Sweat the Small Stuff

Tiny plastics prompt big investigation

An estimated eight million tons of plastics enter our oceans each year, yet only one percent can be seen floating at the surface. This is the first in a three-part article series about how researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are trying to understand the fate of “hidden” microplastics and their impacts on marine life and human health.

When we think of plastic in the ocean, we often think of easily seen things such as water bottles and plastic bags. In reality, the vast majority of plastics in the ocean are smaller than a millimeter and can’t be seen with an unaided eye; some particles resemble bird seed, others look like dust.

These small fragments are known as microplastics. Some are “micro” by design: Microbeads, for example, are tiny plastic spheres manufacturers add to body washes, toothpastes and other products to give them extra scrubbing power. Lentil-sized pellets known as nurdles are ubiquitous fodder used in the manufacture of many common plastic products, are also intentionally small.

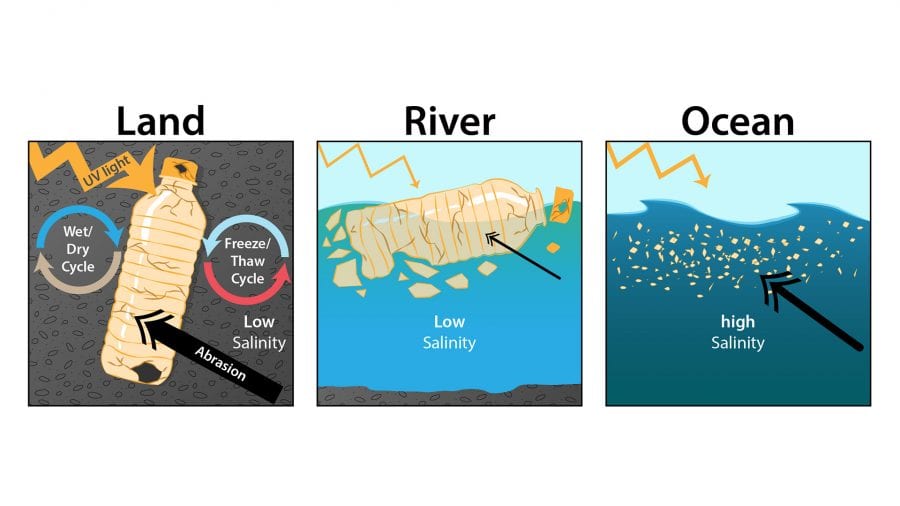

Other microplastics become “micro” over time when larger pieces of plastic debris, such as water bottles, straws, cups, and car fenders, are exposed to forces of nature that cause them to degrade. Sunlight, for example, oxidizes plastic and causes it to weather and degrade. Freeze-thaw cycles can weaken the structure of plastics over time. And ocean waves could also be taking a toll, making plastics more brittle by constantly washing over them and grinding them into sand.

Scientists have a decent sense for the types of physical and chemical weathering processes that can cause plastics to break down. However, little is known about how quickly degradation happens, and whether most of it is happening on land, in rivers, or in the ocean. It’s unclear, for example, what happens to a plastic water bottle between the time someone takes his or her last swig and when the empty bottle ends up in the ocean, said WHOI senior scientist Chris Reddy.

“There’s a perception that most of the fragmentation of plastics is happening in the ocean, but it could be that a lot of the activity is actually happening on land,” he said. “For example, if you take a red ‘Solo’ cup and leave it on the ground outside for a week, you can see that the red color starts to fade to pink and that the cup is more brittle. So, pre-aging on land could be playing a major, currently unaccounted for role in the fate of plastics in the ocean.”

Another big unknown is the impact marine microbes have on the breakdown of plastics in the ocean. Studies have demonstrated that microbes cling to even tiny plastic fragments, and nibble at them as well. But whether they are causing any significant breakdown of the material is something that scientists at WHOI are just starting to investigate.

The uncertainty surrounding where and how quickly plastics break down has become a critical knowledge gap not only for scientists, but also for chemical companies and plastic manufacturers that want to design plastics that decompose faster into materials that are non-harmful and have minimal effects on the environment.

