Diverse Voices From Our Maritime Past

Exploring the value of historical observations by mariners of color

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

WHOI biologist and veterinarian Michael Moore has studied the North Atlantic right whale for twenty-five years. Regularly working to monitor the populations of these critically endangered animals and to help free individuals from entanglements in fishing gear, Moore is often out at sea directly beside the animals. Yet in his new book We Are All Whalers: The Plight of Whales and Our Responsibility (2021), he takes his reader far from the range of this species to the Pacific Arctic, to Utqiagvik, Alaska, to visit with Iñupiaq whale hunters and learn from their traditional knowledge of bowhead whale biology. Moore listened to audio recordings of whaling captains compiled and collected as part of Project Jukebox, a digital archive of oral histories, maps, and texts curated by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Oral History Program.

"Unless we listen to the information and history from people of all the relevant cultures and societies," Moore says, "we will not understand how each species came to its current status in terms of distribution, abundance, and habitat."

WHOI biologist Michael Moore at Rock Harbor, Orleans, Massachusetts. (Photo by Matt Barton, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

By providing access to local and marginalized voices, these archives hope to help ensure that local communities can benefit from the work of Western scientists and historians. Websites such as Project Jukebox require decades of careful curation, thoughtful data-marking, and thorough descriptions to make these sites searchable in varied ways, helping researchers construct large-scale environmental histories of individual marine species, groups of species, or even ecosystems.

Environmental historians, marine ecologists, and other scholars ask questions that are quantitative-how much sea grass here in the 1700s; how many bowheads there in the 1900s. And, they pose qualitative questions about perceptions of marine life-how did mariners respond to seeing a shark here in the 1600s; how did local fishermen value shearwaters there in the 1800s?

The answers to these questions require the study of historical marine observations by a diverse range of observers, including Indigenous peoples and marginalized mariners, fishermen, and naturalists. Including these records in undergraduate and graduate coursework also decolonizes syllabi, clarifying that it has not only been white Western men who have built our global knowledge of ocean life. And researchers studying diverse sources help reduce biases in their data and the studies themselves.

Re-examining neglected narratives

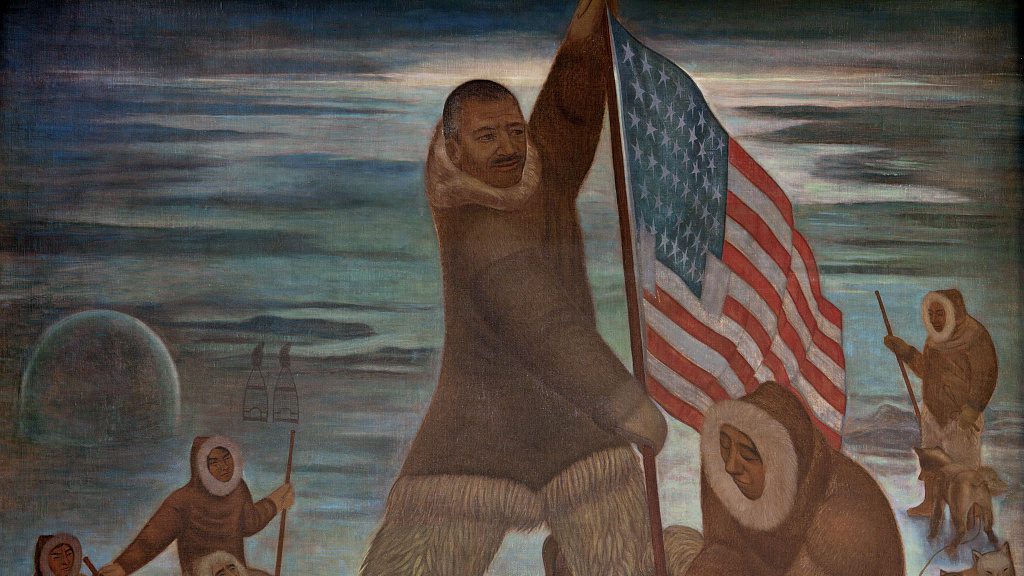

Consider, for example, the narrative of the Black polar explorer Matthew Henson. He started his career at sea as an orphaned cabin boy on a ship bound from Baltimore to China. By 1908, at the age of thirty-seven, he was serving as Commander Robert Peary's right-hand man for their seventh and final high Arctic expedition. Henson by then was a gifted carpenter, sailor, logistics manager, and hunter. He was fluent in the Inuktitut language and respected by both the Inuit and the American crewmembers as the expedition's most-skilled sled driver and dog handler.

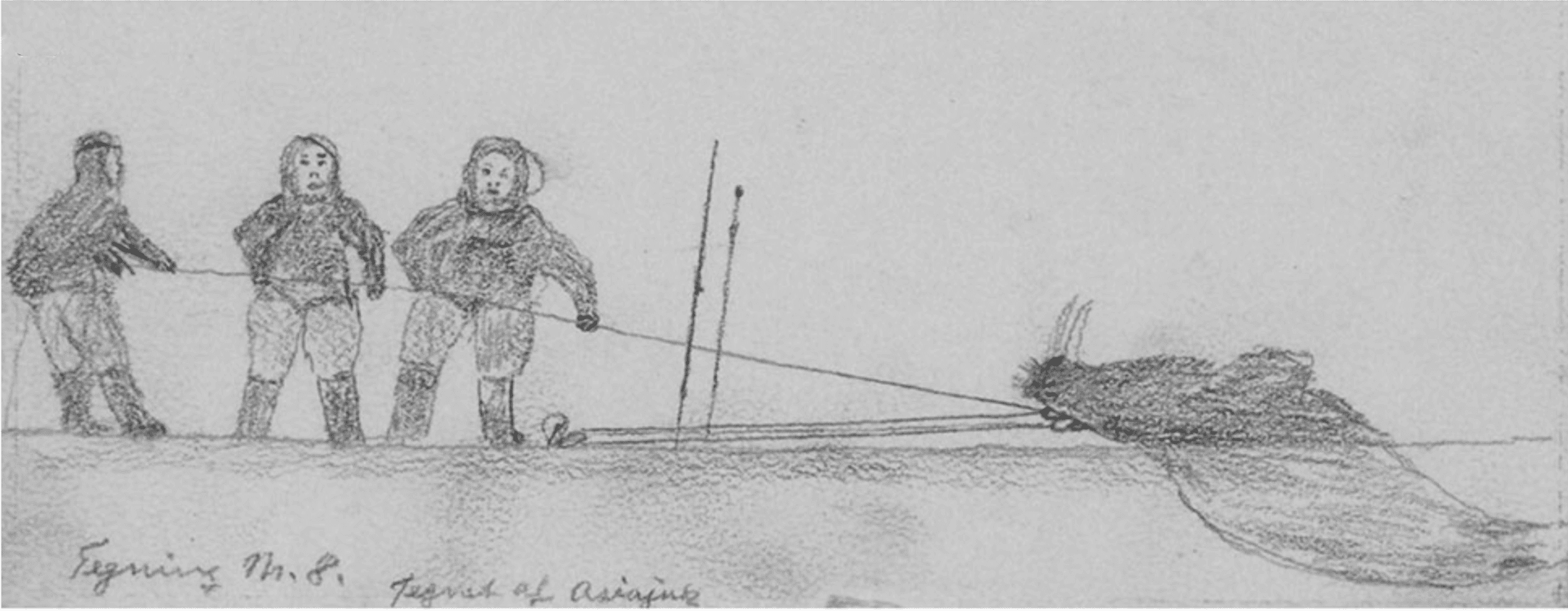

En route to their winter camp aboard the Roosevelt, steaming through Ikeq-Smith Sound, Henson and his shipmates hunted for walrus meat to trade with the Inuit and to fortify their dogs for the long winter camp. Henson led the hunt, primarily by killing walruses in the water with a rifle from a small boat. They hunted for several days.

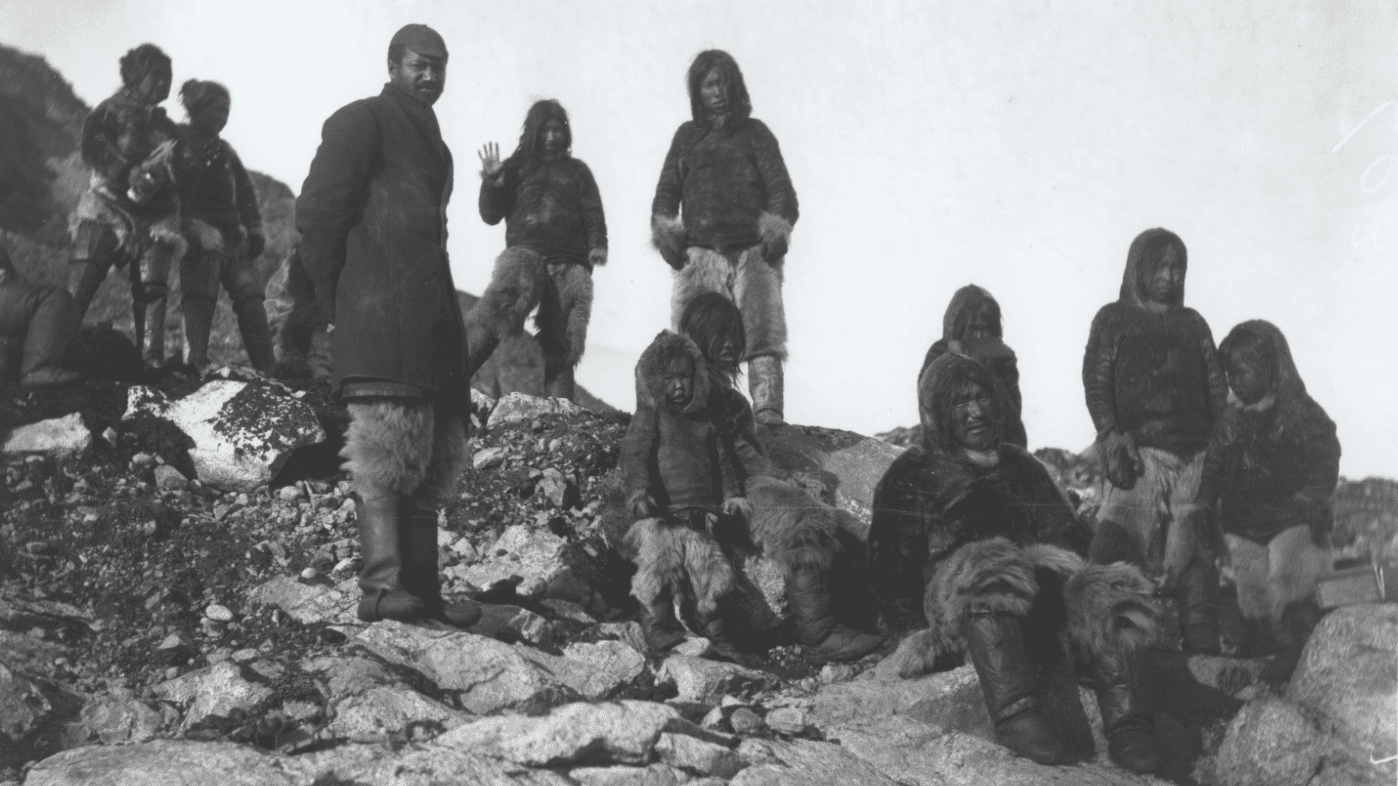

In his narrative of the expedition, Henson left several useful observations about populations of walruses and other marine mammals. This was particularly true in relation to the dwindling tribe of Inughuit people living in the far northwest of Greenland, four of whom helped Peary and Henson on the final sledge to the location they believed to be the North Pole. Although he and his shipmates killed at least 70 walrus themselves over the course of their entire trip, Henson wrote the following in his narrative A Negro Explorer at the Pole (1912): "It is sad to think of the fate of my friends who live in what was once a land of plenty, but which is, through the greed of the commercial hunter, becoming a land of frigid desolation. The seals are practically gone, and the walrus are being quickly exterminated."

Matthew Henson standing with a group of Inughuit people,1892-94 (Photo courtesy of The Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College)

Henson is far from the first visiting mariner to record colonial devastation on marine populations and its impact on Indigenous peoples. But Henson's comments are exceptional because the more widely-read parallel accounts of the same American polar expeditions as written, for example, by Commander Peary and Peary's wife, Josephine Diebitsch Peary, include almost no comments on marine mammal depletion or its impact on the local people. These observers instead celebrated how their style of killing with firearms and harpoons from whaleboats was far more effective than the Indigenous methods conducted from the edges of the ice.

In this way, Matthew Henson's observations of the far northern Arctic marine environment are useful as one crucial data point for modern environmental historians, conservation biologists, resource managers, and ecologists of the region who try to reconstruct past populations, relationships, and marine animal behaviors. "The Eskimos themselves now hunt inland," Henson reported further, "when, up to twenty years ago, their hunting was confined to the coast and the life-giving sea." These historical observations can be synthesized with traditional ecological knowledge and more modern methods of computer modeling, archaeology, and DNA.

As a Black explorer-mariner from a Jim Crow America, Matthew Henson was trying to imagine a place for himself within an American triumph story. His extensive maritime experience in the Pacific and Atlantic gave him a comparative perspective about fisheries and hunting regions around the world, while numerous polar expeditions spanning over 20 years allowed him to witness ecological and cultural transformations over time. His experience as an African American from the segregated United States perhaps allowed him to see beyond only national or colonial pride in his expeditions. As they worked more closely alongside Indigenous people who were also marginalized, mariners and fishermen of color like Henson, especially those who came in regular contact with native people and their ways of life, might have been in personal positions to more keenly empathize and to better perceive the unfolding of environmental degradation. The Inuit called Henson, in translation, "Matthew the Kind One."

Henson's memoir stresses that all people can adapt to changing environments, at a time when many American readers thought some social groups were incapable of change. He describes how the Polar Inuit had expertly adapted to their Arctic environment, and that American explorers learned from the Inuit about hunting, fishing, traveling, and dressing-essentially how to survive in the Arctic. Henson's memoir stands in partial contrast to not only the Pearys' accounts, but to John Muir's journal of his 1881 Arctic expedition, which dismisses native Aleuts as a people he assumed would be wiped out by environmental forces and racial competition, "fading away like other Indians." While Henson demeaned the Inuit way of life as primitive, he genuinely feared the effects of global over hunting on a culture he recognized as remarkably resilient.

A drawing of three Inuit hunters dragging up a walrus in the traditional way from the ice in the North Water region, created by Asiajuk sometime in the early 1900s during the decades of Henson's voyages to the area (Image courtesy of Ilulissat Museum, Anja Reimer)

