Jellyfish larger than blue whales?

WHOI scientists weigh in on recent jelly sightings in Massachusetts

By Kenneth Kostel | June 26, 2020

Recent accounts in the media have described the appearance of lion’s mane jellyfish in waters and beaches in the Northeast as a surprising, sometimes troubling, event, with record sizes and numbers reported from Maine to the Massachusetts south coast. But is this event noteworthy? Or, as some have implied, is it a sign of failing ocean health? Three WHOI marine biologists weighed in to put events into perspective.

How big are the jellies that have been washing ashore?

Several news stories have described one or more jellies that washed ashore as the largest on record or that the lion’s mane jelly is the largest animal in the ocean. Both of those claims are not entirely true or difficult to corroborate. For one, it’s challenging to accurately measure a jelly out of the water, as gravity will compress and spread the bell, which makes up most of a its mass. A bell measuring four feet across on the beach would appear much smaller if the same animal were floating in the water.

In addition, WHOI Senior Science Advisor and marine biologist Larry Madin noted that references to the lion’s mane jelly as larger than the blue whale are based primarily on an uncorroborated 100-year-old record. Even if it were true, he pointed out, that assessment would include the animal’s tentacles. “Yes, the tentacles are long, but they’re tentacles,” he says. “They’re not the body of the animal. There’s no way they could compare to a blue whale.”

Is this event unusual or troubling?

According to WHOI Research Specialist Annette Govindarajan, it’s often difficult to say whether events like these are unusual because records of jellyfish are often anecdotal and inconsistent. Normally, she said, researchers would collect data on the timing of blooms, as well as size abundance of jellies over long periods of time in order to assess whether the outbreak is being driven by specific environmental conditions.

“This is why we study these animals over long periods, so that when these events happen, we can put it in perspective and understand if it’s unusual," says Govindarajan.

Because jellies are not especially strong swimmers, their distribution is most often controlled by physical factors, such as currents and wind. In addition, lion’s mane jellies have an early life stage known as polyps. When jellyfish reproduce, they release gametes that fertilize and form larvae. Once attached to a hard surface or the seafloor, the larvae transform into small polyps near estuaries and river mouths during the late summer and early fall. Through asexual reproduction, one polyp can produce many jellyfish, culminating in a bloom the following spring. Conditions throughout that cycle, including water temperature and food supply, can determine the success of one species or another, which means there are many factors at work in any given year. Scientists say it is important to have a monitoring effort to track and predict blooms from year to year like they do for harmful algal blooms.

One trend worth watching is rising water temperatures. As warmer water moves north and more frequent intrusions of Gulf Stream water occur in the region, more southern species have begun showing up in local waters. In addition, warmer temperatures could potentially promote the polyp stage. One example is moon jellies, which have expanded their range north as waters have warmed and are a common sight around Cape Cod. Still, Govindarajan is careful about not attaching a cause to the current bloom without knowing more. “When jellyfish blooms happen, many people blame human activity. But you can’t answer that question without baseline data.”

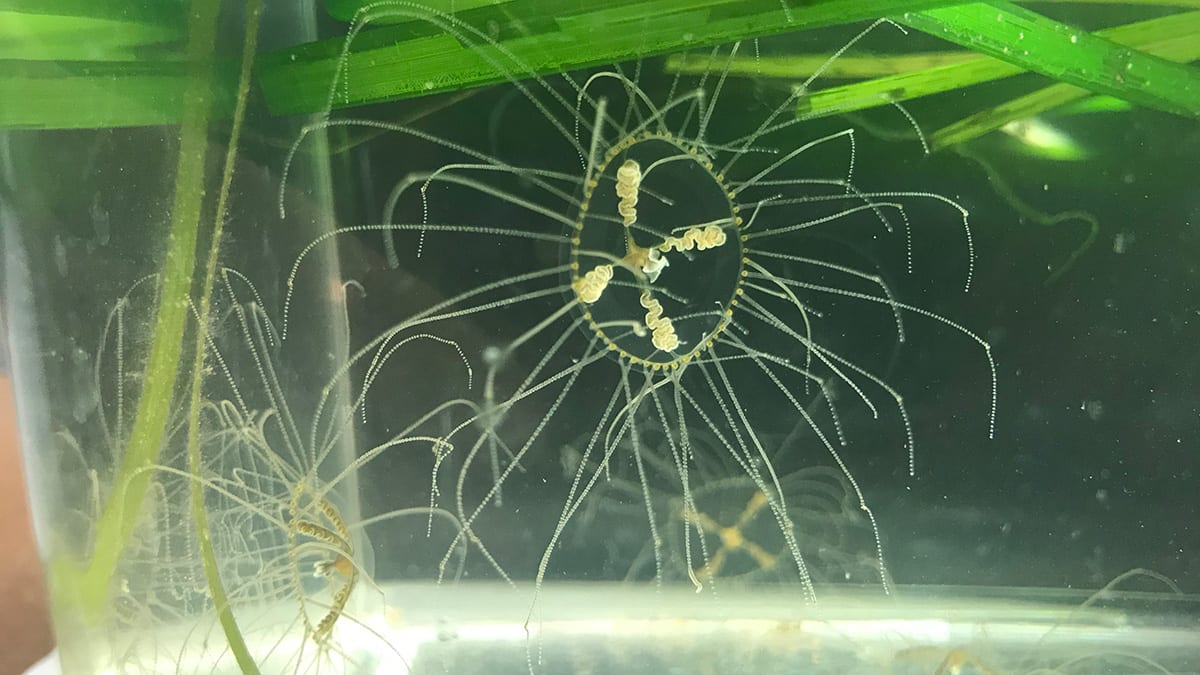

Another question is how an increased number of jellies, particularly species that are new to the region, might affect an ecosystem unaccustomed to their presence. Mary Carman, a WHOI guest investigator, who, along with Govindarajan, studies the ecology of jellies, in particular the cryptogenic (of unknown origin) and highly toxic clinging jelly (Gonionemus sp.) in eelgrass meadows of Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, also has a long history of studying the predator-prey relationships of jellies.

The key questions in Carman's mind are, first, whether the current bloom is an indication of a shift in range or a one-off event and, second, whether the introduction and proliferation of a new species will have an effect on populations of things they eat—in the case of lion’s mane jellies, juvenile fish, shrimp, and tiny crustaceans known as copepods.

“When you study invasive species, you have to be careful to see it in more than one location over multiple years to make sure they’re surviving in their new range,” Carman says.

Are these jellies dangerous?

Lion’s mane jellies do sting, says Carman. “It’s definitely noticeable—not as bad as clinging jellies, but they do sting and people who have an allergic reaction to them should be careful.”

Unlike clinging jellies, which prefer marshy areas, Carman notes that lion’s mane jellies prefer to float along the surface of rocky shorelines and sandy beaches—places that people frequent. As a result, they’re more likely to come into contact with swimmers or people wading in the water. In addition, stinging cells in the tentacles remain active if a jelly has washed ashore or has been injured by a boat, so people walking on the beach or swimmers who do not see jellies in the water could still be stung.

What can people do?

The most important thing people can do is report sightings of jellies on shore or in the water by sending photographs to jellyfish@whoi.edu. It's helpful if the photograph includes an object of known size in the frame to help Govindarajan and others assess scale. People should stay far enough away that they are not in danger of being stung, especially in the water, where the tentacles might be difficult to see. This is especially true for clinging jellies, which can cause a painful sting, sometimes requiring medical treatment. In addition, says Madin, it’s important to remember that the ocean is their home, not ours. “Some years there are more than others, sometimes wind and currents bring them to shore,” he says. “They’re out there in the ocean.”