Newly Upgraded Alvin Sub Heads for West Coast

May 24, 2013

On Sat., May 25, 2013, the R/V Atlantis will leave Woods Hole carrying the newly upgraded submersible Alvin, marking a major milestone in the sub’s $41 million redesign. Both ship and sub are owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for the benefit of the entire U.S. ocean science community. They are expected to reach Astoria, OR, on June 20.

“This is an important moment in the long process of building the sub and bringing it back online,” said WHOI President and Director Susan Avery. “Alvin is a cornerstone of U.S. deep-ocean research, enabling untold scientific discoveries and greater understanding of our ocean. We’re eager to have it back in service.”

In September, Alvin will undergo the Navy certification process, making a series of progressively deeper dives off Monterey, Calif. Once certified, the sub will be put through its paces in a science verification cruise in Nov., to ensure all of its scientific systems are operational. Alvin is scheduled to return to service in December 2013.

Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and WHOI, the planning process for the sub’s upgrade began over a decade ago. In 2005, work was begun by Southwest Research Institute to design and forge a new titanium personnel sphere, one of the biggest technical challenges in the Alvin upgrade project.

The sphere, which holds a pilot and two scientists, is designed to descend to 6500 meters (21,000 feet or 4 miles) – depths that generate nearly 10,000 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure on the sphere. Construction of the sphere, which has 3-inch-thick walls, required more than 40,000 pounds of titanium. Identical hemispheres were forged and then welded together with an electron beam. Its interior diameter is 4.6 inches wider than Alvin’s previous sphere, increasing the interior volume from 144 to 171 cubic feet. With five viewports, it also has improved and overlapping fields of view for the pilot and scientists allowing for better observations and collaboration in selecting sampling sites.

The personnel sphere underwent hydrostatic pressure testing in June 2012, and was successfully tested to the equivalent of 8000 meters water depth.

Although the new sphere is rated to depths of 6500 meters, the sub’s dives will be limited to 4500 meters until a second phase of the upgrade can be completed. Phase two hinges on the development of improved lithium ion battery technology and funding.

Improvements made to the submersible during the Phase one upgrade include:

- A new, larger personnel sphere with an ergonomic interior designed to improve comfort on long dives

- Five viewports (instead of the current three) to improve visibility and provide overlapping fields of view for the pilot and two observers

- New lighting and high-definition imaging systems

- New syntactic foam providing buoyancy

- Improved command and control system

Additional improvements were needed to the R/V Atlantis to accommodate the larger, heavier sub. Among the ship’s upgrades were a strengthened A-frame, which is used to launch and recover the sub, and alterations of the hangar where the sub is stored when not in use.

“This upgrade has been painstakingly completed by a one-of-a-kind team of engineers, technicians, and pilots at WHOI. The Institution is very proud of their diligence and hard work in devoting themselves to this important project,” said WHOI VP for Marine Facilities and Operations Rob Munier.

The world’s longest-operating deep-sea submersible, Alvin was first launched in 1964. It has made 4,664 dives and played a role in a number of important deep-sea discoveries. Its most famous exploits include locating a lost hydrogen bomb in the Mediterranean Sea in 1966, exploring the first known hydrothermal vent sites in the 1970s, and surveying the wreck of RMS Titanic in 1986. Its final series of dives before the current upgrade period were in the Gulf of Mexico exploring deep-sea biological communities near the site of the Deepwater Horizon blowout and oil spill.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans’ role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.

For Immediate Release

Media Relations Office

media@whoi.edu

(508) 289-3340

Upgraded HOV Alvin was loaded onto R/V Atlantis at the WHOI dock on May 13, 2013. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Upgraded HOV Alvin was loaded onto R/V Atlantis at the WHOI dock on May 13, 2013. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The R/V Atlantis is set to transport newly upgraded HOV Alvin to Oregon through the Panama Canal. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

The R/V Atlantis is set to transport newly upgraded HOV Alvin to Oregon through the Panama Canal. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The upgraded HOV Alvin sphere features five viewports (instead of three) to improve visibility and provide overlapping fields of view for the pilot and two observers. Not pictured here, there are two additional viewports on the sides. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

The upgraded HOV Alvin sphere features five viewports (instead of three) to improve visibility and provide overlapping fields of view for the pilot and two observers. Not pictured here, there are two additional viewports on the sides. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In June 1964, Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin was commissioned on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution dock. The dream of building a human-occupied deep ocean research submersible began eight years earlier, when participants at a symposium in Washington drafted a resolution that the U.S. develop a national program for undersea vehicles. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

In June 1964, Deep Submergence Vehicle Alvin was commissioned on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution dock. The dream of building a human-occupied deep ocean research submersible began eight years earlier, when participants at a symposium in Washington drafted a resolution that the U.S. develop a national program for undersea vehicles. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Alvin and its first tender, the 105-foot catamaran Lulu, which was built in 1965 in Woods Hole using surplus Navy mine sweeping pontoons. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Alvin and its first tender, the 105-foot catamaran Lulu, which was built in 1965 in Woods Hole using surplus Navy mine sweeping pontoons. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Researchers placed instruments in Alvin's basket in the late 1960s prior to the sub's launch. Undersea instruments used by researchers in Alvin became more sophisticated in later years. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Researchers placed instruments in Alvin's basket in the late 1960s prior to the sub's launch. Undersea instruments used by researchers in Alvin became more sophisticated in later years. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Alvin has gone through a major overhaul about every three years to upgrade various components and check safety systems. All of the sub's components have been replaced at least once, so that none of the original Alvin remains. (©Terri Corbett, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Alvin has gone through a major overhaul about every three years to upgrade various components and check safety systems. All of the sub's components have been replaced at least once, so that none of the original Alvin remains. (©Terri Corbett, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The research vessel Atlantis II, owned by the National Science Foundation, joined the WHOI fleet in 1963. It cruised over one million miles as both a general-purpose research ship and as a tender for Alvin from 1983 until the ship's retirement in 1996. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

The research vessel Atlantis II, owned by the National Science Foundation, joined the WHOI fleet in 1963. It cruised over one million miles as both a general-purpose research ship and as a tender for Alvin from 1983 until the ship's retirement in 1996. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

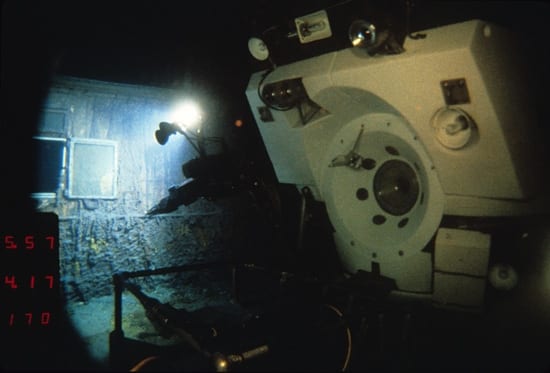

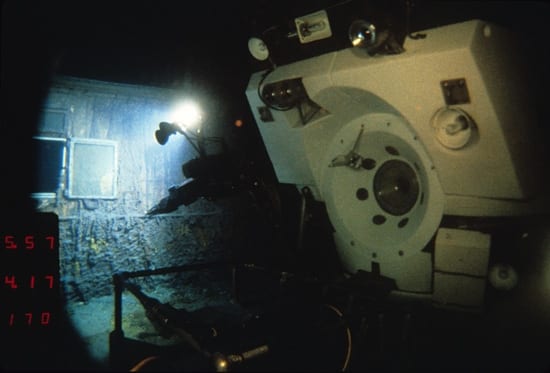

Media interest in Alvin boomed in 1986 after the wreck of the Titanic was found and researchers used the sub to test the capabilities of a remotely operated vehicle called Jason Jr (positioned here inside the sub's basket). (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Media interest in Alvin boomed in 1986 after the wreck of the Titanic was found and researchers used the sub to test the capabilities of a remotely operated vehicle called Jason Jr (positioned here inside the sub's basket). (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

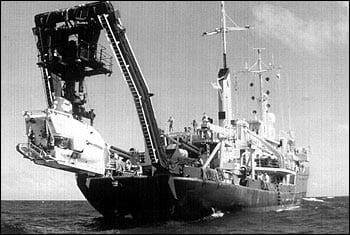

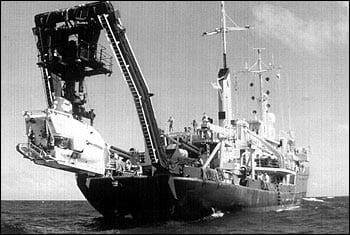

In 1997, the research vessel Atlantis became the support vessel for Alvin, and remains so today. It was the first ship designed to support a range of deep-sea exploration vehicles. The A-frame for submersible handling is visible on the stern. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

In 1997, the research vessel Atlantis became the support vessel for Alvin, and remains so today. It was the first ship designed to support a range of deep-sea exploration vehicles. The A-frame for submersible handling is visible on the stern. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