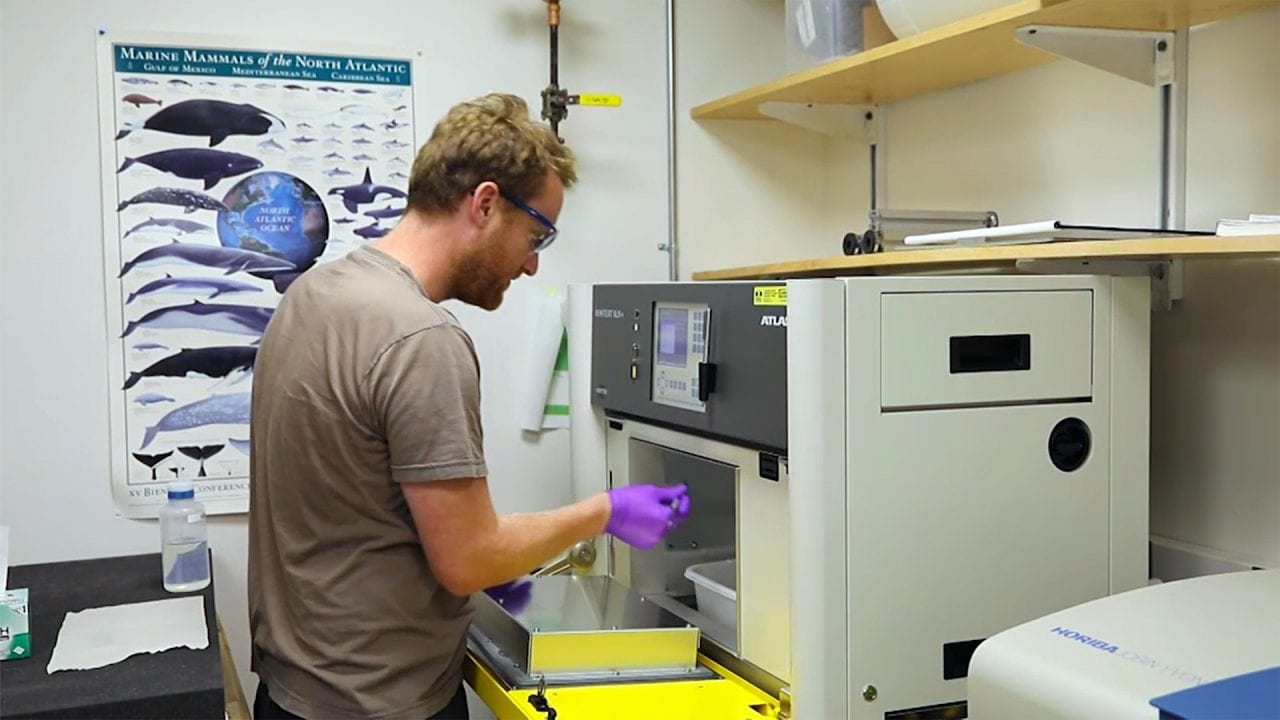

One way to gauge the speed of degradation is by placing plastics—including “raw” plastics containing no additives, as well as consumer products such as Styrofoam cups—in specialized weathering chambers. Scientists can conduct experiments in these chambers that test how factors such as sunlight, temperature, and humidity contribute to physical breakdown processes.

“These chambers provide a realistic picture of what happens on land and in the ocean,” Reddy said.

Collin Ward, a marine chemist at WHOI, says one of the main advantages of the weathering chamber is speed: It can accelerate the weathering process to answer environmentally relevant questions faster. When testing the effects of sunlight, for example, the chamber’s light source can be cranked up to flood plastics with ultraviolet light that is ten times more intense than natural sunlight.

“Some of the longest experiments I’ve ever run have been on plastics, and the reaction times are very slow since plastics are designed to not break down easily,” he said. “With these chambers, we can easily get the equivalent of a month’s worth of sunlight in one week, so it really accelerates the weathering.”

Weathering chambers will help, but Ward says that gaining a true sense for how plastics breakdown will be far more complex than simply blasting them with sunlight in a box. This is due to the fact that there are so many different types of plastics, and each type may break down at different rates in the environment due to the base polymers used and the types of additives and pigments applied to the materials during the manufacturing process.

“Cellulose acetate is completely different from polystyrene and polyethylene,” he said, “so these products will weather at different rates and by different processes. And then you have plastics that come in various colors, each with their own pigments and additives that can initiate the fragmentation process at different rates. When you consider all the variables that can impact the breakdown process, it becomes an incredibly complex science question.”

For more information about WHOI’s Marine Microplastics Initiative, visit microplastics.whoi.edu.

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI marine chemist Collin Ward places a piece of plastic into a weathering chamber which can test how environmental factors such as sunlight and temperature influence the breakdown of the material. (Photo by Matt Barton, WHOI Creative)

- Currently, little is known about when and where larger plastics break down in the environment to form microplastics. A common perception is that most of the fragmentation occurs in the ocean, but pre-aging of plastics on land could play an important role. In addition to understanding the timing of plastic degradation in the environment, scientists are studying the chemical and weathering processes responsible for the breakdown of larger plastics, such as sunlight, temperature, salinity, humidity, freeze/thaw cycles, and abrasion. (Illustration by Natalie Renier, WHOI Creative)

Related Articles

- How is human health impacted by marine plastics?

- WHOI establishes new fund to accelerate microplastics innovation

- Microplastics in the Ocean – Separating Fact from Fiction

- Particles on the Move

- Do Microplastics in the Ocean Affect Scallops?

- Junk Food

- Tracking a Snow Globe of Microplastics

- From Macroplastic to Microplastic

Featured Researchers

See Also

- From Macroplastic to Microplastic An estimated eight million tons of plastics enter our oceans each year, yet only one percent can be seen floating at the surface. Researchers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are trying to understand the fate of “hidden” microplastics and their impacts on marine life and human health.