In 2008, I was living in Alaska, working as a wilderness guide for troubled youths, and came home to Cape Cod for Christmas. I ended up shooting the breeze with a family friend who works here at WHOI, and he told me about the Arctic and all the research we did there. We swapped stories about outdoor survival stuff, and I remember thinking that I could help their program too, because it seemed like they were taking scientists out into the Arctic without, really, a backup plan.

And then, not too long after that, I got a phone call from [some WHOI folks] and they were like, “Can you get on a boat and go to Russia for 65 days? Can you be here in two weeks?” So I worked in Woods Hole for eight days, then left and flew to Russia. It was a 63-day endeavor where our visas expired because the ship got stuck and all sorts of amazing things. At that time, I didn't have a stress in the world. My colleague Kris Newhall was on the phone all day, and I was taking walks and enjoying the scenery. I did a lot of Arctic trips for the first five years, then in 2012, I decided I wanted to be home more.

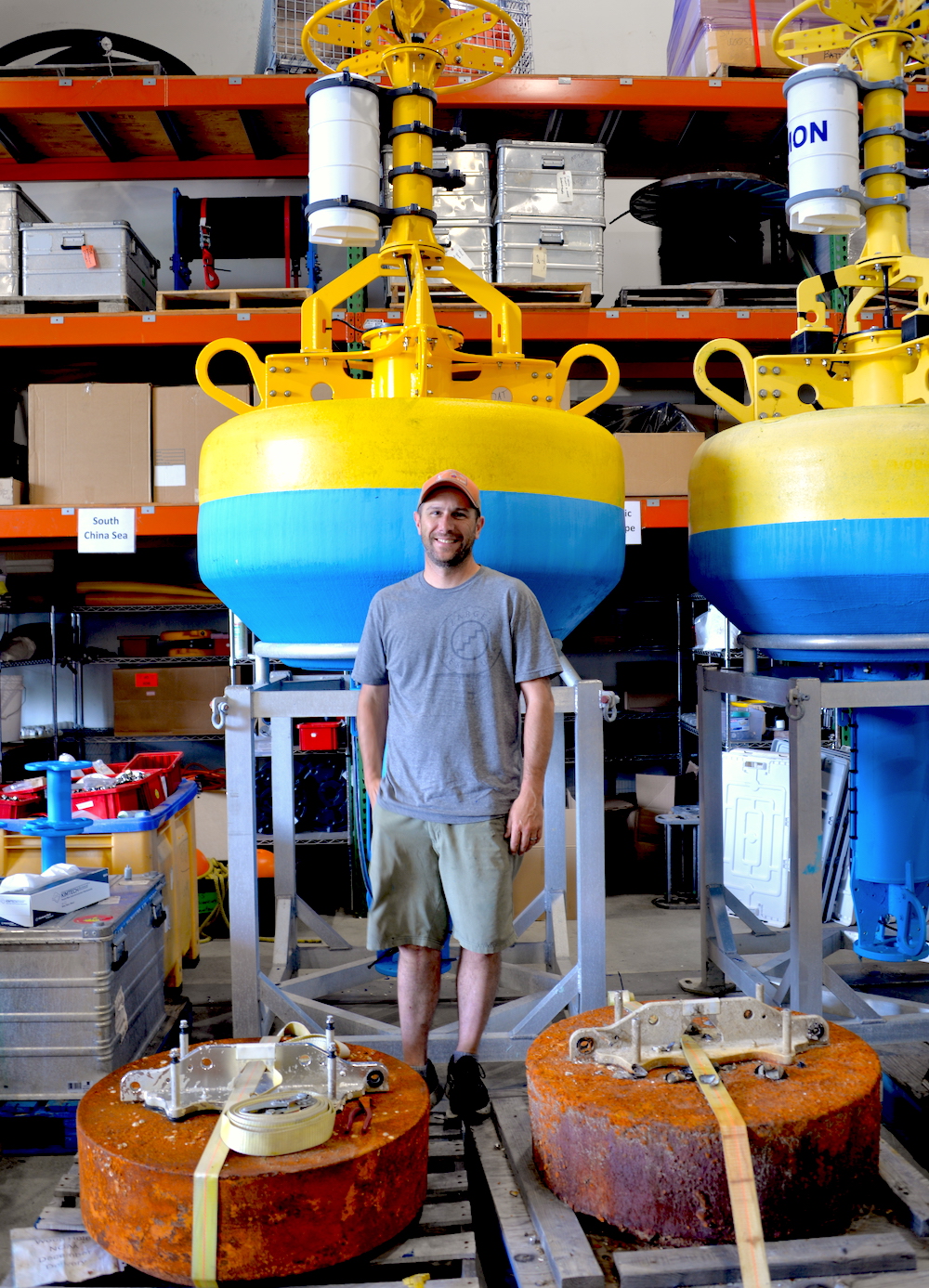

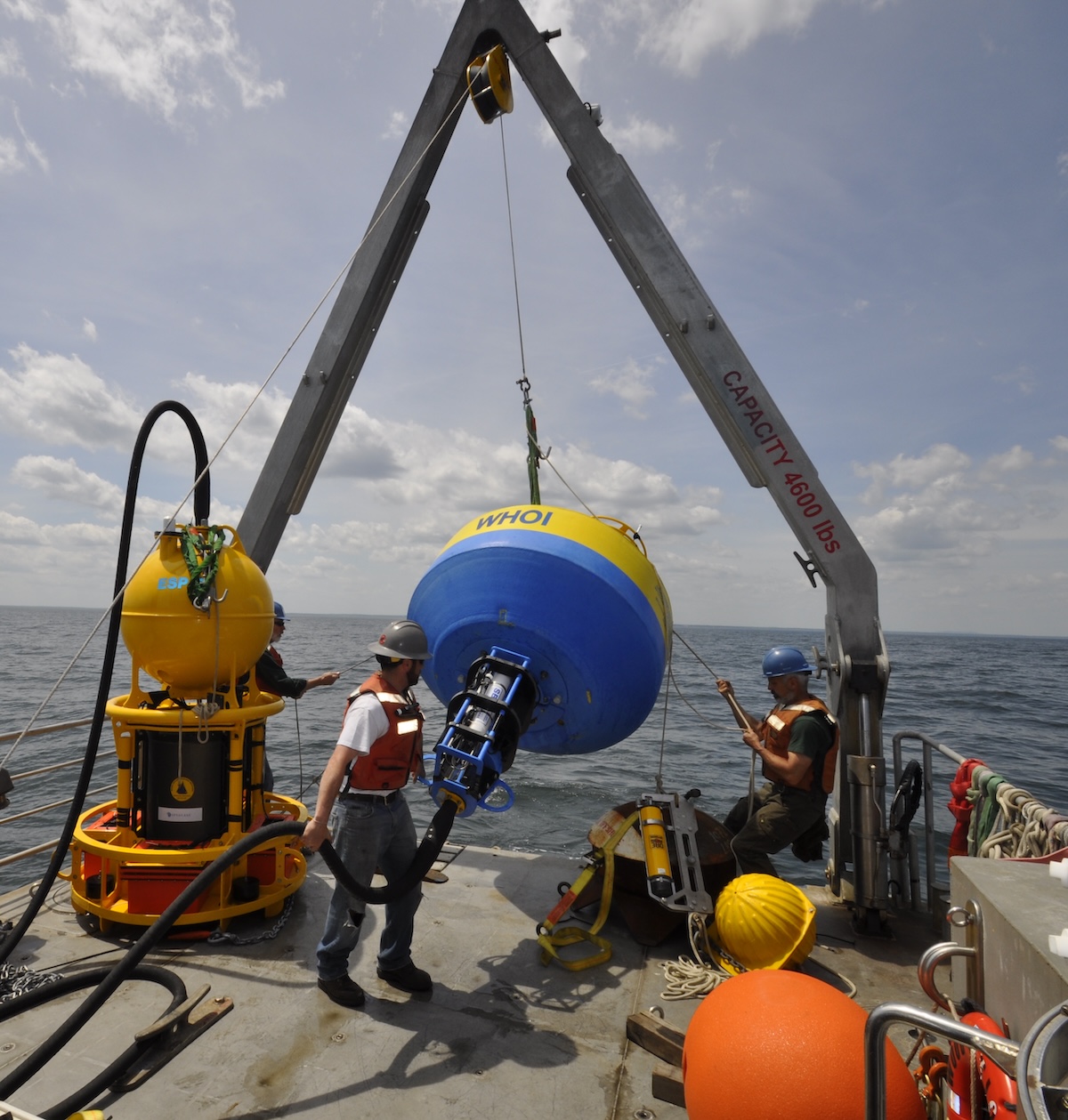

It was good timing because the OOI [the Ocean Observatories Initiative] was starting up. And we build a lot of their equipment. So the home life for our group got very busy, very quick. Then [WHOI biologist] Mark Baumgartner started his Robots 4 Whales project. At first, we lent him the equipment that we had had up in our boneyard. He had this idea to use moorings to listen for whales and send an alert when they’re passing through shipping lanes. We took the idea up to the Gulf of Maine, deployed his mooring, tested his instrument, and, you know, found out that it was gonna work.

Mark's project has continually grown every year since we've started. Now we're up to nine systems: seven on the East Coast, two on the West Coast. And we just got funded for more. So it's a lot busier for me. I'm gone like once a month, anywhere between two to seven days. And so I do a little bit more time at sea, but there’s even more to do at home because of all the refurb and getting the next set of moorings ready and pulling the old equipment out.

This whole line of work is on-the-job training. There is no school for it. You get out on a boat and something happens. Things get weird and you rely on your instincts and on the other people around you to make a decision. And I'd say most of the time, it's probably the right decision. And then you learn from it the next time.

It's very similar to the job I had as a wilderness guide out in Alaska. Whether that's helping a scientist achieve their goal, or it's the guy next to you trying to build something and you can help him with that, or a person just runs in frantically and says, “I need help.” That's the fun part, you know? I've always loved and enjoyed helping people solve problems.

It just makes you, I think, not only a better employee, but a better human to be able to be diverse and change your plans and help people out. If you have a hard work ethic and you're excited about what you do, there's no limit to the problems we can solve.