A big part of my research happens on the West Antarctic Peninsula, a region of the Southern Ocean that’s one of the fastest-warming places on Earth. The National Science Foundation’s Palmer Station Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program has been running there for over 30 years, cataloguing what’s happening to this really quickly-changing ecosystem.

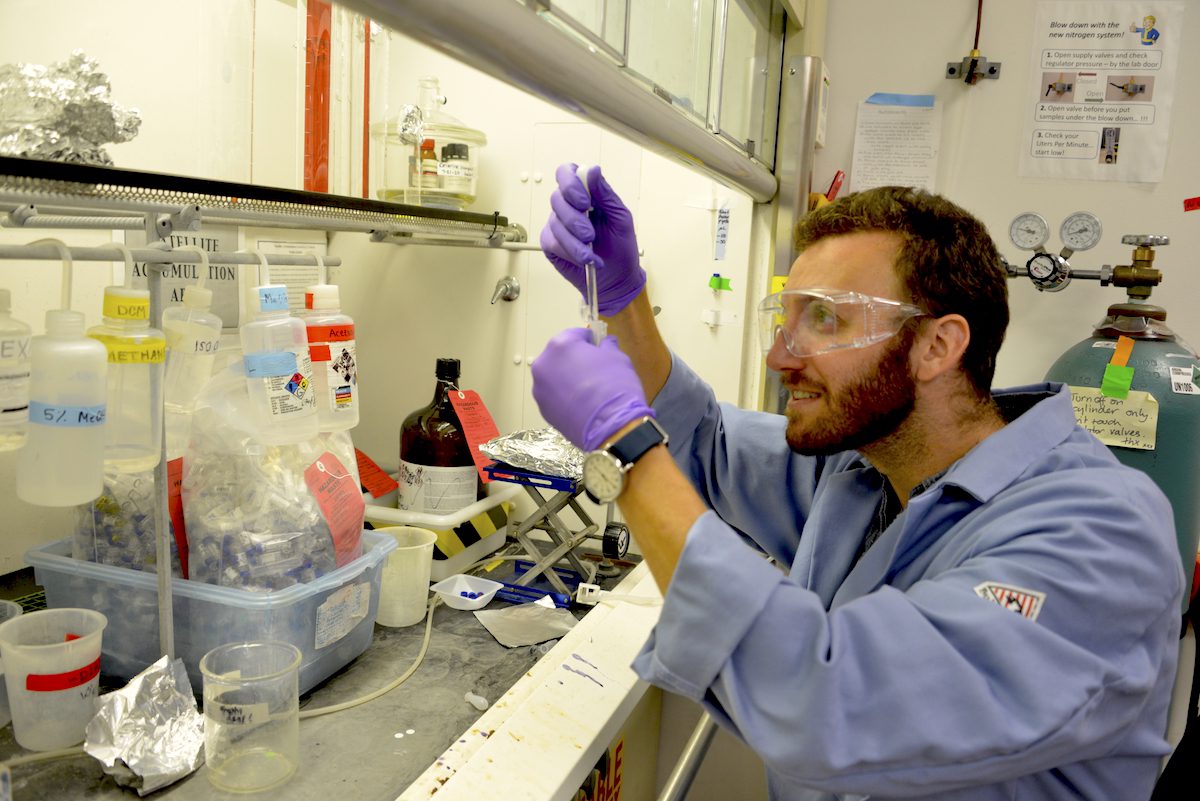

I’ve been to Palmer Station three times, from six weeks to six months. Most of my job down there is filtering lots of water samples to bring back and analyze in our lab in Woods Hole. I’m most interested in the stuff in the water that you can’t see, at least without a microscope: the microbes capturing carbon through photosynthesis and releasing it through respiration. In the ocean, they’re the base of the food chain, the base of the carbon cycle. And that’s the aspect that I find most compelling—these processes happening at such a small scale, but with global impact.

Something like 50% of the oxygen on Earth is produced by microbes photosynthesizing in the ocean, and we can’t even see it. But all of the fundamental chemical cycles on Earth are governed by the interacting metabolisms of these unseen little creatures.

I’m trying to understand how the changing light levels throughout the day affect microbial rhythms and energy storage. In most of the ocean, there’s a daily oscillation of energy in phytoplankton because of the solar cycle. They take sunlight and make fats and sugars during the day, then they burn it to rebuild all of their cellular machinery overnight. But when it’s sunny for almost 24 hours, how much carbon and energy are they able to fix? How much fixed carbon will be able to sink down to be sequestered on the sea floor? How much carbon will be available to krill, and then to penguins and whales? Theoretically, if it’s an unchanging ecosystem, you want to establish a baseline to understand things like, “Oh, this is how this ecosystem works.” But at the same time, we’ve got rapid climate change, so it feels even more critical to understand these processes as fast as we can.

I feel incredibly lucky to have been to Antarctica. I think it’s easy to forget when you’re up here in Woods Hole that right at this exact moment, there’s an ocean that either stays sunlit or goes dark for six months at a time, and an entire continent covered in ice. All you see is ice, forever. It’s incredible that that exists on this planet.