Burrows on the beach

Rebuilding after a hurricane isn’t easy—especially for those pale, stalk-eyed creatures known as ghost crabs

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

One day in early September, as a hazy sun came up over Duck, North Carolina, an army stormed the beach. An army of ghost crabs, that is. Hurricane Larry, a Category 3 storm that churned for several days in the open Atlantic before making landfall in Newfoundland, brought powerful waves and storm surge to Duck and other Outer Bank beaches roughly 1,500 miles to the south. And, indirectly, it brought crabs.

"There were tons of crab burrows on the lower beach after the storm," says Britt Raubenheimer, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). "Usually, we see holes on the upper beach, and not nearly so many. It seemed strange."

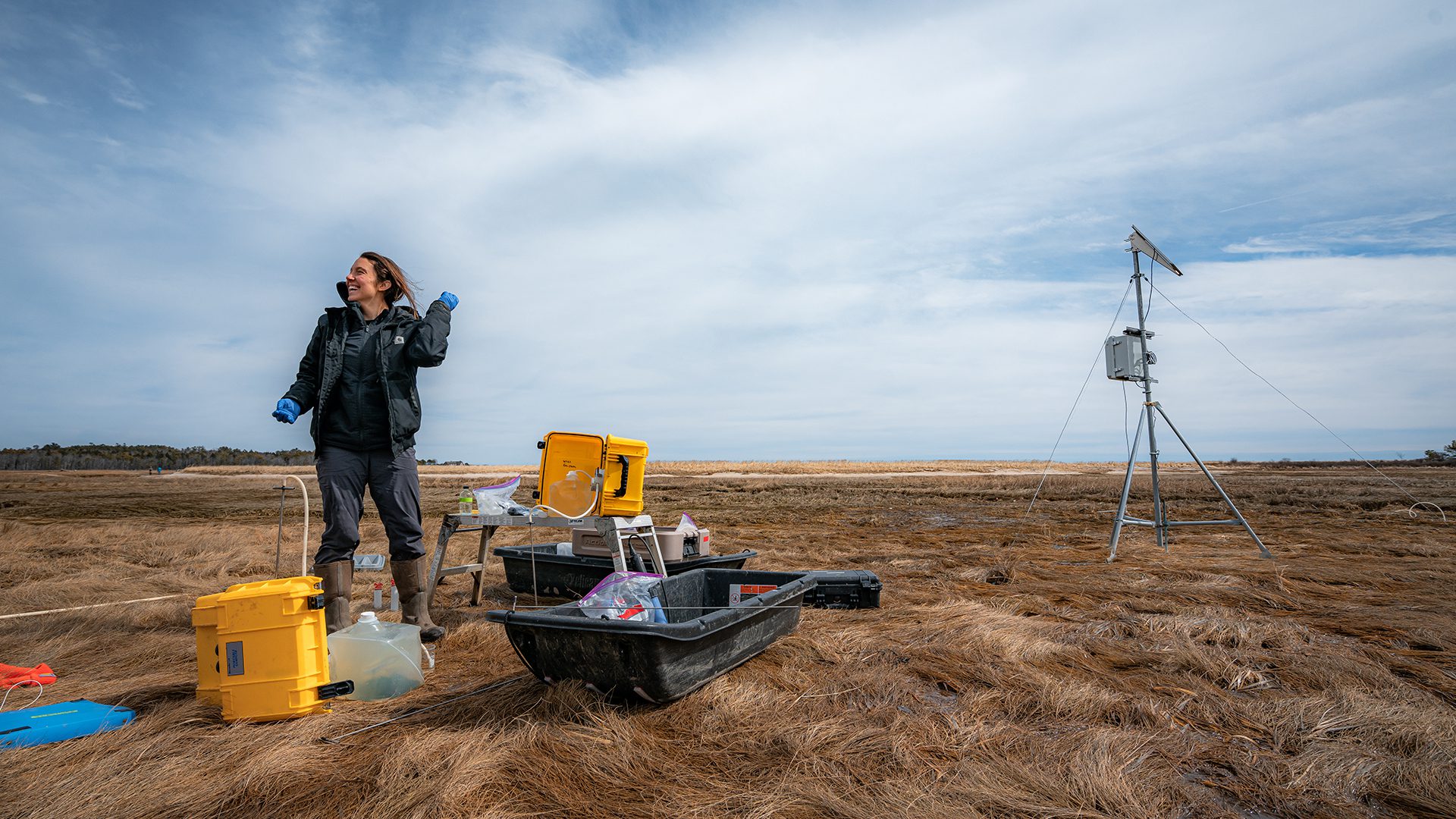

Raubenheimer has been working in Duck with research colleagues from U.S. and international universities and federal agencies on a multi-year field research project across the Outer Banks known as DUNEX. It relies on hundreds of instruments and sensors set up across the beach which collect data before, during, and after major hurricanes like Larry. The idea is, in part, to get a better read on how the ocean affects what happens inland during storms, and vice versa.

"The beach and dunes there act like a sponge that soaks up water from the ocean during big storms," says Raubenheimer. "When this happens, groundwater levels below the dune can rise several feet higher than normal and cause a massive bulge of water that propagates inland."

That bulge, which she likens to a massive underground wave, often leads to flooding along low-lying areas of the Outer Banks. The DUNEX research, she says, can shed light on these processes and ultimately help local communities build resilient strategies to protect their coastline.

Resilience is clearly important for the people who live in a vulnerable, storm-battered area like the Outer Banks. But what about the ghost crabs-those pale, stalk-eyed creatures that came out in droves after the storm? How do they cope after a large storm like Larry?

Crab burrows along a US Army Corps Beach in Duck, North Carolina after Hurricane Larry. (Photo courtesy of Britt Raubenheimer, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The ecological impacts can be substantial, Raubenheimer says, particularly on the burrows that crabs hang out in during the day. After two days of intense waves during the hurricane, the upper part of the beach eroded nearly two feet, while a few feet of sand accreted on the lower beach. "Just that amount of sand movement would damage the burrows, not to mention the flow of water in and out of the beach," she says.

