Current Events off Antarctica

Graduate student helps discover a previously unknown ocean current

The scientific method can divert researchers down curious pathways. Human psychologists study mouse brains. Astrophysicists look for cosmic particles deep in mine shafts. Taxonomists trace bird evolution by studying feather lice.

Carlos Moffat’s scientific career took a similar detour. Fascinated by marine biology, he became a physical oceanographer to understand the ways ocean water moves, mixes, and nourishes life at the bottom of the marine food chain.

“I am one of those kids that spent a lot of time looking at ants and stuff,” Moffat said. But after studying biology at the University of Concepción, Chile, “I remember having the MIT/WHOI Joint Program application in front of me and I had to decide between biological or physical oceanography. I realized to be a good biological oceanographer requires understanding physics.”

Not long afterward, Moffat helped discover an ocean current that even in the 21st century had remained unknown to humankind. It’s understandable why it took so long. The newfound current flows south along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, a 745-mile (1,200-kilometer) spit of ice and mountains that stretches north toward the Drake Passage and Tierra del Fuego.

About halfway along the peninsula, the current dips into Marguerite Bay, a vibrant nursery for the shrimplike krill that feed most of the Antarctic’s animal life. Some scientists speculate that the newly named Antarctic Peninsula Coastal Current may help sustain the biological smorgasbord of krill, Antarctic cod, penguins, leopard seals, and whales in the Southern Ocean that surrounds the icy continent.

Something new under the water

Hints of the Antarctic Peninsula Coastal Current first showed up on measurements taken by Robert Beardsley, an emeritus scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and Moffat’s co-advisor (with WHOI physical oceanographer Breck Owens). Near Marguerite Bay, Beardsley noticed a patch of unusually fresh water about 10.8 nautical miles (20 kilometers) offshore, floating atop saltier, denser water.

In a stroke of serendipity, a biological survey led by WHOI biologist Peter Wiebe had cut straight across the patch, Moffat learned. The survey used BIOMAPER-II, an instrument that uses sonar to look for marine animals while recording temperature, salinity, and other basic data about the water. BIOMAPER measures continuously as a ship drags it through the water—a vast improvement over previous physical oceanography surveys in the area, which took measurements only every 10.8 nautical miles (20 kilometers).

After some analysis with fellow graduate student (and BIOMAPER expert) Gareth Lawson, Moffat found that the fresher water hit a wall of saltier water offshore and deflected southward along the coast. Next, Moffat calculated the current’s vital statistics using data from a current sensor, deployed by Beardsley in 2001-2002, that had somehow survived an entire winter in an ice-choked sea.

‘On’ in summer, ‘off’ in winter

Moffat found that the current rumbles southward at about 14 inches (35 centimeters) per second (or not quite as fast as windshield wipers move on the “slow” setting). The strongest part of the current is 5.4 natuical miles (10 kilometers) wide and about 656 feet (200 meters) deep. In all, Moffat estimated, the current conveys about 0.32 Sverdrups of water each year (a Sverdrup is 1 million cubic meters or 264 million U.S. gallons per second). This is a trickle by ocean standards, but nearly twice the volume of the Amazon River. Most of that surge comes during the summer; Moffat found that the current shuts down each winter when the coastal waters freeze over.

The fresh water contained in the current’s yearly flow totals about 30 cubic miles (126 cubic kilometers)—enough to submerge all of Cape Cod under 394 feet or 120 meters of water). Working with colleagues at the British Antarctic Survey and the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium, Moffat calculated that most of that fresh water arrives as meltwater from the peninsula’s 1.75-mile (2,800-meter) -high mountains, kicking the coastal current back into action as summer begins. As the water runs off the land, it may bring nutrients that help recharge the growth of marine plants and animals in the coastal waters, Moffat said.

In the larger picture, as Wiebe has suggested, the waters of the new current may interject nutrients or juvenile krill from Marguerite Bay into the much larger Antarctic Coastal Current, to feed waters teeming with life as far away as South Georgia Island and the Weddell Sea. (See “Voyages into the Antarctic Winter.”)

Science and cinema

Moffat, 30, grew up in and around Concepción, Chile, but traces his roots to Scotland, which has both a town called Moffat and a gray-black-and-red Moffat tartan. He met several WHOI scientists in 2001 when they attended the inaugural Austral Summer Institute in Concepción, a monthlong oceanographic symposium now in its seventh year.

