Overhaul to take Alvin to greater extremes

Work on iconic sub will put 98% of the ocean floor within reach

By Hannah Piecuch | July 8, 2020

Alvin is transferred from R/V Atlantis to the high bay at WHOI’s water-front facility in early March. The overhaul is a continuation of more than 50 years of improvements to the vehicle as it evolves to meet the needs of the science community. (Video by Craig LaPlante and Matthew Barton © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The Human Occupied Vehicle (HOV) Alvin returned to Woods Hole, Mass. this spring for the final phase of an overhaul that will allow the submarine to dive to 6,500 meters.

This increased depth range will give ocean scientists the ability to explore 98% of the ocean floor and study the abyssal region—one of the least-understood areas of the deep sea and home to high-temperature hydrothermal vents, submarine volcanoes, subduction trenches, mineral resources, and more. The sub was previously rated to 4,500 meters, but the upgrade will make Alvin the only publicly-funded, human-occupied vehicle available to the U.S. scientific community for exploring the abyssal region in person.

“There is an arc we can follow with Alvin as an iconic tool for exploring the ocean,” says Andrew Bowen, director of the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF). “With a submarine that can dive to 6,500 meters we will have an integrated system that allows the ocean to be explored to the fullest extent. As the centerpiece of the Facility, Alvin will soon be able to deliver humans into this harsh environment.”

Located at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, NDSF is funded by the National Science Foundation, U.S. Navy, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and operates Alvin, remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason, and autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry for the ocean science community.

Alvin Upgrade Timeline

May–June 2020

Disassembly

June–July 2021

Maintenance and modifications

June–February 2021

Ballast sphere machining, welding, and testing

March–July 2021

Reassembly

July–August 2021

Testing

August–September 2021

Sea Trials

Check back for more stories and video as the overhaul continues through 2021*

Danik Forsman, Anthony Tarantino, Nick O'Sadcia, and Rod Catanach remove the syntactic foam from atop the sphere. Syntactic foam is made up of small balloons of glass, mixed with epoxy into a matrix and formed into blocks, which are then shaped into a custom shape for Alvin. A deeper-diving Alvin requires new syntactic foam that is tested to withstand the additional pressure at 6,500 meters. (Photo by Drew Bewley © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

