Waves of inspiration

Rachael Talibart explores the infinite creativity of wave photography

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2022

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2022

As a kid, nothing turned Rachael Talibart's stomach faster than sailing. For 12 years, weekend family sails along the British Isles meant the U.K.-based photographer had to become fast friends with the horizon line. There, on that canvas of water, she saw a kaleidoscope of shapes forming, each imbued with the power of her imagination. Now, she's made a career out of capturing the ephemeral beauty of ocean waves on England's Sussex coastline. Her work is featured in esteemed publications like The Guardian and Wired Magazine, as well as in galleries across the U.K. and the U.S. She sat down with Oceanus to discuss her artistic process and the never-ending joys of wave photography.

Oceanus: How did your fascination with seascape photography start?

(© Rachael Talibart)

Rachael: One of my most vivid memories from my childhood was when my family and I got caught out in a storm along the English Channel. It was a lot rougher than I think my dad would've wanted for us. My brother and I were in our oilskins (waterproof jackets), sitting in the cockpit. The boat was heeling right over, because dad insisted on keeping the sails up, and we were being buffeted by enormous wave after enormous wave, with spray coming over us constantly. My brother and I were shrieking with excitement--it was this combined thrill and fear that just made us feel so alive. I think I became fascinated with big waves from that moment on.

In art, there's a long tradition of this relationship with nature, called "the sublime," which inspired many of the Romantic writers in the 1700 and 1800s. It's this idea of terrifying beauty that usually involves humans being overwhelmed by storms, the sea, or enormous mountains. In front of these things, nature dwarfs us and makes us feel puny. But unlike other occasions when we feel small, when nature does the job, it doesn't make us feel miserable. It exhilarates us. I love that.