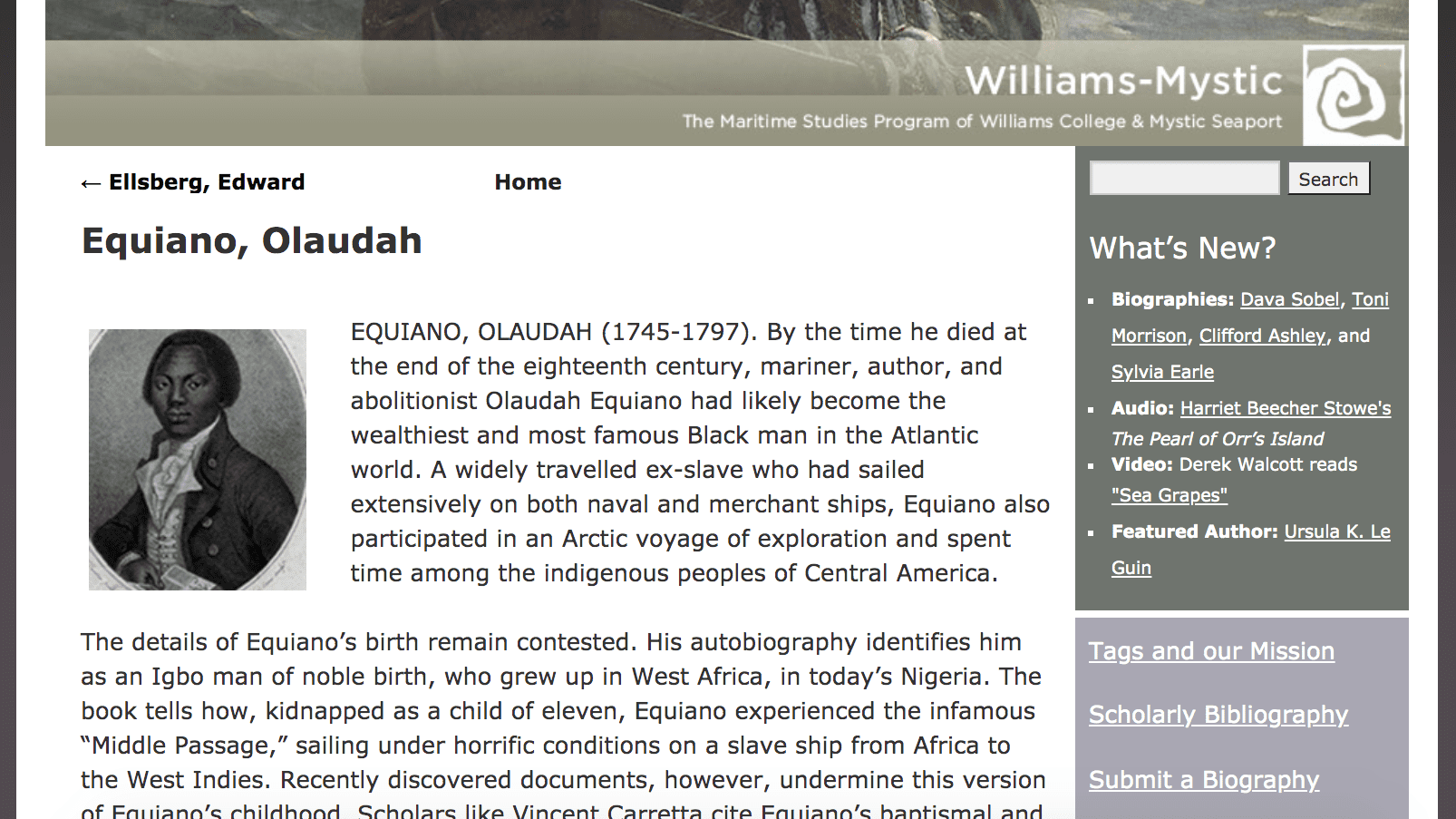

Although few historical mariners and fishermen of color were able, as Henson did, to publish their narratives in books, communicate their studies in journals, or archive their papers in museum collections, there are still documents that remain. They can be hard to find. In recent years, though, scholars have begun to retrieve and reexamine these narratives, highlight them, and provide wide electronic access to these voices. These free digital collections are now indispensable tools for environmental historians and other researchers. For example, the website database Searchable Sea Literature (one of us is an editor), offers open access peer-reviewed biographies and collects full-text electronic narratives allowing the search for race, gender, ethnicity, geography, and types of ocean experience. The website links to other databases such as Archive.org, HathiTrust, Google Books, Project Gutenberg, and the Biodiversity Heritage Library. It would be hard to overestimate how much over the last two decades these open access resources have expanded the international opportunities for research across a range of disciplines that study the ocean.

A "Searchable Sea Literature" peer-reviewed entry on the mariner Olaudah Equiano, which links to his popular narrative of 1789, another rare and crucial source for a range of ocean scholars (Image courtesy of Richard King and David Anderson)

Expanding environmental histories

Michael Moore's We Are All Whalers is only one example of recent research that embraces a range of source material. The value of seeking diverse voices and accessing digital archives is exemplified in the recent work of Sharika Crawford, a historian at the US Naval Academy and the author of The Last Turtlemen of the Caribbean (2020). Her book discusses the environmental history of the sea turtle trade that radiated out from the Cayman Islands since first European contact. This region was once abundant with green and hawksbill turtles, but the population crashed by 1800 due to overfishing and egg harvesting on the beach. So Cayman fishermen began sailing down to the Central American coast to hunt other populations of sea turtles. The serial depletion of green turtles-brought about by international demand-harmed local subsistence fishers in similar ways to how Arctic communities suffered due to colonial overhunting of walrus and bowhead.

Professor Sharika Crawford in her office at the US Naval Academy (Photo by Cathy Higgins)

Crawford's research highlights the work by conservation biologist and author Archie Carr Jr. who, beginning in the 1950s, drew from a range of available knowledge, especially from the fishermen themselves, to piece together sea turtle migration and behavior to aid the recovery of the turtle populations while trying to restore the food source for small Caribbean communities. Carr established research stations, employed local people, and took the time to learn the interests of the villagers. In a 1954 speech to the American Institute of Biological Sciences, Carr said of the fishermen's expertise: "You may call it folklore but it's the kind that has to be mostly right or somebody will starve."

In The Last Turtlemen, Crawford meshed together these accounts to compile her environmental history of the turtles, the politics of centuries of hunting, and the challenges facing current efforts to protect these migratory species across fluid international borders. She points out that in many cases, voices and records don't stem from published works. "They are often unpublished manuscripts and oral histories," she says. "More and more communities are creating memory banks and repositories. In many communities, like in the Caribbean and parts of Africa, orality is vibrant. Written sources are not the primary method for recording the past."

Michael Moore puts the challenges for Western researchers this way: "There's a paucity of written records and an inherent bias to the perspective of the commercial exploiters of such ecosystems, given that those scientists' education was crafted by societies doing the exploitation."

As with Moore's experience with Project Jukebox, Crawford explains how fortunate she was to find out about the turtlemen oral history collection, which had been started in the 1970s and had even already been transcribed for the Cayman Islands National Archives. Ideal for her environmental work, the interviewers had asked their elders, the turtlemen, about sea conditions and marine life.

"So why wouldn't we take the accounts of these captains seriously?" Crawford asks.

Matthew A. Henson, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, Co., 1912.

Sharika Crawford, The Last Turtlemen: Waterscapes of Labor, Conservation, and Boundary Making. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

Archie Carr, "The Passing of the Fleet," AIBS Bulletin 5, no. 5 (Oct. 1954), 17-19.