Microplastics in the Ocean – Separating Fact from Fiction

WHOI scientists weigh in on the state of marine microplastics science.

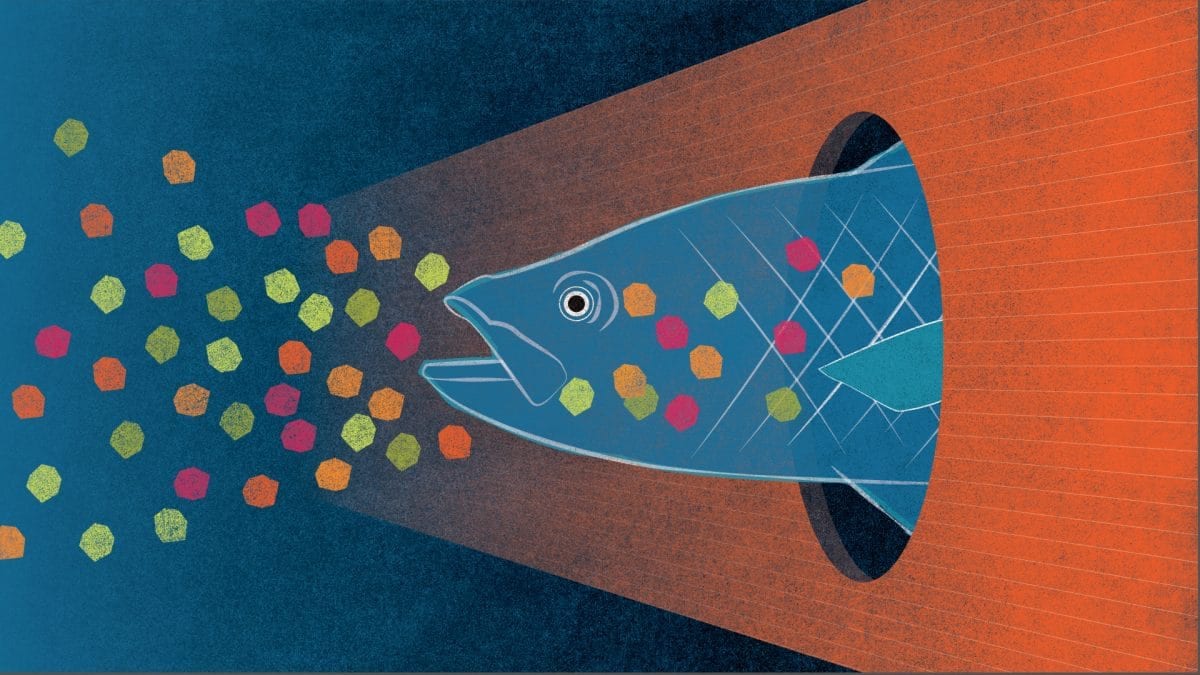

Last year, Gizmodo ran a story reporting on evidence that microplastics – plastic fragments less than five millimeters size (roughly a quarter inch) – are moving through the marine food web to top predators. The study, published by researchers at the University of Exeter, showed that when mackerel consumed microplastics and were later fed to seals, the plastic bits could be detected in the seals’ fecal samples.

While the story reinforced a logical concept—that microplastics consumed by smaller marine animals may eventually end up in larger ones—it touched on the question of how harmful microplastics are to marine life and humans, if at all. One scientist, who was not involved in the study, commented, “There’s lots of work still needed before we understand microplastics’ potential harm to animals, how long those plastic bits stay in digestive tracts, and how they accumulate. There isn’t much convincing evidence of harm to humans yet.”

More recently, scientists from the University of Connecticut expressed a similar sentiment in a commentary published in the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association (ECSGA) newsletter. In the story, the authors questioned whether microplastics are having negative impacts on marine animals, and suggest that many of the published microplastics studies to date may not be based on sound science.

At Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), the message strikes a chord. WHOI has recently launched a research initiative to investigate the fate of microplastics in the ocean and their associated health and environmental impacts. According to the project’s website, “the field of marine plastics is at a crossroads, and is in danger of taking the path towards mediocrity.”

Marine microplastics are nothing new to the WHOI. Scientists there were finding the confetti-like particles in the ocean back as early as the 1970s, when they published studies on the discovery of microplastics in locations as nearby as the coastal waters of southern New England and as far away as the Sargasso Sea. But today, the WHOI science team, which includes scientists spanning a range of disciplines including biology, chemistry, and physical oceanography, feels that more and better science is urgently needed to fully understand the issue of marine microplastics and what harm, if any, they are causing.

“The number of papers being published on microplastics has grown exponentially in the past few years, but the quality of the studies is highly variable,” said Mark Hahn, a toxicologist at WHOI who is part of the research initiative. “Some of these studies don’t use the most rigorous experimental designs and conditions. It’s like any new field where there’s a rush of people to get into it and a rush to get papers out.”

Hahn and his colleagues feel that one of the things getting in the way is the general lack of agreed-upon standards used in microplastics science—standardized materials, methods, technologies, and even terminology.

“There isn’t even agreement on how scientists define microplastics and nanoplastics,” Hahn said.

WHOI chemist Chris Reddy agrees that the lack of standards is an issue, and also feels that people generally have a very limited understanding of the complexities of plastic. He also recalls numerous examples in chemical oceanography where it took decades before accurate measurements of elements, like iron and lead, were comparable across the scientific community. But he cautioned that studying plastics is harder.

“Unfortunately, plastics are a considerably more challenging field of study,” he said. “There are six different types of consumer-based plastics, all made from different polymers with different sizes, thicknesses, colors, and additives. There’s been a misunderstanding out there that we know a lot about plastics, but in reality, we don’t. It’s a really complex problem.”

Reddy expects it may take a decade or two before the field of plastics matures to a point where robust discussions among scientists and engineers can take place. He says he wants to press the “reset button” on microplastics science, slow things down, and work with the science team to bring the science to a level where well-informed decisions and policy can be made.

“There’s too much hype, and too many microplastics papers coming out saying the sky is falling,” he said. “But we’re very much still in the wild west, and the data just isn’t there to support these claims.”

Both Hahn and Reddy do feel that in time, the quality of microplastics research will improve, provided that standards are developed and studies become more rigorous. Hahn says he already sees some positive signs in some of the latest published papers, and feels that the field as a whole is starting to recognize some of the past pitfalls in the science.

Reddy agrees, but feels that scientists need to also do a better job communicating what is good, acceptable plastic science to the scientific journals.

“Mediocre papers have been getting A+ plus scores that are C papers at best,” he said. “Good scientists are great skeptics, so we need to do what we can to help separate fact from fiction and encourage more rigor as the field continues to grow.”

He adds, “Good science takes time and scrutiny, and we will reach a point where plastics research will reach a higher-bar. I’m confident of it.”

From the Series

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Sweat the Small Stuff Oceanus Magazine

- Tracking a Snow Globe of Microplastics Oceanus Magazine

- Junk Food: Microplastics in the Food Chain Oceanus Magazine

- Do Microplastics Affect Scallops? Oceanus Magazine

- Particles on the Move Oceanus Magazine