An open polar sea?

The once-romanticized notion of an ice-free Arctic comes full circle

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2024

Estimated reading time: 3 minutes

According to recent climate research from the University of Colorado Boulder, sea ice in the Arctic is shrinking faster than previously thought. In fact, at the current rate, the Arctic could experience its first ice-free days at some point this decade, according to the study.

Welp.

The idea of an ice-free Arctic, however, is nothing new. Just a little over a century ago, Victorian-era polar explorers rather fancied the concept of an “open polar sea”—a North Pole surrounded by nothing but seawater. With an open body of water and little or no sea ice to navigate through, expedition teams could take advantage of the presumed shortcut passage between Europe and the Pacific, shaving thousands of kilometers off the typical route to Northern Asia.

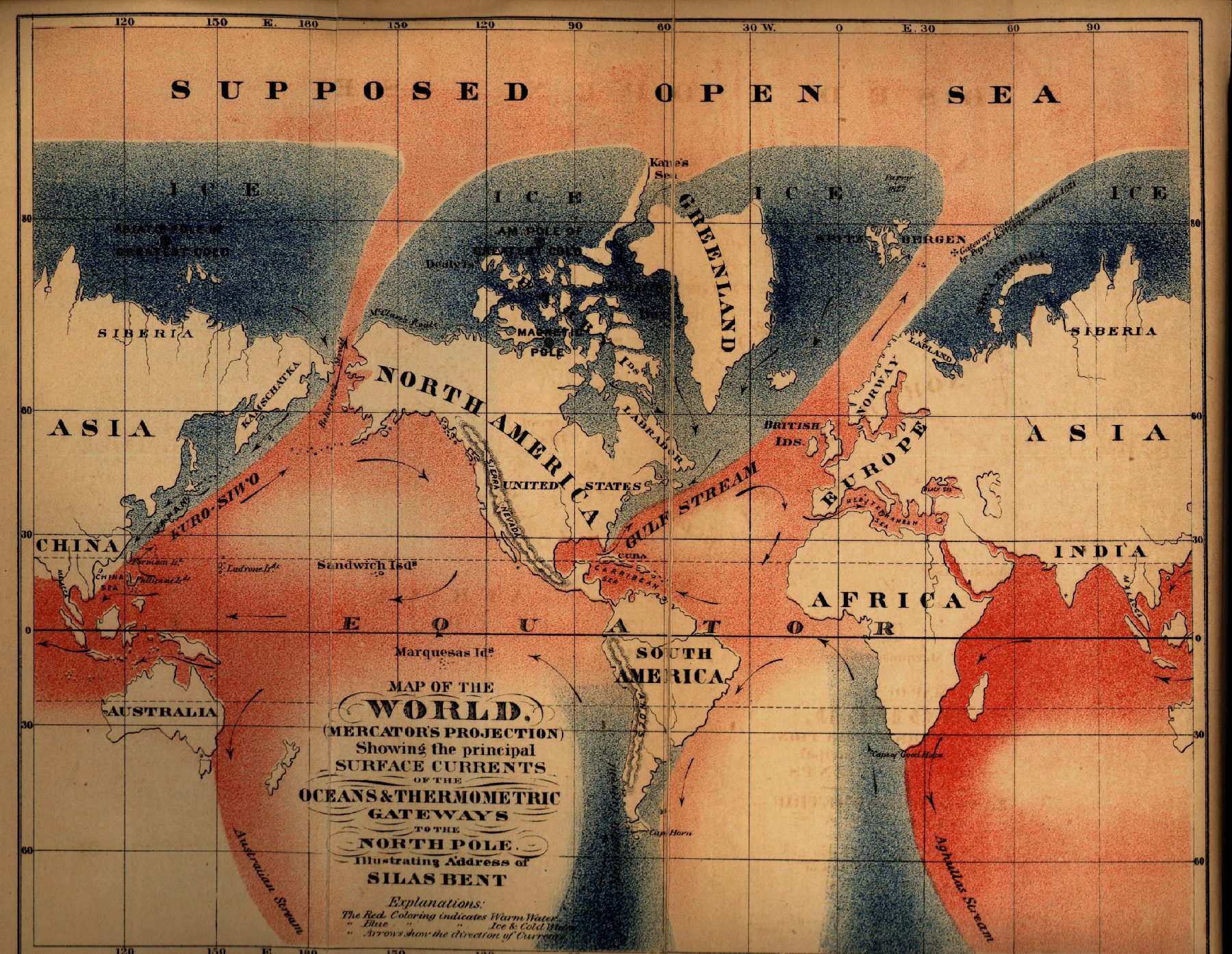

The wishful thinking was fueled, in part, by the idea that as warm ocean currents from the Gulf Stream traveled north, they’d prevent ice from forming around the pole.

An article entitled, “Cause of the open polar sea” published in the December 29, 1855 edition of Scientific American, suggested that, “the water of the ocean at the equator and within the tropics is not only heated at its surface by the surrounding atmosphere, but is also heated at its bottom. This heat is derived from the earth, its temperature being elevated by the sun's rays passing through the water, and the water heated at the bottom to about 40 degrees rises to the surface, when it attains the temperature of 87 degrees.”

When these undercurrents eventually reach the poles, the article suggested, they would accumulate “in an immense body, at a temperature of 40 degrees.” This, in turn, would maintain an ice-free zone around the North Pole.

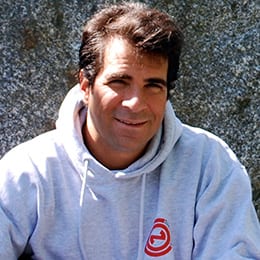

Scientists at the time already knew that the Gulf Stream kept Europe warmer, and that its warm waters flowed into the Arctic and cold waters flowed back out. But Alan Condron, an associate scientist at WHOI who studies the Arctic, said that the scientific community’s understanding of Arctic oceanography was generally poor back then.

“Scientists almost had it right,” said Condron about their hunch of an open polar sea. “But they overestimated how much heat was going in and didn’t account for things like heat loss to the atmosphere.”

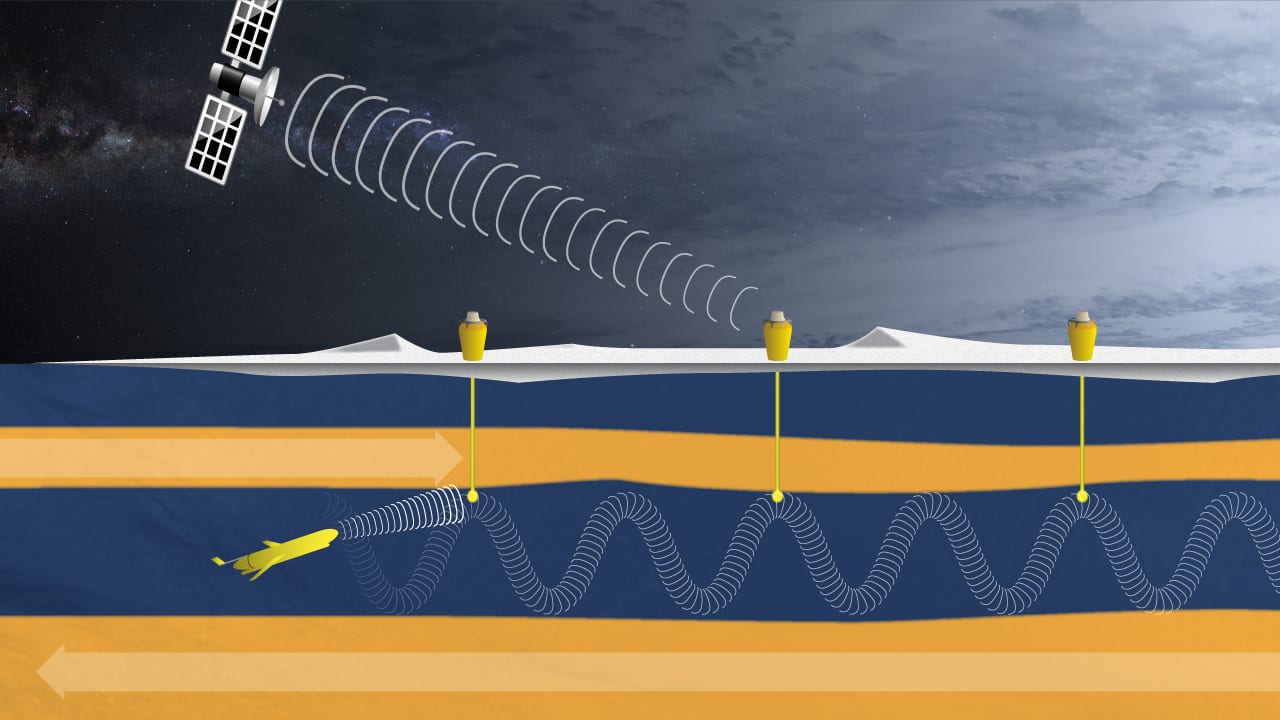

Another factor, Condron explained, is that researchers weren’t clued in about the horizontally layered or “stratified” structure of the ocean’s water column. When sea ice forms, it releases salt into surface waters, which become dense and sink. These denser waters ultimately form a barrier of cold water—known as the Arctic halocline—which prevents the underlying warm Gulf Stream water from melting the sea ice above.

The northward flow of warm waters was just one explanation for the open polar sea theory. Some people thought seawater was too salty to freeze; others assumed the Arctic’s 24-hour summer daylight would have melted everything. There were also those who believed that sea ice only formed right along the coast and wouldn’t jam up the open ocean.