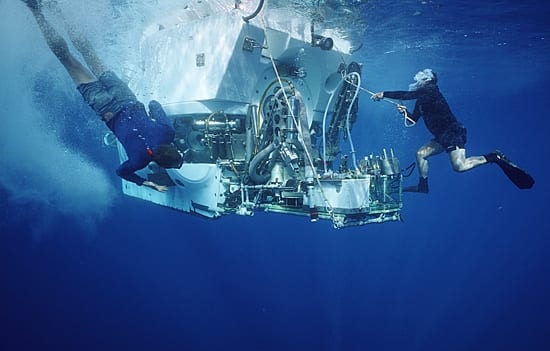

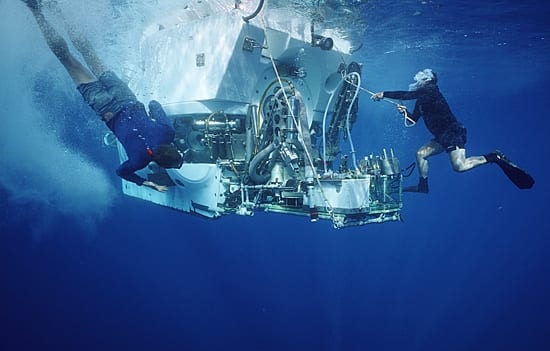

Recovering the sub after a dive takes the support of members of the Alvin group, as well as the ship's crew. (©Craig Dickson, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Recovering the sub after a dive takes the support of members of the Alvin group, as well as the ship's crew. (©Craig Dickson, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

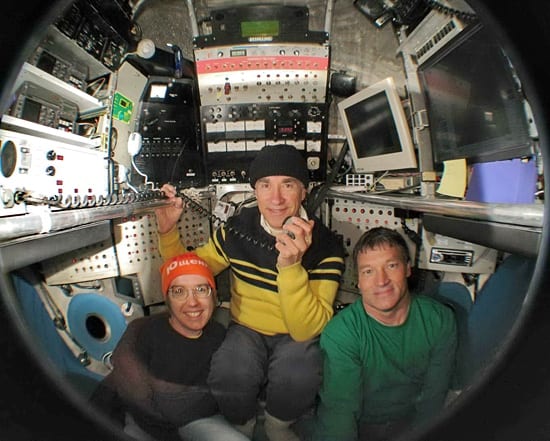

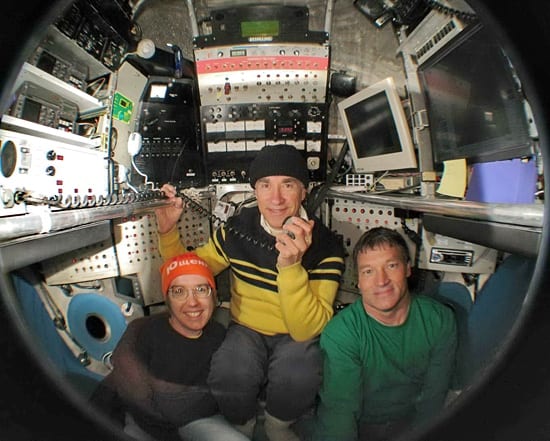

Inside Alvin's titanium sphere, the pilot looks out the forward view port (right) while two scientists observe from side view ports. (©Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Inside Alvin's titanium sphere, the pilot looks out the forward view port (right) while two scientists observe from side view ports. (©Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

