Give Reefs a Chance » 7 Essential Reef Species

7 essential reef species

Healthy coral reefs are magnets for marine life, rivaling only rainforests for the World’s Most Biodiverse crown. They’re oases in the food deserts of the tropics and the deep, frigid ocean. Up to one-third of all marine species spend at least part of their lives on tropical reefs due to the nourishment and shelter corals provide. They’re nurseries for countless juvenile fish and crustaceans.

The benefits extend to those of us on land. Worldwide, millions of people get food, protection, or income from coral reefs. That’s why it’s so important to give reefs a chance: life as we know it is at stake.

Get to know some of the characters that rely on reefs–and that reefs rely on as well.

1Sharks

A balance of predators and prey ensures enough resources for everyone who call the reef home. Though the label “apex predator” doesn’t apply to all sharks passing through a reef, large species like hammerheads and tiger sharks take the top spot in the food chain since they eat smaller “mesopredators” like the whitetip reef shark. Reef sharks (and big fish like grouper) chow down on the mid-sized fish that might otherwise eat too many of the small fish that keep algae in check, or that prey on filter-feeding shellfish. Some sharks even eat (and definitely scare) sea turtles that feed on seagrass, preventing them from destroying too much of this vital habitat. Sharks also fill an important role because they eat whatever prey is abundant, and remove sick or weakened fish from the ecosystem. In exchange, they enjoy reef “cleaning stations” (symbiotic fishes like wrasse that clean their teeth and skin) and safe hiding places to rest and nurture their young.

2Parrotfish

If you’ve ever basked on a fine white sandy beach in a tropical paradise, you have parrotfish to thank. This bright blue and yellow fish uses its beak-like mouth and 1,000 super-strong teeth to chomp down on algae blanketing coral. Over the course of a year, one parrotfish can process (ahem, poop out) 1,000 pounds (450 kg) of coral sand!

That might sound like a bad thing, but in fact, parrotfish are doing corals a favor by consuming the algae that can choke them out if left unchecked. They’re clearly putting away some coral too, but in reefs where parrotfish proliferate, the coral is much healthier than areas that are overfished.

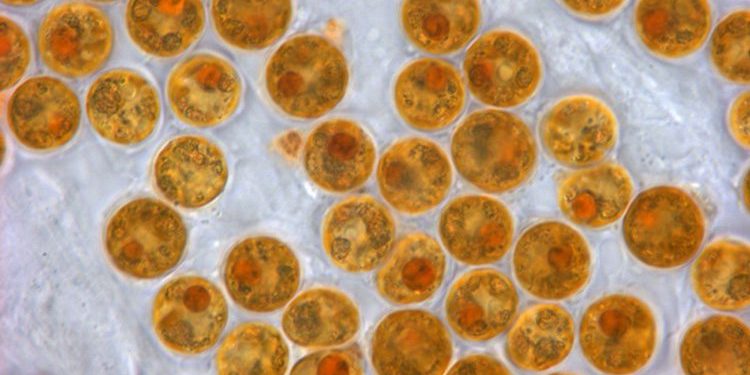

3Zooxanthellae

Despite their tough exterior, corals are actually softies like their anemone and jellyfish cousins. That hard skeleton provides protection–not only for coral polyps, but also for the single-celled algae that lives within them. This algae, a type of dinoflagellate called zooxanthellae (zow-uh-zan-THEH-lai), has enjoyed a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) relationship with coral for about 25 million years. In exchange for free rent and some carbon dioxide, zooxanthellae produce food through photosynthesis, just like plants do on land. And even though coral polyps can grab passing food particles themselves, the algae produce about 90% of the sugars they need.

Zooxanthellae also spruce the place up a bit, lending a greenish-brown chlorophyll tint to the otherwise white coral scaffolding. Some corals also produce a fluorescent pigment that reflects red, orange, or purple instead of green, which protects them from harmful UV rays. But when things get stressful (too hot, too acidic, or not enough oxygen), corals give zooxanthellae the boot. The algae get outta dodge, taking their color with them, a process known as “bleaching.” If water conditions don’t improve, the zooxanthellae won’t come back, and the corals can starve to death.

