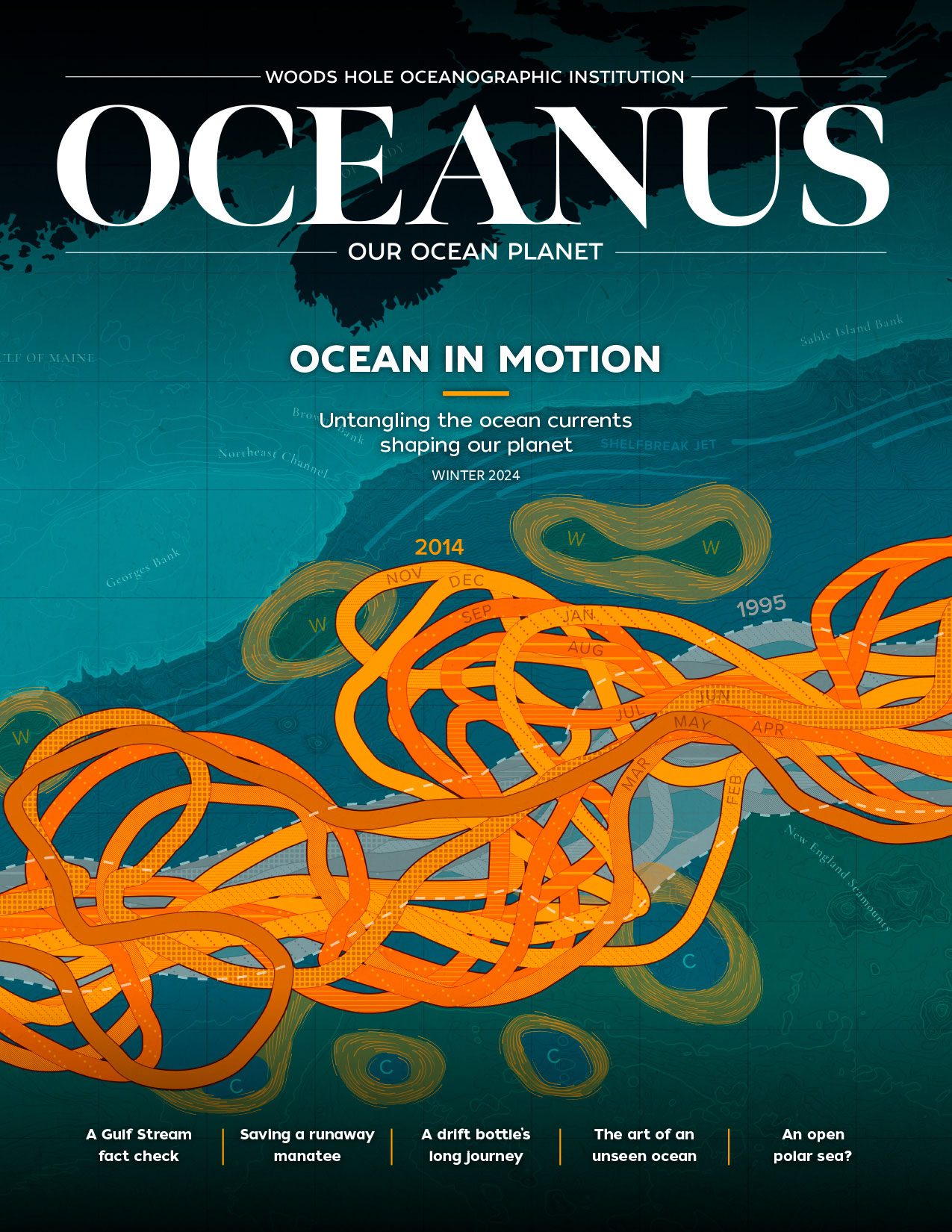

An Oceanographer’s Atlas

Ocean currents, fishing shoals, and imaginary places in one scientist’s map collection

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

Estimated reading time: 1 minute

Glen Gawarkiewicz is a thoroughly modern physical oceanographer. He studies continental shelf processes and the impact of climate change on fisheries. He uses data collected by autonomous underwater vehicles and observatories that continuously sense ocean conditions. But his career, which relies on new technologies, draws inspiration from the ancient world, maritime history, and a childhood spent abroad.

At his home, Gawarkiewicz has a collection of more than 25 original antique maps, some dating as far back as 1535. Most show areas he knows from scientific voyages but others document features that have vanished from the earth (or never existed). Many of these maps reveal how earlier generations understood the same regions Gawarkiewicz studies today.

Glen Gawarkiewicz is a thoroughly modern physical oceanographer. He studies continental shelf processes and the impact of climate change on fisheries. He uses data collected by autonomous underwater vehicles and observatories that continuously sense ocean conditions. But his career, which relies on new technologies, draws inspiration from the ancient world, maritime history, and a childhood spent abroad.

At his home, Gawarkiewicz has a collection of more than 25 original antique maps, some dating as far back as 1535. Most show areas he knows from scientific voyages but others document features that have vanished from the earth (or never existed). Many of these maps reveal how earlier generations understood the same regions Gawarkiewicz studies today.

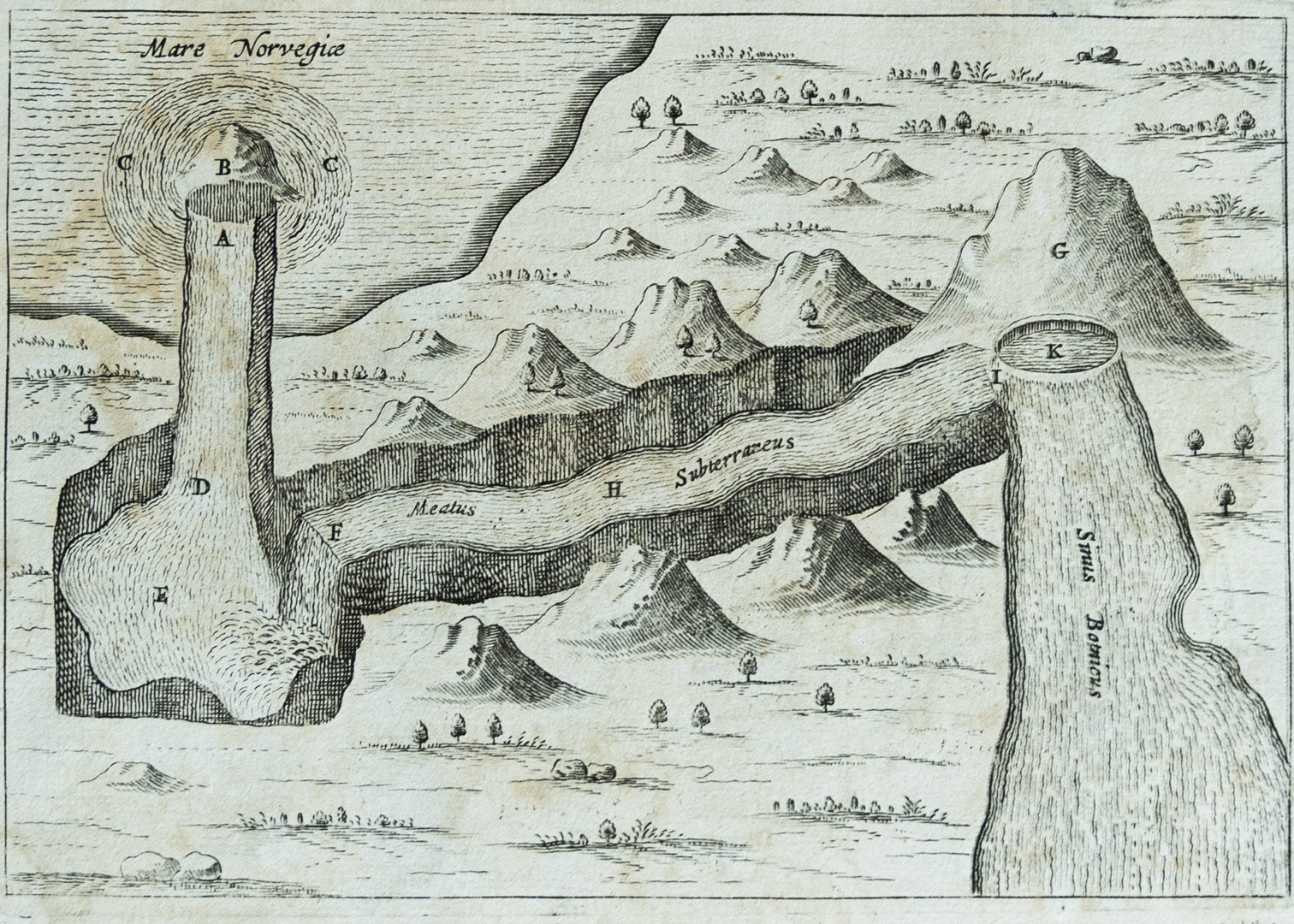

A tunnel under norway and sweden

Mundus Subterraneus, Athanasius Kircher, 1665

This page from a world atlas is the first map Gawarkiewicz ever purchased, early in his career at WHOI. He acquired this map when he was studying how North Atlantic water circulated out of the Barents Sea and back into the Norwegian Sea. One side shows currents in the Norwegian sea and the coastline of northern Europe, the other shows a tunnel that originates in the Norwegian Sea, passes under Norway and Sweden, and drains into the Gulf of Bothnia. While a tunnel connecting those seas has never been found, Kircher’s map explores the same questions Gawarkiewicz and his colleagues investigate more than three hundred years later.

This page from Mundus was the beginning of Gawarkiewicz’s map collection—and his fascination with Kircher. He has since acquired three more pages from the book: one depicts ocean currents around the Americas, including the Gulf Stream and an unrealistically large Lake Titicaca; another shows a sketch of a dragon; and a final page portrays the continent Atlantis, rumored to be copied from a map that originated in the library of Alexandria.

This page from a world atlas is the first map Gawarkiewicz ever purchased, early in his career at WHOI. He acquired this map when he was studying how North Atlantic water circulated out of the Barents Sea and back into the Norwegian Sea. One side shows currents in the Norwegian sea and the coastline of northern Europe, the other shows a tunnel that originates in the Norwegian Sea, passes under Norway and Sweden, and drains into the Gulf of Bothnia. While a tunnel connecting those seas has never been found, Kircher’s map explores the same questions Gawarkiewicz and his colleagues investigate more than three hundred years later.

This page from Mundus was the beginning of Gawarkiewicz’s map collection—and his fascination with Kircher. He has since acquired three more pages from the book: one depicts ocean currents around the Americas, including the Gulf Stream and an unrealistically large Lake Titicaca; another shows a sketch of a dragon; and a final page portrays the continent Atlantis, rumored to be copied from a map that originated in the library of Alexandria.

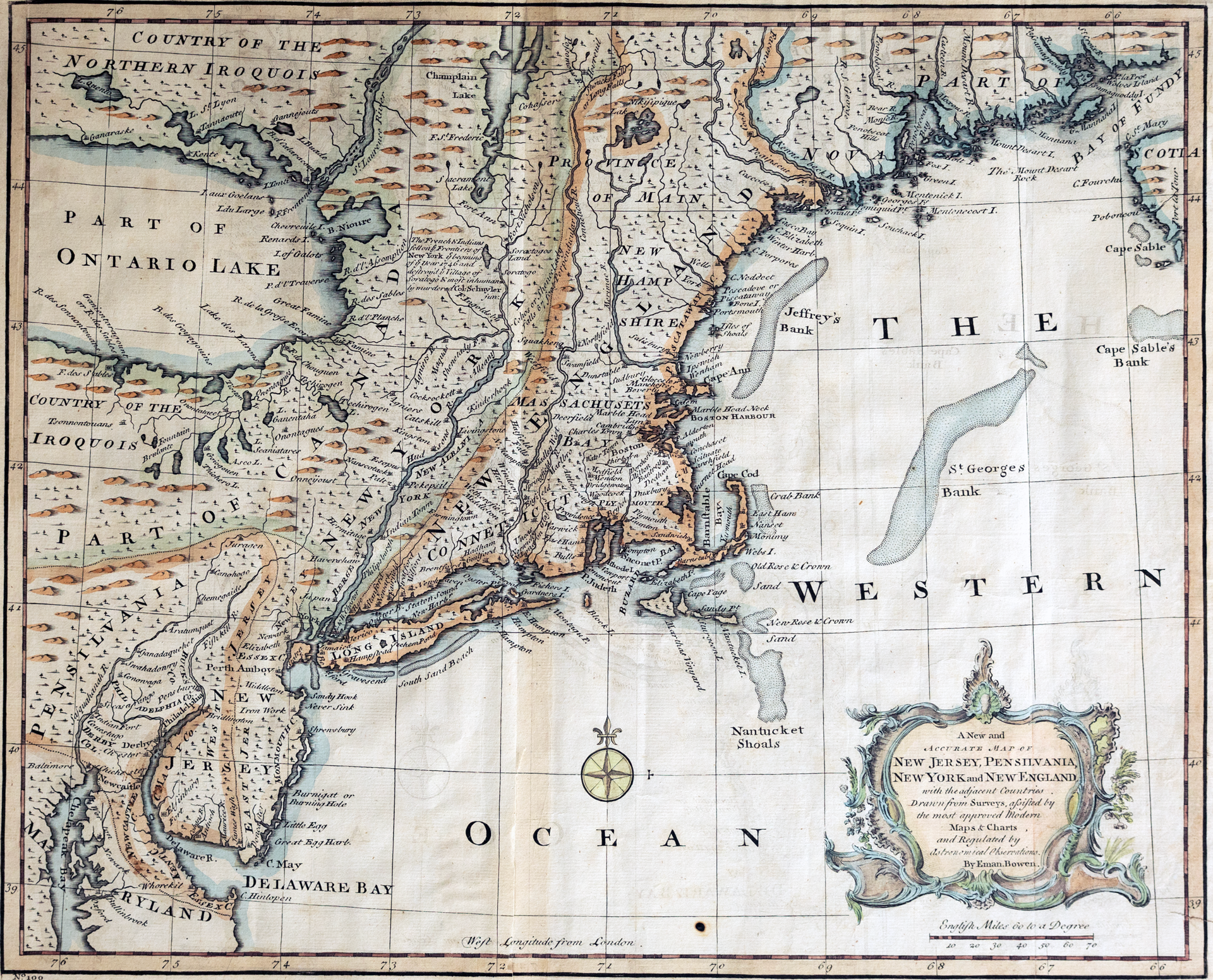

A MARINER’S GUIDE TO SHOALS

A new and accurate map of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, and New England, Emanuel Bowen, 1752

When Gawarkiewicz saw this map on display he was shocked by the accuracy of the shoals. This part of the North Atlantic is the focus of much of his research. He had just begun working with the Southern New England fishing community—equipping them with instruments that tracked ocean temperature and training them to use this data to choose fishing locations. “A map like this gives me an indication of how people thought about these areas hundreds of years ago,” he said. “Earlier generations knew our coast really well.”

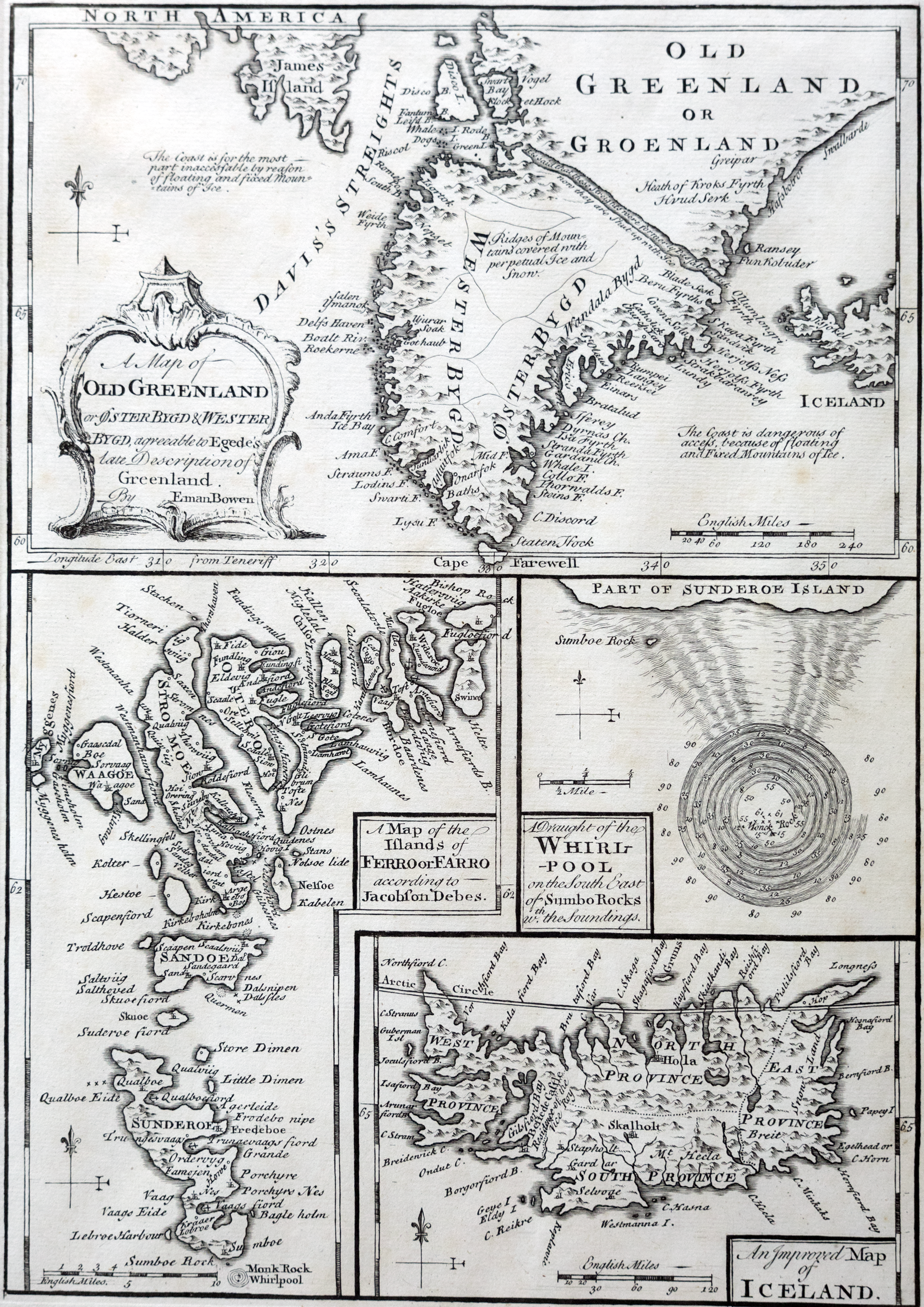

A MAELSTROM AROUND A SEAMOUNT

An improved map of Iceland, Emanuel Bowen, 1741

This map shows a whirlpool that hovered over a seamount north of the Orkney Islands and posed a dangerous threat to mariners. It also reveals a precise understanding of ocean behavior.

“This is a classic example of what we call a Taylor Column in ocean physics,” Gawarkiewicz said. “The flow of water will follow lines of constant depth, but if you’ve got a seamount, the lines of constant depth are circles, so the flow just goes round and round. That is how it can get so fast.”

Several decades after the map was published there was a submarine earthquake, the seamount collapsed, and the whirlpool vanished.

This map shows a whirlpool that hovered over a seamount north of the Orkney Islands and posed a dangerous threat to mariners. It also reveals a precise understanding of ocean behavior.

“This is a classic example of what we call a Taylor Column in ocean physics,” Gawarkiewicz said. “The flow of water will follow lines of constant depth, but if you’ve got a seamount, the lines of constant depth are circles, so the flow just goes round and round. That is how it can get so fast.”

Several decades after the map was published there was a submarine earthquake, the seamount collapsed, and the whirlpool vanished.

ANOTHER VIEW OF HOME

Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova, Willem Janszoon Blaeu, 1630

This is the most expensive map in Gawarkiewicz's collection. It shows the Chesapeake Bay, New York City, Cape Cod, and the Gulf of Maine. This map has an unusual orientation, with west at the top, and is illuminated with animals and plants found in the area.

“This is first depiction of a lot of these animals in European art,” Gawarkiewicz said. “It has beavers, turkeys, and polar bears. I just love this map.”

Owning originals by this Dutch mapmaker has personal significance to Gawarkiewicz. As a child, Gawarkiewicz’s father was in the U.S. Navy and they lived in London, Bangkok, and in several cities across the eastern United States. In each new home, his family hung a reproduction of Blaeu’s world map.