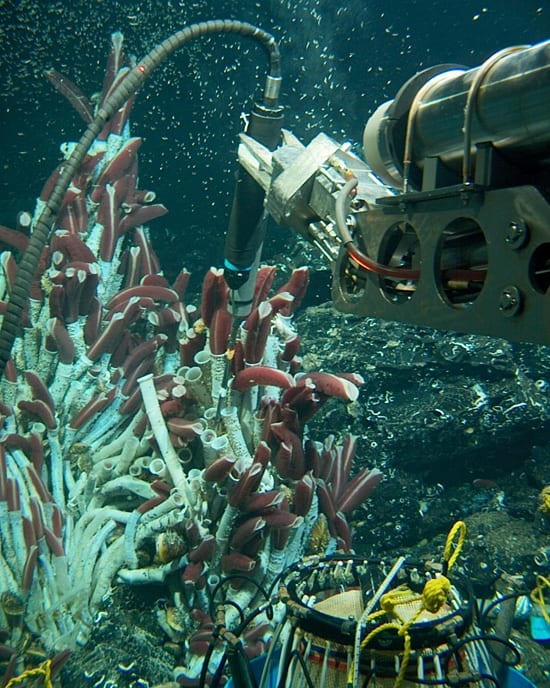

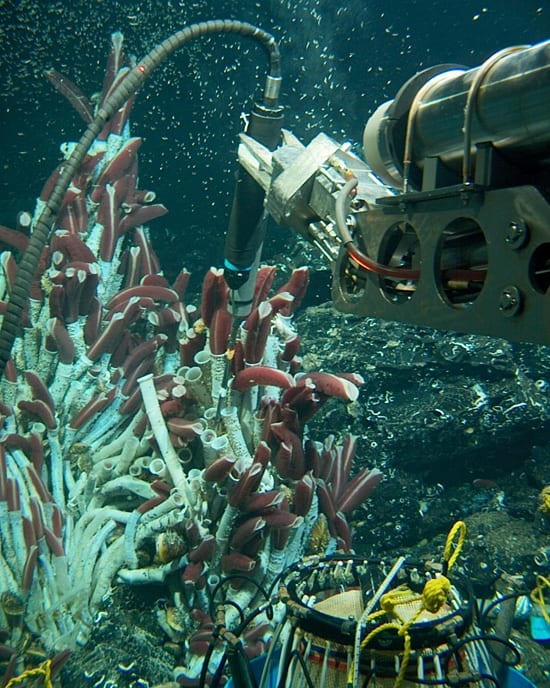

One of the sub's two manipulator arms collects a tubeworm at a hydrothermal vent. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

One of the sub's two manipulator arms collects a tubeworm at a hydrothermal vent. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

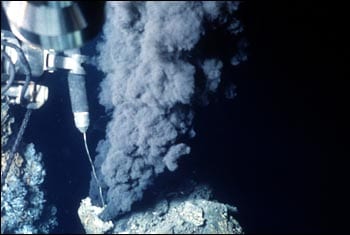

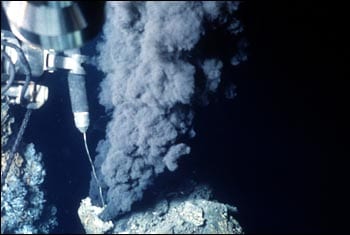

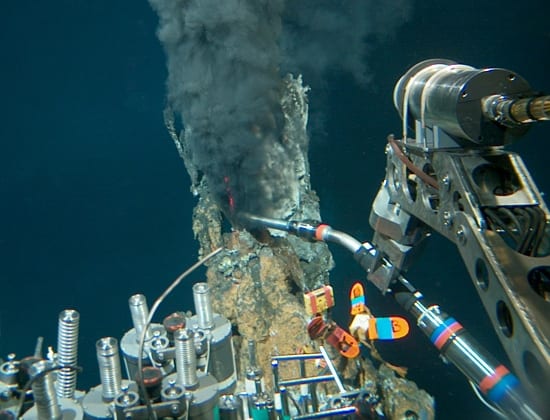

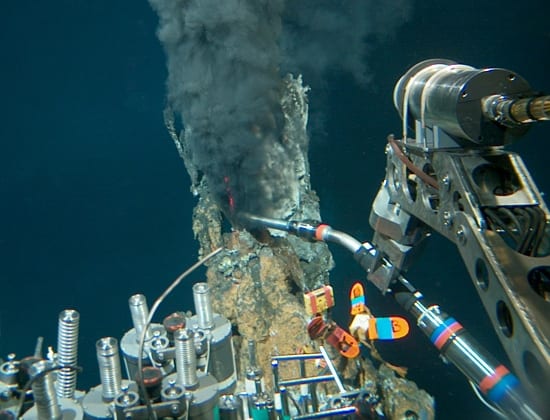

A temperature probe is placed in a black smoker. Researchers in Alvin found the vents spewing superheated fluids in 1979 during a research expedition on the East Pacific Rise south of Baja California. Since then black smokers have been found at many vent sites around the world. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

A temperature probe is placed in a black smoker. Researchers in Alvin found the vents spewing superheated fluids in 1979 during a research expedition on the East Pacific Rise south of Baja California. Since then black smokers have been found at many vent sites around the world. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A remote camera captured this image of Alvin at work on a seafloor hydrothermal vent in the early 1990s. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

A remote camera captured this image of Alvin at work on a seafloor hydrothermal vent in the early 1990s. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The submersible Alvin prepares for a dive in September 2009. Built in 1964, the hardworking sub helped turn a sunless, freezing marine world into a new frontier. More than 4,000 dives to the seafloor have allowed scientists to discover hydrothermal vents, deep-sea minerals, and hundreds of previously unknown organisms. (Photo by Rod Catanach, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

The submersible Alvin prepares for a dive in September 2009. Built in 1964, the hardworking sub helped turn a sunless, freezing marine world into a new frontier. More than 4,000 dives to the seafloor have allowed scientists to discover hydrothermal vents, deep-sea minerals, and hundreds of previously unknown organisms. (Photo by Rod Catanach, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In over 41 years of operation, the submersible Alvin has logged more than 4,300 dives and 30,000 hours exploring the deep ocean, diving a combined total of more than 9 million meters along the way. (Bill Lange, Tim Shank, and the Alvin Group, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

In over 41 years of operation, the submersible Alvin has logged more than 4,300 dives and 30,000 hours exploring the deep ocean, diving a combined total of more than 9 million meters along the way. (Bill Lange, Tim Shank, and the Alvin Group, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Sweaters and knit hats are typical clothing for scientists and a pilot traveling in the submersible Alvin. Temperatures in the (unheated) submersible drop as the depth increases—in this case, to 1.6 miles depth (2,660 meters) during a September 2007 dive to the Juan de Fuca Ridge offshore Washington and Oregon. "The average temperature outside the submersible is usually around 35°F," said pilot Mark Spear (right). "Inside the sub with all the electronics, and three people's body heat, it maybe gets down to 45 to 50°F. We do have hot coffee, and new this year are nice, fluffy, and cozy fire-resistant fleece blankets! We always take two or three and it resembles a slumber party after the work is done." This dive included doctoral student Katherine Inderbitzen with the University of Miami and scientist Robert Meldrum with the Geological Survey of Canada. (Photo by Mark Spear, Woods Hole Oceanographic Insitution)

News Release Image

Sweaters and knit hats are typical clothing for scientists and a pilot traveling in the submersible Alvin. Temperatures in the (unheated) submersible drop as the depth increases—in this case, to 1.6 miles depth (2,660 meters) during a September 2007 dive to the Juan de Fuca Ridge offshore Washington and Oregon. "The average temperature outside the submersible is usually around 35°F," said pilot Mark Spear (right). "Inside the sub with all the electronics, and three people's body heat, it maybe gets down to 45 to 50°F. We do have hot coffee, and new this year are nice, fluffy, and cozy fire-resistant fleece blankets! We always take two or three and it resembles a slumber party after the work is done." This dive included doctoral student Katherine Inderbitzen with the University of Miami and scientist Robert Meldrum with the Geological Survey of Canada. (Photo by Mark Spear, Woods Hole Oceanographic Insitution)

Working on the deck of the R/V Atlantis, pilots and technicians from the Alvin Group scrubbed the submersible on the East Pacific Rise in December 2006. Dried on salt, grime, and the remains of doomed sea life that hitch rides to the surface leaves Alvin in need of a good washing. Cleaning the white exterior "skins" (removed for washing on deck) is just one item on the exhaustive list of maintenance requirements met by operators of Alvin to keep the submersible safe and working properly for the hundreds of researchers it transports each year to the seafloor. (Photo by Lance Wills, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Working on the deck of the R/V Atlantis, pilots and technicians from the Alvin Group scrubbed the submersible on the East Pacific Rise in December 2006. Dried on salt, grime, and the remains of doomed sea life that hitch rides to the surface leaves Alvin in need of a good washing. Cleaning the white exterior "skins" (removed for washing on deck) is just one item on the exhaustive list of maintenance requirements met by operators of Alvin to keep the submersible safe and working properly for the hundreds of researchers it transports each year to the seafloor. (Photo by Lance Wills, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

pilot on board the Human Occupied Vehicle Alvin uses one of the vehicles two hydraulically-powered robotic arms to probe tube worms on the sea floor of the East Pacific Rise. The arms have clawed "hands" for deploying scientific equipment and collecting marine organisms. They have a maximum extension of 74 inches and can lift up to 150 pounds. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

pilot on board the Human Occupied Vehicle Alvin uses one of the vehicles two hydraulically-powered robotic arms to probe tube worms on the sea floor of the East Pacific Rise. The arms have clawed "hands" for deploying scientific equipment and collecting marine organisms. They have a maximum extension of 74 inches and can lift up to 150 pounds. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

After securing the lifting lines used to recover the human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin back to its support vessel Atlantis, deckhand Ronnie Whims dives back into the ocean. (Photo by Lance Wills, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

After securing the lifting lines used to recover the human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin back to its support vessel Atlantis, deckhand Ronnie Whims dives back into the ocean. (Photo by Lance Wills, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

A mechanical arm on the Alvin submersible reaches out for a sample from a "black smoker" hydrothermal vent along the East Pacific Rise. Black smokers are so named because they can appear as if dark smoke is billowing from them. In fact, the “smoke” is actually iron- and sulfur-rich minerals precipitating from scalding vent waters—as hot as 760°F—meet the icy cold depths.

((Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)

News Release Image

A mechanical arm on the Alvin submersible reaches out for a sample from a "black smoker" hydrothermal vent along the East Pacific Rise. Black smokers are so named because they can appear as if dark smoke is billowing from them. In fact, the “smoke” is actually iron- and sulfur-rich minerals precipitating from scalding vent waters—as hot as 760°F—meet the icy cold depths.

((Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)

WHOI geochemist Jeff Seewald (green shirt) and biologist Stefan Sievert douse NBC "Today Show" host Ann Curry in icy seawater after her first Alvin dive. In addition to the traditional "baptism," other initiation rites include freezing the first-time diver's sneakers or filling them with whipped cream. New Alvin pilots are sometimes soaked in a mud bath after their first dives. On October 18, 2008, Curry joined Seewald and Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott for a National Science Foundation-funded dive to study microbes in the Guaymas Basin. (Photo by Sean Sylva, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

WHOI geochemist Jeff Seewald (green shirt) and biologist Stefan Sievert douse NBC "Today Show" host Ann Curry in icy seawater after her first Alvin dive. In addition to the traditional "baptism," other initiation rites include freezing the first-time diver's sneakers or filling them with whipped cream. New Alvin pilots are sometimes soaked in a mud bath after their first dives. On October 18, 2008, Curry joined Seewald and Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott for a National Science Foundation-funded dive to study microbes in the Guaymas Basin. (Photo by Sean Sylva, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Each dive requires members of the Alvin team to enter the water to check various components and make sure it comes back to the ship safely. (Photo by Rod Catanach, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Each dive requires members of the Alvin team to enter the water to check various components and make sure it comes back to the ship safely. (Photo by Rod Catanach, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Alvin and the support team work from the WHOI-operated research vessel Atlantis, equipped for moving the 17 metric ton (35,200 pound) submersible into and out of the water. Trained divers (members of Alvin's team) assist with the sub's launch and recovery. (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Alvin and the support team work from the WHOI-operated research vessel Atlantis, equipped for moving the 17 metric ton (35,200 pound) submersible into and out of the water. Trained divers (members of Alvin's team) assist with the sub's launch and recovery. (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

It took two weeks for eight members of the Alvin Group to remove thousands of bolts, hoses, panels, and the submersible's 6-foot titanium personnel sphere during a 2006 periodic overhaul in Woods Hole. The six-month overhaul occurs about every three years. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

It took two weeks for eight members of the Alvin Group to remove thousands of bolts, hoses, panels, and the submersible's 6-foot titanium personnel sphere during a 2006 periodic overhaul in Woods Hole. The six-month overhaul occurs about every three years. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

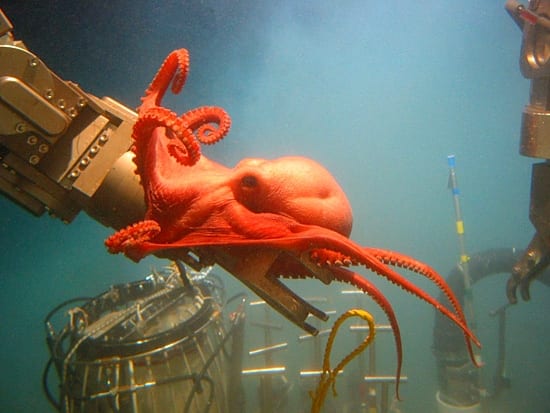

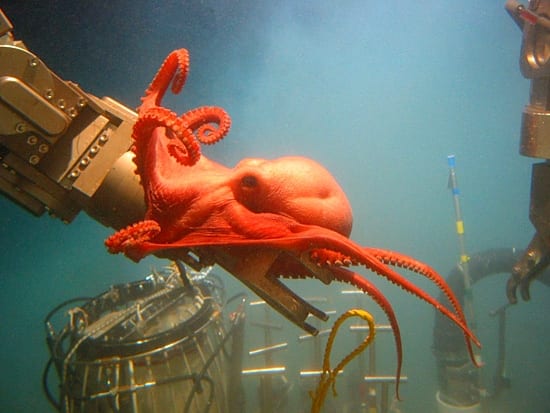

"Most octopuses will let you get close, maybe even touch them, but normally they'll try to run once the manipulator gets close," said Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott, of his encounter with a deep-sea octopus 2,300 meters down (about 7,500 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico. This female was docile and, instead of swimming away, grabbed the submersible's robotic manipulator arm, used for picking up samples of seafloor rocks and organisms.

News Release Image

"Most octopuses will let you get close, maybe even touch them, but normally they'll try to run once the manipulator gets close," said Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott, of his encounter with a deep-sea octopus 2,300 meters down (about 7,500 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico. This female was docile and, instead of swimming away, grabbed the submersible's robotic manipulator arm, used for picking up samples of seafloor rocks and organisms.

When Mark Spear stepped out of the submersible Alvin as WHOI's newest deep-sea pilot, fellow pilot Gavin Eppard greeted him with a traditional baptism on the deck of R/V Atlantis. Spear is the 36th person to complete pilot training in the 42-year history of the submersible. (Photo by Jeremy Potter, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration)

News Release Image

When Mark Spear stepped out of the submersible Alvin as WHOI's newest deep-sea pilot, fellow pilot Gavin Eppard greeted him with a traditional baptism on the deck of R/V Atlantis. Spear is the 36th person to complete pilot training in the 42-year history of the submersible. (Photo by Jeremy Potter, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration)

During the search for a U.S. hydrogen bomb lost in the Mediterranean off Spain in 1966, the Human Occupied Vehicle Alvin operated from a Navy dock landing ship. The red beret was adopted as a badge of camaraderie by the Alvin group during its early years after pilot Val Wilson, originally hired as skipper for Lulu, came back from a trip to the Bahamas sporting one. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)

News Release Image

During the search for a U.S. hydrogen bomb lost in the Mediterranean off Spain in 1966, the Human Occupied Vehicle Alvin operated from a Navy dock landing ship. The red beret was adopted as a badge of camaraderie by the Alvin group during its early years after pilot Val Wilson, originally hired as skipper for Lulu, came back from a trip to the Bahamas sporting one. (Photo courtesy of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Archives)

Graduate students Sigrid Katz (University of Vienna) and Carly Strasser (WHOI) greet Alvin pilot Pat Hickey after he completed his 600th dive in the submersible on November 12, 2006. Hickey has now made more dives than any pilot in the sub's four-decade history. Hickey and fellow pilot Dudley Foster (recently retired) have made more than one-quarter of all of Alvin dives. (Photo by Lauren Mullineaux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

Graduate students Sigrid Katz (University of Vienna) and Carly Strasser (WHOI) greet Alvin pilot Pat Hickey after he completed his 600th dive in the submersible on November 12, 2006. Hickey has now made more dives than any pilot in the sub's four-decade history. Hickey and fellow pilot Dudley Foster (recently retired) have made more than one-quarter of all of Alvin dives. (Photo by Lauren Mullineaux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

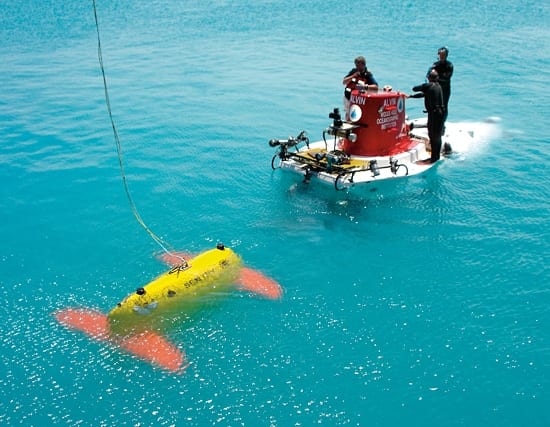

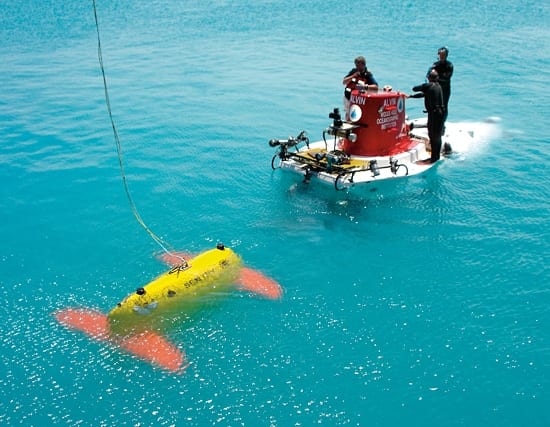

The new Sentry autonomous underwater vehicle meets the submersible Alvin during a testing expedition off Bermuda in April 2006. Sentry is a robotic underwater vehicle used for exploring the deep ocean; it will often be used to complement Alvin by surveying large swaths of ocean floor to determine the best spots for close-up exploration. Sentry is slated to join the National Deep Submergence Facility in 2008. (Photo by Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