The institute’s organizers had hired a promising undergraduate assistant, remembers John Farrington, former dean of the MIT/WHOI Joint Program. “And that was Carlos Moffat. We were all really impressed with him. He was a biologist, but he had a strong mathematics background and had already read some papers by Henry Stommel,” a WHOI physical oceanographer who was a giant in the field.

“I encouraged him to apply for the Joint Program,” Farrington said, and when Moffat came to WHOI later that year, as a Chilean Presidential Fellow, Farrington welcomed him with a copy of Stommel’s collected reprints.

By all accounts, Moffat’s English was exemplary from the start, but he says he learned to speak less formally after watching American movies. His interest in U.S. cinema, which began back in Chile, eventually put him in charge of a weekly graduate student movie night known for eclectic choices including How to Marry a Millionaire, Wicker Man (the 1973 cult hit, not the 2006 flop), and Machuca, a 2004 film about Chile in the turbulent 1970s.

Applying Seinfeld to climate change

Moffat reads voraciously. Back issues of Linux Journal litter his living room and an empty Amazon.com box sits on his office desk, perfect for putting his laptop screen at eye level. Despite a demanding schedule—he defends his Ph.D. in 2007—he keeps a lively blog in Spanish that rarely mentions oceanography. A recent post suggested it was about time Disney let el ratón Mickey pass into the public domain.

Just as Moffat turned to physical oceanography to help him understand biology, he looks for science to bring solutions to the real world. After studying the Antarctic Peninsula, one of the fastest-warming places on the planet, he wishes more people took climate change seriously.

For him, pop culture already has the right approach, at least when viewed with his own wry wit. “Like when we got the news that Greenland is melting: All these oil companies were getting really excited, because now they can go there and look for oil,” he said. “It’s like when Seinfeld went skydiving. Any time you get to the point where you are buying a helmet, you should stop and think about what you are doing. When it comes to climate change, it’s the same thing.”

Funding for this research came from the Chilean Presidential Fellowship Program, the Coastal Ocean Institute at WHOI, the Cooperative Institute for Climate and Ocean Research at WHOI, and the National Science Foundation.

From the Series

Slideshow

Slideshow

- The newly discovered Antarctic Peninsula Coastal (APCC) Current hugs the west coast of the 745-mile-long peninsula. The current is reinvigorated as summer begins by fresh meltwater from the peninsula?s mountains, which also washes nutrients from land into the ocean. APCC waters may inject nutrients and juvenile krill from Marguerite Bay into the much larger Antarctic Coastal Current (ACC)to foster marine ecosystem farther away. Red, black, and red/black dots represent sites where moorings were deployed in various years to help measure currents. Solid blue arrows respresent areas where the new APCC was observed directly; dotted blue arrows represent the current's possible, still-unobserved pathways. (Carlos Moffat, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

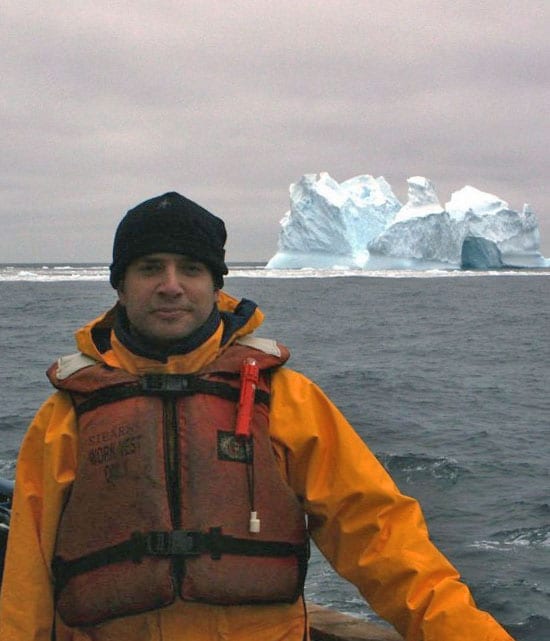

- MIT/WHOI Joint Program graduate student Carlos Moffat used an instrument called a CTD rosette to measure temperature, salinity, and other water characteristics on a 2005 research cruise aboard R/V Revelle that started in Tahiti (16?S). (Courtesy of Carlos Moffat, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- By the time the six-week cruise ended in the Southern Ocean (71?S), Moffat had put away his shorts and was seeing icebergs. (Courtesy of Carlos Moffat, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Voyages into the Antarctic Winter An article on Antarctic krill research and hints of the new current. from Oceanus magazine