4Octopus

Though many octopus prefer sandy or rocky bottoms and seagrass meadows, a few species make coral reefs home. The most widespread is the common octopus, whose range extends from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean. In Pacific reefs, the day octopus reigns supreme. These shape-shifting cephalopods are masters of camouflage, blending in seamlessly to the complex, colorful reef bottom structure. Researchers estimate that day octopuses change their skin color and pattern up to 150 times during a four-hour foraging run. They’re just as likely to “walk” on their eight arms as swim, and if danger is near, they’ll use jet propulsion (sometimes with a cloud of black ink) to quickly escape.

Not only are they fascinating to observe, octopuses fill an important role in reef food web. Day octopuses hunt with “parachute attacks,” throwing their web over an area of coral to scare up prey. While the octopus dines on crabs and shellfish, small fish and shrimp come out of hiding, which other fish, like juvenile grouper, quickly snap up. In turn, larger fish, like barracuda and snapper, eat these relatively small octopi.

5Sponges

Sponges are among the oldest marine species in the world, dating back at least 500 million years. They’ve used this time wisely by filling a crucial role as a nutrient recycler. Scientists had long puzzled over how complex reef ecosystems could exist in areas devoid of nutrients, until they figured out the “sponge loop.” Large species can filter hundreds of gallons of water per day, consuming carbon-rich particles as well as carbon dioxide in the process. Snails and other bottom-feeders eat their waste (and benefit from the oxygen they produce), and these life-giving nutrients are thus recycled through the reef food chain. On tropical reefs, sponges recycle as many nutrients as coral and algae combined–and 10 times more than bacteria.

Like coral polyps, sponges need to attach to something hard in order to settle and grow. But unlike coral, they’re able to self-regenerate if damaged. Reaching over three feet (one meter), many tube and vase sponges provide habitat for crabs, shrimp, and small fish. Sponges don’t have many direct predators, but are a favorite snack for some sea turtles.

6Seabirds

When imagining a coral reef, boobies, terns, and shearwaters might not immediately come to mind. But barrier reefs and atolls provide important nesting habitat for sea birds, who return to the same spot to nest year after year. As prolific producers of guano (otherwise known as poop), sea birds also provide an important source of nutrients that spur coral, algae, and sponge productivity. A recent study found that bird-friendly reefs in the Chagos Islands host almost 50% more fish than those infested with egg-eating rats, plus those fish were bigger and consumed three times more algae. Guano might also help with climate resiliency: after mass bleaching events in 2015 and 2016, reef-building coral rebounded much faster in areas where sea birds nest. This slow-release fertilizer nourished newly-settled coral polyps, and the proliferation of herbivorous fish kept competition from algae in check. Efforts to restore sea bird habitat (by removing the rats introduced by humans) might just help save the reefs, too.

7Giant Triton

This enormous sea snail can grow two feet in length, making it one of the biggest molluscs in the world. Found in warm Indo-Pacific and Red Sea coral reefs, giant tritons are voracious predators. Though sea snails aren’t known for speed, the giant triton can easily outpace starfish, sea urchins, and other molluscs. Hunting by night, the sea snail grabs ahold of prey with its muscular foot and incapacitates it with paralyzing saliva. Immune to most biotoxins, the giant triton is especially valued for controlling crown-of-thorns starfish, which eat reef-sustaining coral polyps. Australian scientists estimate that this type of starfish is responsible for half of the coral loss in the Great Barrier Reef, so the giant triton enjoys special protections in Australia and other Pacific island nations.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294582365_Reassessing_the_trophic_role_of_reef_sharks_as_apex_predators_on_coral_reefs

- https://oceanbites.org/coral-reefs-and-sharks/

- https://oceana.org/blog/make-tropical-paradise-start-parrotfish-poop/

- https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/fish/tough-teeth-and-parrotfish-poop

- https://sciencing.com/coral-reefs-come-many-colors-5434662.html

- https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial_corals/coral02_zooxanthellae.html

- https://marinesanctuary.org/blog/coral-reefs-101/

- Octopus, Squid & Cuttlefish. Hanlon et al. 2018, University of Chicago Press.

- https://oceana.org/marine-life/yellow-tube-sponge/

- https://www.coral-reef-info.com/coral-reef-sponges/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-24398394

- https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1241981

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0202-3/

- https://www.anthropocenemagazine.org/2019/07/seabirds-coral-reefs/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20191213145510/https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.14643

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/07/180711131201.htm

- https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/animals/giant-triton

- https://www.americanoceans.org/species/giant-triton/