The new Sentry autonomous underwater vehicle meets the submersible Alvin during a testing expedition off Bermuda in April 2006. Sentry is a robotic underwater vehicle used for exploring the deep ocean; it will often be used to complement Alvin by surveying large swaths of ocean floor to determine the best spots for close-up exploration. Sentry is slated to join the National Deep Submergence Facility in 2008. (Photo by Chris German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

he wreckage of RMS Titanic was discovered on the seafloor 25 years ago this week. A year later, a WHOI-led expedition returned with the deep-sea vehicle Alvin and Jason Jr., a prototype robotic vehicle tethered to Alvin via a 60-meter fiber-optic cable and equipped with lights and cameras. WHOI scientist Bob Ballard called it “the floating eyeball.” J.J. photographed Alvin pulling alongside Titanic. "The biggest danger to any dive on Alvin is entanglement on the bottom," wrote former Alvin pilot Will Sellers in a memoir. "If I were to get us stuck and was unable to free the sub, we would become a bit of Titanic history ourselves." (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

he wreckage of RMS Titanic was discovered on the seafloor 25 years ago this week. A year later, a WHOI-led expedition returned with the deep-sea vehicle Alvin and Jason Jr., a prototype robotic vehicle tethered to Alvin via a 60-meter fiber-optic cable and equipped with lights and cameras. WHOI scientist Bob Ballard called it “the floating eyeball.” J.J. photographed Alvin pulling alongside Titanic. "The biggest danger to any dive on Alvin is entanglement on the bottom," wrote former Alvin pilot Will Sellers in a memoir. "If I were to get us stuck and was unable to free the sub, we would become a bit of Titanic history ourselves." (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

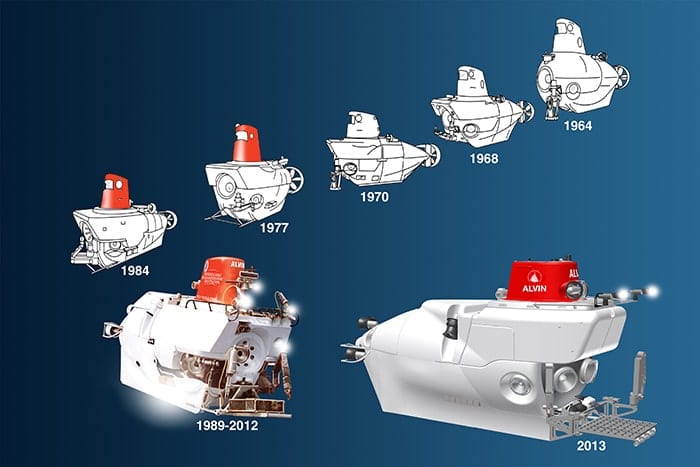

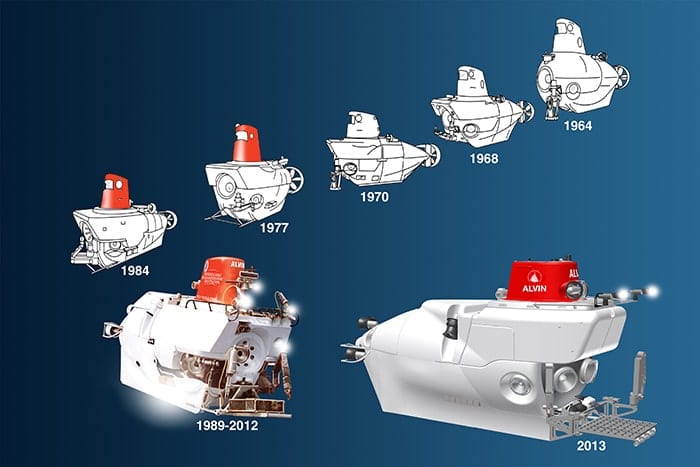

In forty years of operation, the deep submergence vehicle Alvin has evolved and changed its look several times (oldest version at the top right, current version at bottom left, and a future conception of the next Alvin vehicle at the bottom right). In fact, the sub has been completely disassembled every three to five years so engineers can inspect every last bolt, filter, pump, valve, circuit, tube, wire, light, and battery—all of which have been replaced at least once in the sub's lifetime. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

News Release Image

In forty years of operation, the deep submergence vehicle Alvin has evolved and changed its look several times (oldest version at the top right, current version at bottom left, and a future conception of the next Alvin vehicle at the bottom right). In fact, the sub has been completely disassembled every three to five years so engineers can inspect every last bolt, filter, pump, valve, circuit, tube, wire, light, and battery—all of which have been replaced at least once in the sub's lifetime. (Illustration by E. Paul Oberlander, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

See Also

- Alvin Upgrade

- Rebuilding Alvin: Loral O’Hara

A series in Oceanus on the people reassembling the iconic sub - Pressure Testing of New Alvin Personnel Sphere Successful