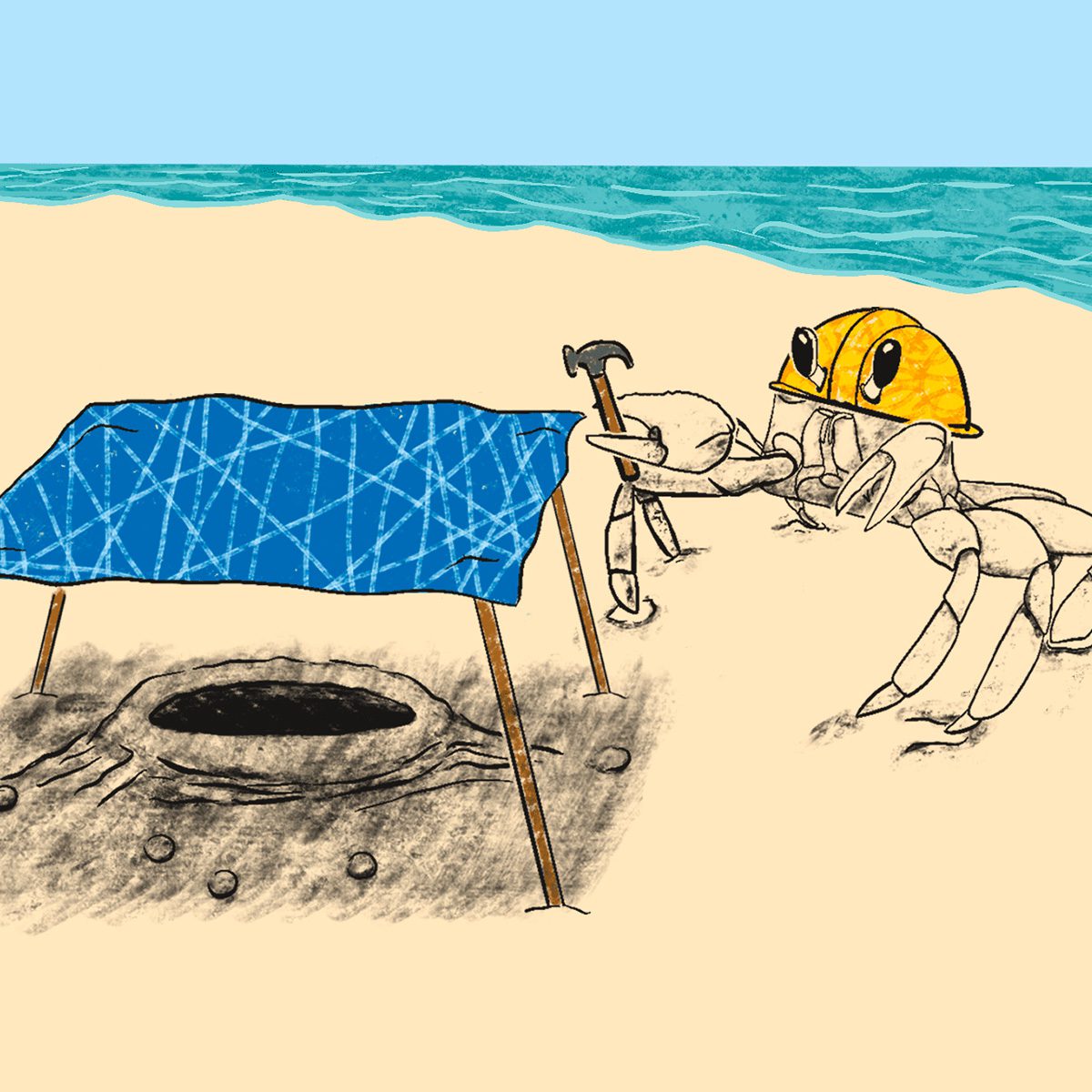

It turns out, the "ghosties" may have had some serious remodeling to do after Larry. Ghost crab burrows, which can run four feet deep, are typically constructed with wet grains of sand-the crabs use it as a substrate to strengthen the tunnels and help prevent collapse. But when damage occurs, the crabs either build new burrows, or try to find their way back into existing ones and make repairs.

Blaine Griffen, a marine ecologist and professor at Brigham Young University, says that in general, the burrows aren't made to last. "Ghost crab burrows are not like those built by other burrowers that are lined by mucus to provide some 'cementing' power and make the burrows somewhat static," says Griffen. "Rather, they are fairly temporary."

To repair an existing burrow, ghost crabs need to haul clawfuls of sand up through the burrow opening. They toss the sand 12-16 inches away from the opening and then smooth out the surrounding surface. Once their underground homes are in tip-top shape again, they crawl back in until nighttime when they head back out to scavenge.

To repair an existing burrow, ghost crabs like the one shown here need to haul clawfuls of sand up through the burrow opening. They toss the sand 12-16 inches away from the opening and then smooth out the surrounding surface. (Photo courtesy of Britt Raubenheimer, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Home repair, however, likely wasn't the only reason for the crabs' coming out party after the hurricane. Studies have shown that their presence can be heavily influenced by human activity on beaches, which is typically interrupted when the weather turns snotty. Fewer people recreating and less off-road vehicle traffic encourages these sand crabs to reclaim their turf.

Additional nutrients, too, may have brought more crabs to the beach after the hurricane. "A few of my colleagues down here suggested that the burrows may have appeared owing to the extra nutrients in the mixing area during and after the storm," says Raubenheimer. When storm surge washes onto the beach and percolates through the sand, she explains, the seawater can bring higher levels of oxygen and nutrients that mixes with the fresh groundwater below. "This may bring more good stuff through the beach and attract smaller crustaceans that are snacks for the ghosties, similar to how opening an inlet to a stagnant pond can attract a whole new ecosystem across the food chain."

While the mystery of the heightened burrowing activity falls outside the scope of the DUNEX research, it has opened some lines of inquiry that Raubenheimer would like to pursue.

"Every study sparks new questions and new ideas," she says. "A crab hole makes a nice open channel for water to flow into and thru the beach, so if there are lots of crab holes, there may be many more open conduits for ocean water to enter the beach."

This, she says, could further enhance the exchange of nutrients, oxygen, and salinity between the ocean and groundwater, and potentially reduce the offshore-flow of waves, leading to even more sand deposits on the beach after big storms.

The DUNEX research is funded by the U.S. Coastal Research Program (USCRP), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), and the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI).