Engineer Par Excellence: Donald Koelsch

A pioneer who helped revolutionize seagoing seismic instruments

Dave Ross should have been sleeping. He was on a research ship in 1975, at sea near the mouth of the Nile. It was 3 a.m., but instead of lying cozy in his bunk, he was on deck in a raging storm. As an oceanographer with seismic instruments in the water worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, he should have been worried, but he wasn’t. He had Don Koelsch at his side.

Koelsch was at work, instructing Ross and others what to do and recovering instruments. On a calm day, recovering several air guns, seismic array, and magnetometer would be tricky work that could take almost an hour. On this night, they didn’t have that kind of time.

“The ship was banging back and forth and waves were crashing over the deck,” Ross, a scientist emeritus at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), recalled. “I remember a wave going up to my waist. We had to tie ourselves down.”

With Koelsch in charge, they somehow managed to get the gear onboard in record time, despite the terrible conditions. Within half an hour, Ross—and his gear—were safely back in the lab.

“It was like in basketball, making the perfect play,” Ross said. “It was our proudest moment. I got goose pimples just now.”

Those who remember the life and work of Donald E. Koelsch won’t be surprised by this story. An electrical engineer with a career spanning more than two decades at WHOI, Koelsch was the ‘go-to’ guy for many scientists needing collaboration, inspiration, and guidance on a variety of seismic instruments and projects, using sound to probe the geology on and below the seafloor. Koelsch’s passing on Jan. 28, 2011, at age 80, inspired an outpouring of stories and memories about the hardworking man.

Seismic pioneer

Underneath his often brusque, New England manner, Koelsch was a patient teacher and a steadfast coworker. Whether he was developing the recording components for the latest ocean bottom hydrophone, detonating TNT off the fantail of a ship, or advising a young scientist on his career path, Koelsch quietly went about his work and got the job done.

“Don … knew how to make things work in the ocean. He had great skills and insights that were just exceptional,” said G. Michael Purdy, a former WHOI geophysicist and now the executive vice president for research at Columbia University. “He did not build things out of rubber bands and paper clips—which was very much the oceanographic tradition. He was interested in building high-quality instrumentation that could be relied upon.”

Together with Purdy, Koelsch revolutionized seismic instrumentation in the 1970s and ‘80s, first by placing hydrophones on the ocean floor, and later, by developing an instrument that could detonate explosive charges just above the ocean floor. Along with engineers Ken Peal, Butch Grant, Jim Broda and others, Koelsch built devices largely from scratch, tweaking and refining them as the technology improved.

“The early instruments … proved to the community that you could do experiments like this,” Purdy said. “It could be a routine thing to record seismic data from the ocean floor.”

Koelsch wasn’t just interested in perfecting an instrument he was working on; he wanted to know the science behind it, too. When designing an instrument or a deployment protocol, he considered every detail. For instance, while working on instrumentation on a seafloor borehole seismic system with WHOI geophysicist Ralph Stephen in the 1980s, Koelsch insisted they install a backup “watch-dog” circuit on a borehole seismometer in case the instrument lost power prematurely. The extra circuitry was a cautious safety measure and not everyone thought the instrument needed it.

Koelsch knew better. He had years of experience working on instruments meant for the ocean environment, first as a senior electronics technician in the Navy; then at the Lamont Geological Laboratory, working under geophysicist John Ewing; and later at Texas A&M, where he finished his master’s degree in electrical engineering. Koelsch had seen his fair share of problems at sea, so he installed the circuit, and they sent the instrument to the bottom.

“Sure enough, we needed that watch-dog circuit,” recalled Stephen. “It would have been an easy thing not to build it, but Don wasn’t that kind of guy. He said, ‘We better have this; something could go wrong.’ ”

Firsthand knowledge, secondhand shirts

Koelsch’s knack for detail was especially important when it came to blowing things up. Over the years, he co-designed the electronics on the Near Ocean Bottom Explosives Launcher (NOBEL), a device that detonated up to 48 charges of TNT at precise times near the seafloor—something that had never been done before.

“There were colossal safety issues in building a device like this,” Purdy said. “When it was fully loaded on the fantail, it had several hundred pounds of TNT. We had to work incredibly close together and be meticulously careful in designing layers of safety. It was a great success.”

Koelsch held himself and his work to high standards and expected his colleagues to do the same. Safety was paramount at sea, and he wasn’t above calling someone on the carpet who had unsafe practices.

“Some people would say he was hard, but you have to appreciate why—he wanted a good job done,” said Butch Grant, a retired WHOI engineer. “If I’m standing on the side of the ship at 3 o’clock in the morning, and I’ve been up for 24 hours … and Don’s standing behind me, I know I can trust him. There’s only a few people you can trust to do that.”

But Koelsch wasn’t all work and no play. At sea, he was famous for his secondhand work shirts, each monogrammed with someone else’s name. Jim, John, Tom, Joe—the shirts could have any name but “Don.” Koelsch’s extra “names” would even make it onto some chief scientists’ cruise reports. “We all played the game, ‘Who are you today? ” remembers Jim Broda, a research specialist in the Department of Geology and Geophysics at WHOI. “He was a wonderful shipmate; he knew so much, he would surprise you. He always had a ready smile.”

Over the years, Koelsch also became known for his patient teaching and sound advice to young engineers and scientists beginning their careers at WHOI. His “road maps” were well-thought-out plans young scientists could use to navigate through their starting years. “He taught [them] to take care of the details, especially for the younger guys who are sometimes impulsive and don’t want to put the time in,” Stephen said.

A legacy at sea and ashore

At their home in Hanover, Mass., Koelsch and his wife Josephine raised four children and always had dogs. He held his two daughters and two sons to the same high standards he had for himself. “It always was, ‘I’ll show you, then you do it,’ ” Josephine, his wife of 55 years said. “Don always had a great faith in his family; [it was] ‘You do what you have to do.’ ”

Today, their home is filled with reminders of his life and work. His office wall is covered with photos of projects and accomplishments. Two Windsor chairs he built with his sons sit on display in the dining room, while his last project, a beautiful Morris chair, graces the sunroom. In the kitchen, a whiteboard covered with phone numbers is an updated version of the blackboard Koelsch used to help his kids with homework while they were growing up.

“He was very proud of all of us,” said his son, Chris, a chemical engineer. “You’ll find all his children are pretty driven also. We owe a lot of that to our mom and dad.”

Koelsch retired in 1995, after 24 years at WHOI. His legacy of pioneering ocean bottom instruments is evident today; seismographs designed specifically for the deep ocean, many of them descendents of instruments he developed, are available to scientists nationwide through the Ocean Bottom Seismograph Instrument Pool.

“The business of electronics is a lifelong study—you have to work at getting all the details right,” said Ken Peal, an engineer in the WHOI Department of Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering, who worked with Koelsch. “People like Don, who are successful, are the ones who welcome challenges and take some chances.”

Special thanks to all those who offered their memories and stories of Don, including: Josephine and Chris Koelsch, Ralph Stephen, Mike Purdy, Jim Broda, Ken Peal, Keith von der Heyt, Dave Ross, Butch Grant, and Dave Dubois. The Koelsch family asks that donations in Don’s memory be sent to Norwell VNA Hospice, 91 Longwater Circle, Norwell, Mass. 02061.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Don Koelsch prepares an instrument for deployment as part of the Low Frequency Acoustic Seismic Experiment. The instrument was designed to record seismic data for several months while stationed within a borehole drilled in the seafloor. (Photo courtesy of Josephine Koelsch)

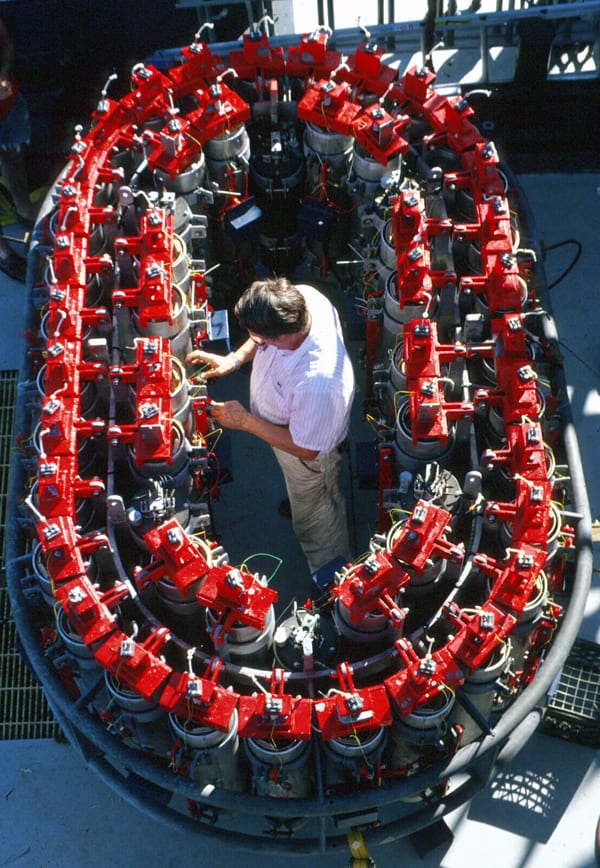

- Don Koelsch checks the electronics on the Near Ocean Bottom Explosives Launcher (NOBEL) on the research vessel Atlantis II in the 1990s. Koelsch helped develop NOBEL, which was the first system to successfully detonate multiple high-explosive charges at full ocean depths. Energy generated by the explosions could be detected by an array of seismometers, allowing geologists to glimpse the structure of Earth's crust beneath the seafloor. (Photo by James Broda, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

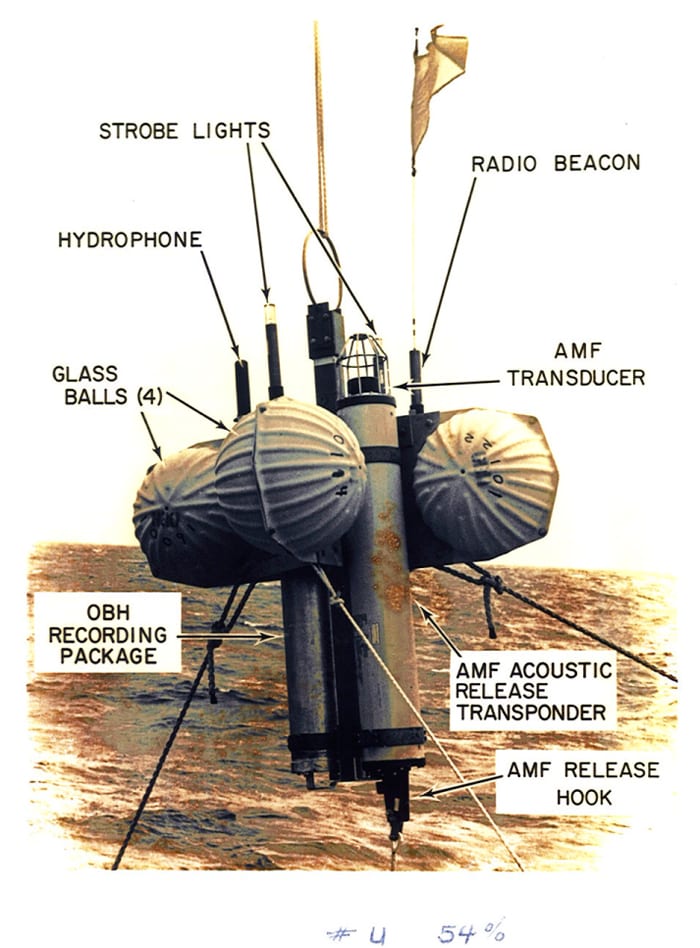

- Photoillustration of a seafloor hydrophone Don Koelsch helped design. The hydrophone detected and recorded sound waves generated by explosive charges set off near the seafloor. As the sound waves traveled through layers of sediment and crust, their strength and direction were affected by the structure of the layers they passed through. (Photo illustration courtesy of G. Michael Purdy, Columbia University)

- Don Koelsch (left) and other WHOI engineers and seismologists with the Near Ocean Bottom Explosives Launcher (NOBEL) system on the fantail of research vessel Atlantis II in 1991. On this cruise, they deployed the NOBEL system along the East Pacific Rise to gain understanding of how new crust forms on the seafloor. Also pictured (l to r, from Koelsch): MIT graduate student John Olson, WHOI research assistant Rob Handy, University of Hawaii scientist Gerard Fryer, and WHOI research associates Jim Broda and Beecher Wooding. (Photo by Dave DuBois, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- An Oceanographer’s Atlas

- A cozy crusade

- 5 WHOI women making waves in ocean science and engineering

- Five idioms for ocean lovers

- Accessible Oceans

- Diverse Voices From Our Maritime Past

- Five books WHOI researchers are reading right now

- On the high seas

- Future Voices: how kids view our ocean in the coming decades