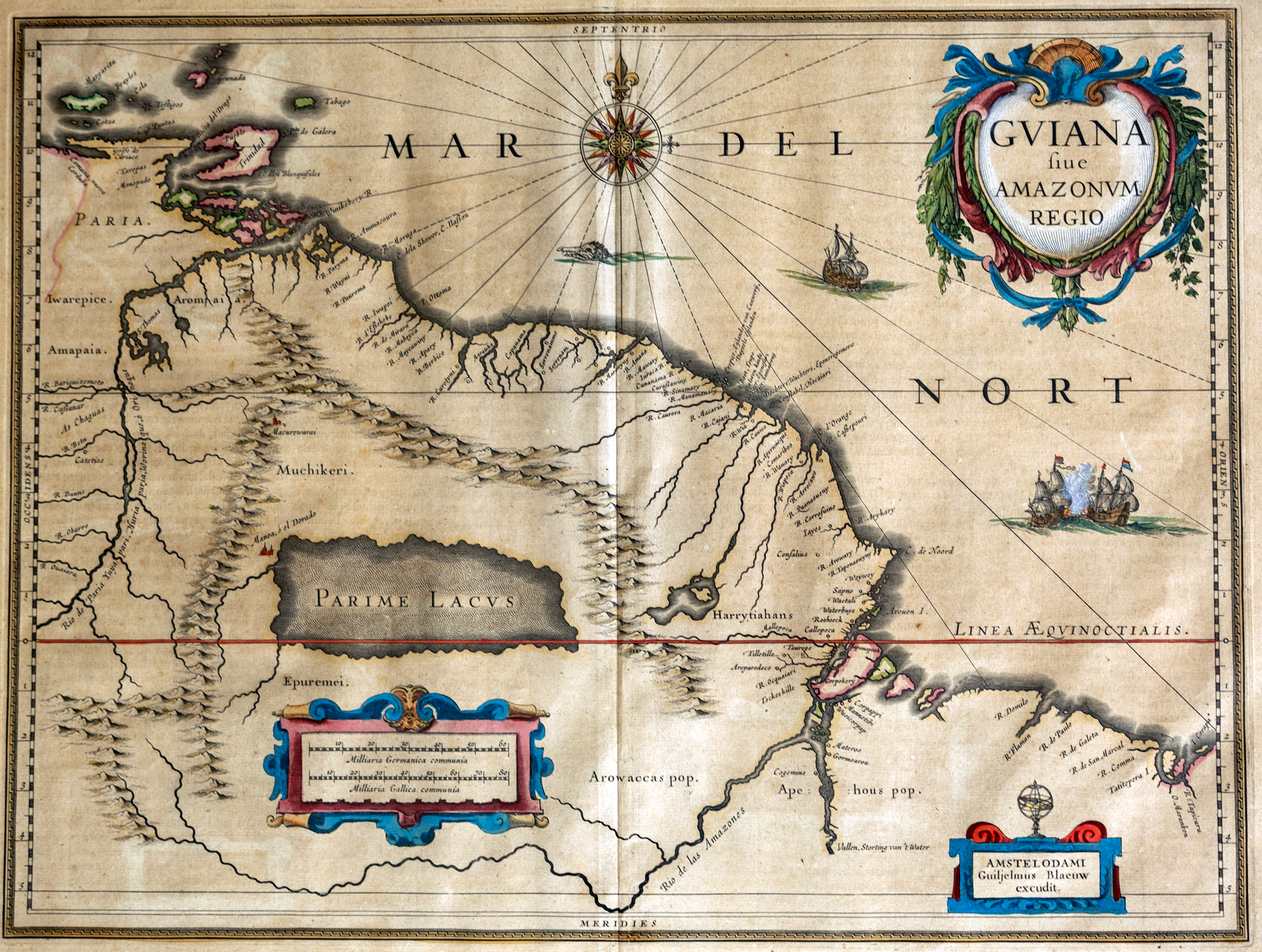

AN IMAGINARY CITY

Gviana sive Amanzonvm Regio, Willem Janszoon Blaeu, 1640

On the western bank of an inland sea is a small red city labeled El dorado, part of a larger map that shows the coastline of Venezuela. Legends of this city of gold inspired Europeans to pursue what was often a bloody quest across South America. This map was made to trace the travels of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595, forty-five years after the fact.

“This is really my counterpart map to the one I have of the lost continent of Atlantis,” Gawarkiewicz said, "I normally get maps of the places that I've been to on cruises and travels. But there are some places you can’t go.”