans” he said.

For now, however, Hahn says there are a lot of unknowns.

“Are microplastics taken up and internalized in humans, or do they pass right through the gut?” Hahn asked. “And what is the relative contribution of seafood versus other sources of microplastics we’re exposed to? We inhale microplastic particles all the time. There are still many more questions than answers.”

For more information about WHOI’s Marine Microplastics Initiative, visit microplastics.whoi.edu.

Other Oceanus stories in this series:

Part 1: Sweat the Small Stuff

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

The video shows that scallops ingest plastic particles as they filter seawater. In recent years, deep-sea scallops collected during surveys off Cape Cod, Mass., showed traces of microplastics in their guts, according to WHOI scientist Scott Gallager. (Scott Gallager, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The video shows that scallops ingest plastic particles as they filter seawater. In recent years, deep-sea scallops collected during surveys off Cape Cod, Mass., showed traces of microplastics in their guts, according to WHOI scientist Scott Gallager. (Scott Gallager, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- An image from a high-powered microscope reveals a microbe that has colonized a microplastic fragment collected in the North Atlantic Ocean. Such microbes enticed fish to ingest microplastrics. (Erik and and Linda Amaral-Zettler, NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research)

- Fish—including shellfish and finfish like the one shown here—ingest microplastic fragments in the ocean. However, the health risks of microplastics to fish and humans that eat them are unclear. (David Lawrence, Sea Education Association)

Related Articles

- How is human health impacted by marine plastics?

- WHOI establishes new fund to accelerate microplastics innovation

- Microplastics in the Ocean – Separating Fact from Fiction

- Particles on the Move

- Do Microplastics in the Ocean Affect Scallops?

- Tracking a Snow Globe of Microplastics

- Sweat the Small Stuff

- From Macroplastic to Microplastic

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Sweat the Small Stuff Part 1 in Oceanus series on microplastics

- Tracking a Snow Globe of Microplastics Part 2 in Oceanus series on microplastics

- Marine Microplastics Initiative

- Behold the Plastisphere from Oceanus magazine