Freeze, peel. Peel, freeze.

At times, Matthew Henson’s frostbitten face could have been mistaken for uncooked hamburger.

Matthew Henson (1866–1955) was the first African American to reach the North Pole. (Photo courtesy of the United States Library of Congress)

“The skin keeps peeling off and freezing again until that part of the face is like raw beef and it leaves spots on the face like smallpox,” Henson wrote in “A Negro Explorer at the North Pole,” a memoir about his 22 years of polar exploration.

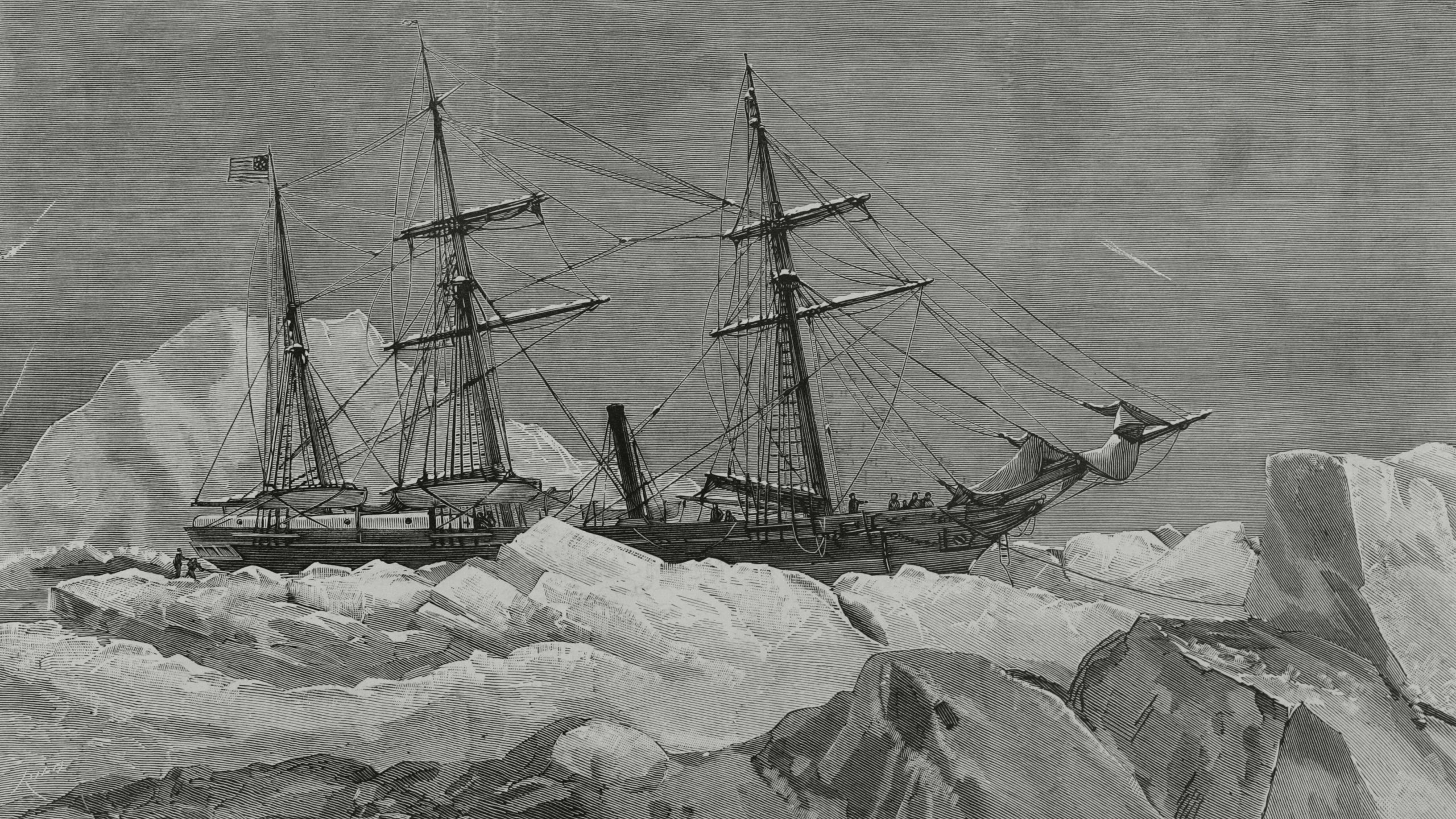

Henson’s complexion fell victim to the punishing 50-below temps, but his hands were likely okay thanks to a pair of dual-layered mittens. The outer layer, made from sealskin, kept water out while the inside layer, made from polar bear fur, blanketed his digits in warmth. The mittens were crafted for Henson by the wife of an Inuit expedition guide on the historic North Pole Discovery Expedition in 1909, when Henson became the first African-American to stand on top of the world.

Years later, Henson stored his trusty mitts at home until 1934, when he gifted them to The Explorers Club in New York City. Lacey Flint, the Club’s curator, says the mittens were matted, brittle, and eventually had to be restored.

“Our goal wasn’t to make them look brand new—we wanted to make sure to keep the wear-and-tear that was part of the artifact’s history,” Flint said. “But since they’d be on display to the public, it was important that they’d be stable and last for a long time.”

Flint sent the mittens to the Winterthur/University of Delaware (UD) Program in Art Conservation in 2017, where then-student Caitlin Richeson spent a painstaking year treating them. This involved humidifying the mittens with water vapor to relax the creases and folds, and creating inserts to give them support and shape.

“They had lost their three-dimensionality and didn’t represent the objects as they were used by Henson,” Richeson said.

The restored mittens went back to The Explorers Club in 2018, where they’re currently on display. Flint says they’re an important acknowledgement of the collaborative, yet understated efforts of Henson during that 1909 expedition.

“Henson and [Arctic explorer] Robert Peary, had made a series of unsuccessful attempts at reaching the North Pole before the 1909 expedition,” said Flint. “Eventually, it was Henson who realized the expedition team should collaborate with the Inuit and learn and adopt their methods.”

Henson’s instincts were good—they finally reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909. “A thrill of patriotism ran through me and I raised my voice to cheer the starry emblem of my native land,” he wrote in his memoir.

After returning to America, Peary was lauded as a hero for the monumental feat, while Henson garnered relatively little recognition until later in life.

“So often it’s just the expedition leader who gets the recognition,” said Flint. “But in reality, it’s never really just one person.”

Richeson agrees, and says it can be easy to lose sight of the people behind an object like a pair of mittens.

“History didn’t always remember him, but in preserving the mittens and ensuring continued access for others to see and appreciate them, it felt like I was able to honor Matthew Henson.”