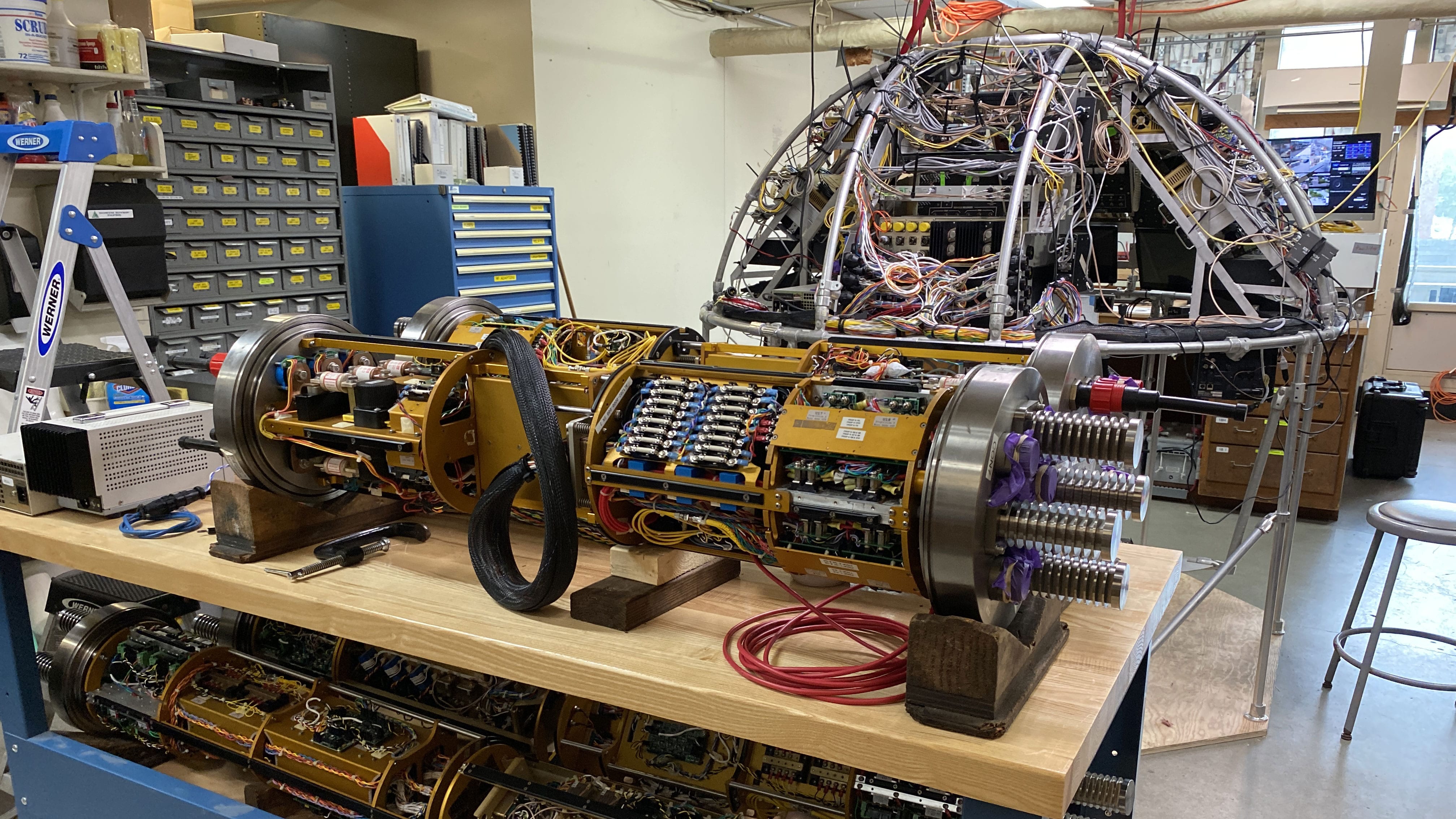

Since arriving in port in March, the sub is now reduced to its component parts. The syntactic foam that gives the vehicle buoyancy and much of its exterior shape is stripped away. The personnel sphere is empty of the screens and control panels that make it the command center for the vehicle. And the sphere has been removed from the vehicle itself so every inch can be inspected for integrity.

Although Alvin has been operating since 1964, the vehicle was significantly rebuilt in 2013 during an overhaul that included forging a larger titanium personnel sphere and rebuilding much of the sub from scratch. These improvements were made with the 6,500-meter capacity in mind, but left several critical steps for the final phase, which will be completed over the coming months.

To reach the new maximum depth, Alvin needs new titanium ballast spheres and several of its syntactic foam modules need to be replaced with foam rated to withstand the increased pressure at 6,500-meters. Additional improvements include an upgrade to the hydraulic system, new thrusters and motor controllers, and updates to the vehicle’s command and control system, says Project Manager Anthony Tarantino.

The upgrade will take a year partly due to the unique nature of the submarine, Tarantino says. “There’s no economy of scale. You can’t just buy these components off the shelf. More than 80% of the vehicle is custom made.”

Upgrading Alvin is usually a collaborative process with 20 or more people coming and going from the high bay at WHOI’s waterfront facility. In order to follow COVID-19 guidelines during this final phase, however, the team has been scaled down, is wearing masks, limiting the number of people on site, and distancing whenever possible. In keeping with WHOI’s protocols, each person must complete a daily health self-assessment before coming to work.

The pandemic has impacted the effort in different ways, Tarantino says. “There’s some team building that gets missed. But everyone understands the environment we’re living in right now. We’re making it work.” Regardless of the challenges, the project continues to move ahead on schedule.

While the Alvin Group digs into the upgrade, deep-sea scientists are convening a NSF-funded workshop to establish research priorities for the next phase of exploration in the abyssal region.

“These are unique ecosystems that have had to evolve around extremes—like the high temperatures of hydrothermal vents or the low-energy environments of abyssal plains,” says Adam Soule, Chief Scientist for Deep Submergence at NDSF. “The freedom of an untethered vehicle is going to be really helpful in an environment where we know very little and have to use our observation skills to decide where to go and what samples to collect.”

In addition to fostering collaboration through the workshop, Soule hopes to recruit the next wave of Alvin users. “Sometimes the sub is viewed as inaccessible to early career scientists or those who haven’t used it yet,” he says. “That is not true. If someone has a good idea and they want to use Alvin, they will get to use Alvin. And WHOI, NDSF, and myself will help them do that.”