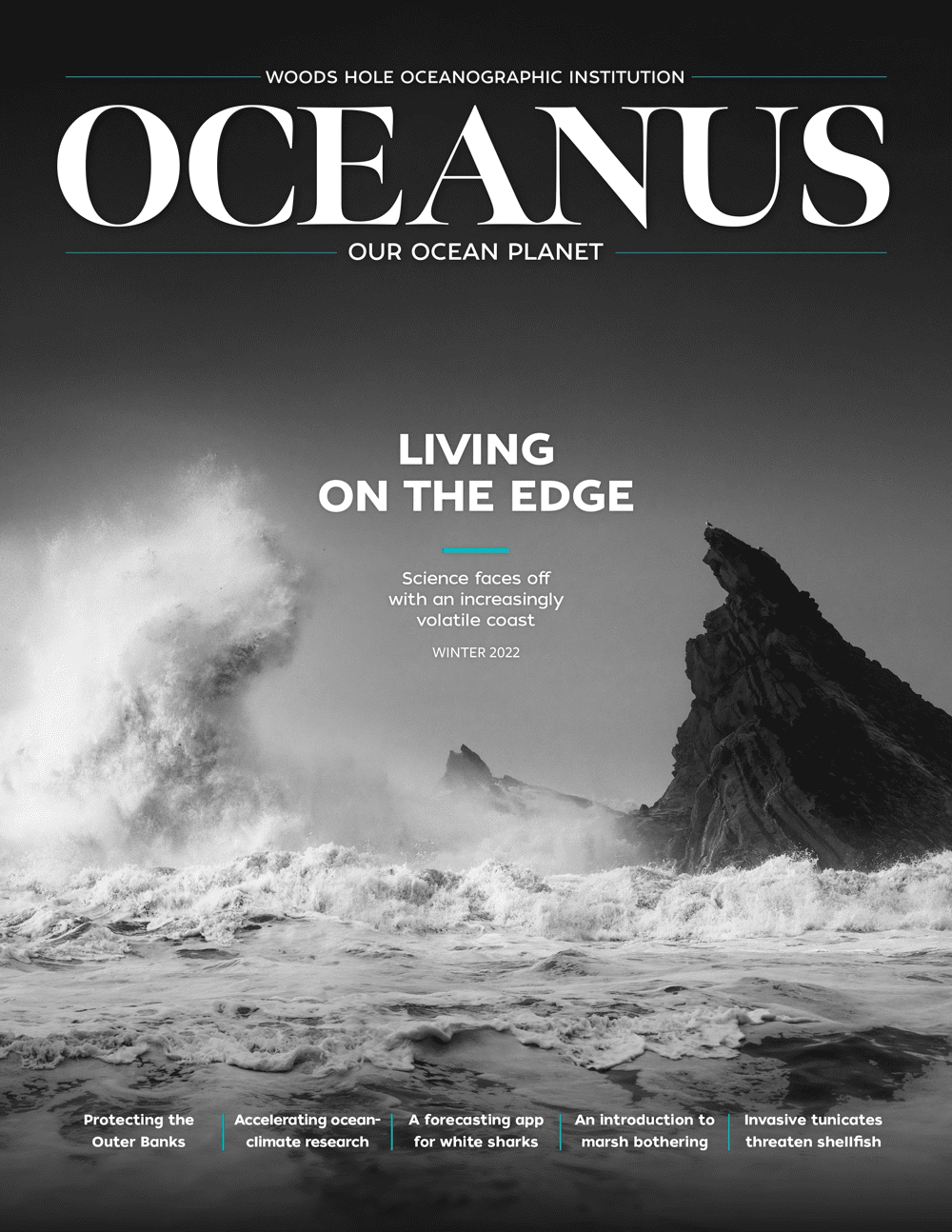

In "The Face-Off," an undeniable tension rages, as the fortress of land faces the unrivaled persistence of the sea. (© Rachael Talibart)

Oceanus: How do you go about capturing these waves?

Rachael: Well, I shoot a variety of things, but for my storm wave photos in particular, I use a 70-200-millimeter lens with a fast shutter speed (so 1,000th of a second, if I can get it). I also don't use a tripod, because the fast shutter is good enough to reduce shake, not to mention that it's too windy to use one in the first place. Typically, I lay down or at least sit, to get as low as possible. That way, the waves stand up more above the horizon where they'll look much bigger. Then, I just watch the sea. What's most important is that I go back to the same locations over and over again. Eventually, I know exactly where to put myself and how certain conditions will impact my photography. There's a lot of serious grunt work going on behind the scenes before the storm even happens. Over days, weeks, months, or even years, I get to know a particular area, so I'm fully empowered to make the most of it when the right moment happens.

Oceanus: In some of your photos, waves seem to have an undeniable face or body. Do you find these waves have a sense of character?

Rachael: Definitely. In a former life, I was a literature graduate student, so I love the classics and have studied Homer extensively. All those wonderful stories from the Odyssey are a huge part of who I am. The concept behind my Sirens Portfolio is that I isolate waves of character that suggest to me some kind of mythological god or creature of the deep. What was important with that work was to not change the shapes that the sea offered when it came time to edit my photos. So those shapes were really there when I captured them. You wouldn't notice them if you were standing on the beach because the sea's moving really fast. But by freezing the action at 1,000th of a second, suddenly you find there are these crazy shapes. I think if you've got any kind of imagination, you can't help but be stirred by what's lurking in the waves.

Oceanus: Do you think of your work as an invitation to people who aren't ocean-goers, who may want a different way to experience the sea?

Rachael: I hope so, I really would like people to know the ocean the way I know it, and realize how life-affirming it is (even if it could kill you in a second). It's so good for our mental health to spend time in the company of something like that. So, spend time with big nature that overwhelms you. It's very rewarding.

Oceanus: What advice would you offer young artists who are interested in photographing the ocean?

Rachael: Good for them, first of all, and long may they continue. The best thing they can possibly do, at least initially, is get off YouTube and take a break from watching photography influencers and tutorials. Of course I'd love for people to watch my content, so I'm not necessarily saying something in my own interest, but it's certainly in theirs: Get out there with a camera. Don't worry too much about the technical rules at first. Just photograph things you really like and then think about how you could make those photographs more interesting. If you stood on a beach with a camera at head height, for example, what would happen if you took that same photo lying down on the sand? Or what would happen if you climbed up a cliff and pointed down at the same thing?

I'll leave you with one of my favorite quotes by Pablo Picasso: "Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working."