New ‘Eyes’ Size Up Scallop Populations

The HabCam undersea camera system can help assess seafloor fish stocks

Part of the fun of fishing is never knowing exactly what might be swimming around beneath you. But that mystery is a major annoyance when it comes to keeping track of fish populations.

Now, a new undersea camera is bringing light to the pitch-black depths of New England’s scallop beds. Called HabCam (short for “habitat mapping camera system”), the device was developed by scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) working with Cape Cod scallop fishermen. Fishery managers hope to use the invention to take sharp images of the seafloor and then automatically count and measure scallops on the bottom.

Contrast that with the current technique for monitoring scallop stocks: For 30 days each summer, a research vessel blindly drags an 8-foot-wide dredge across 500 miles (800 kilometers) of ocean bottom, one mile at a time. After shoveling through the catch, measuring the scallops, and estimating how many the dredge left behind, biologists such as Dvora Hart of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) decide on the year’s allowable catch.

The exhausting sampling program works. It’s one reason the U.S. Atlantic scallop fishery has become one of the biggest fisheries in the world and one of a few whose stocks are expanding. Last year’s catch was worth about $400 million, five times the 1998 catch, Hart said.

Draining the water out of the photos

HabCam improves on dredging by adding a 21st-century efficiency: It brings back photos of the seafloor instead of pieces of it. WHOI scientist Scott Gallager and colleagues built a high-resolution camera and four very bright strobe lights—all housed in a 10-foot-long cage of bright-yellow welded pipe. Festooned on every corner with cushions of tire rubber, it’s rugged but hardly streamlined.

“It looks like the roll cage on a double-A fuel dragster,” said Richard Taylor, a retired commercial scallop fisherman and one of Gallager’s collaborators.

A commercial scallop boat, the F/V Kathy Marie, tows the device at about 10 feet (3 meters) above the seafloor, traveling at 3 to 5 knots. Onboard, scientists and fishermen can watch the seafloor go by, 230 feet (70 meters) or more below, as a fiber-optic cable brings camera images back onboard.

Now, instead of shoveling through dredge piles on deck, the HabCam team has to make sense of more than 300,000 images—up to 1,000 gigabytes of data—per day. The individual photos, four to five of them taken per second, must be pieced together into continuous strips, or photomosaics. Then the strips have to be corrected for the way light behaves under water.

At first, even under the flash of the four strobes, images are murky and the colors are washed out. So Norman Vine spends much of his time on image processing.

“I’m trying to pull the plug and drain all the water out of the picture,” he said. Vine is a retired commercial fisherman, lifelong computer hacker, and son of Allyn Vine, the WHOI engineer for whom the deep-diving sub Alvin was named.

When Vine is finished, the images are crisp and bright, as if they were taken from a glass-bottomed boat on a sunny day. Next, a computerized process called segmentation automatically extracts outlines of fish and shellfish from the jumbled background of sand, rock, and seaweed.

A range of advantages

Gallager’s group collaborates with researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory who are developing new ways to segment complicated images. “They consider seafloor images to be a real challenge,” Gallager said. After segmentation, another program classifies the extracted targets into real categories such as scallop, flounder, starfish, and sea grass. That program uses advanced pattern recognition software developed with help from WHOI biometrician Sanjay Tiwari.

HabCam won’t replace dredging altogether, Hart said, because biologists still need to make some actual measurements. But HabCam is easy to use, day or night. It provides 100 percent visual coverage and fine spatial detail (compared with dredges, which miss many scallops and bring up a mile’s worth of catch all at once). HabCam offers real-time images, too, allowing surveyors to double back on interesting areas.

HabCam promises a major advance in scallop monitoring, helping fishery managers judge when they should close or reopen precise portions of the ocean. Next year, when NMFS’ new research ship Henry B. Bigelow goes into service, Hart plans to put HabCam through its paces while making simultaneous dredge runs for comparison. Meanwhile, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game is building a replica of HabCam from Gallager’s specifications to assess its scallop fishery.

Development of HabCam was funded by the scallop industry’s Scallop Research Set-Aside Program. At the end of each scallop season, proceeds from a few final days of fishing are deposited in an account used to fund research. NOAA NMFS supports continuing work on image classification. Test runs using the F/V Kathy Marie were courtesy of owner Arnie DeMello and Capt. Paul Rosonina. Other collaborators include WHOI staff Jonathan Howland, Andrew Girard, Lane Abrams, and Hanu Singh; Cape Cod fisherman Ron Smolowitz; and NMFS biologist Paul Rago.

Slideshow

Slideshow

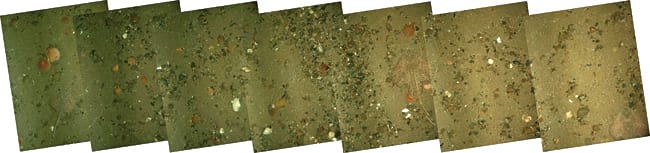

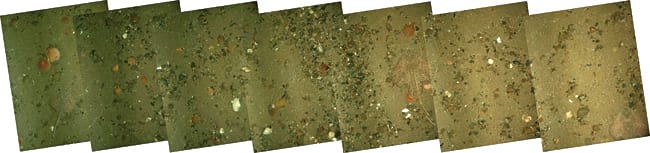

Can you find three skates in this seafloor photomosaic? The images were taken by a newly developed camera system called HabCam, which also can automatically count and measure scallops. (Mosaic by Richard Taylor, courtesy Scott Gallager, WHOI)

Can you find three skates in this seafloor photomosaic? The images were taken by a newly developed camera system called HabCam, which also can automatically count and measure scallops. (Mosaic by Richard Taylor, courtesy Scott Gallager, WHOI)- HabCam (short for ?habitat mapping camera system?) is hoisted aboard the scallop boat Kathy Marie for a test run. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Scott Gallager WHOI Biology Dept.

- Sanjay Tiwari Tiwari worked on HabCam's image analysis software.

- NOAA: Alaska Scallop Fisheries Management