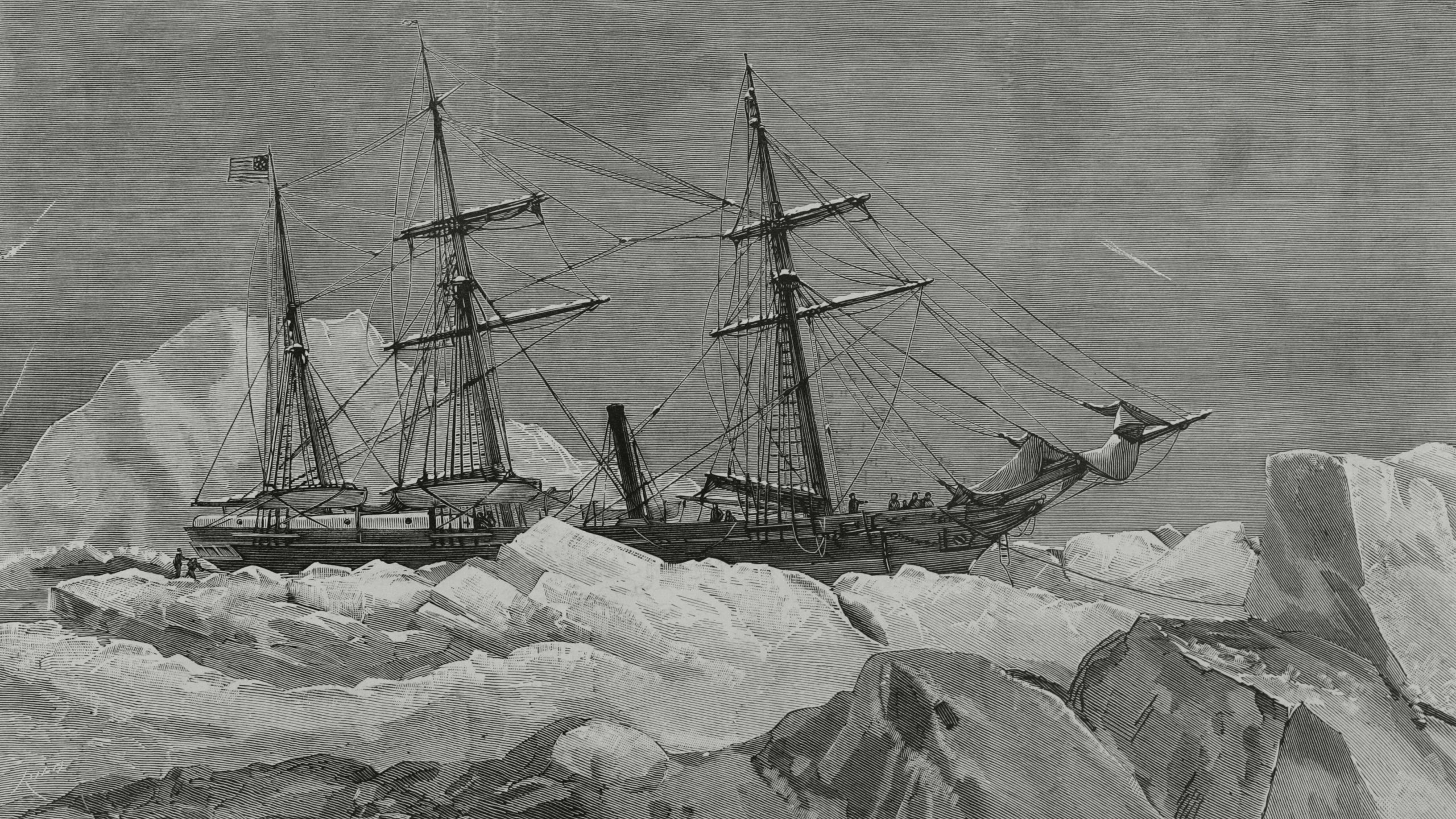

As imaginations ran wild, explorers hoping to find an open path to the Pacific were met with a sea forged in ice upon arrival. During one expedition, Arctic explorer George W. De Long and his crew set sail to the North Pole on the USS Jeannette, a three-masted former British navy gun vessel that had been adapted for polar exploration. The ship eventually became trapped in ice and drifted for two years before being crushed by pack ice off the Siberian coast. When the few remaining survivors returned home and shared their accounts, the word got out: the open polar sea theory was a farce.

But today, as Arctic sea ice continues to shrink at an accelerated pace, it no longer seems like fake news. And if projections for ice-free summer days are accurate, new, faster shipping routes between the U.S., Europe, and Asia could open up and reduce transit time by anywhere from 14 to 20 days, according to estimates.

Maybe the explorers of the Victorian era were onto something after all. But given the climate crisis we’re now battling, their legacy thinking serves as a stark reminder: be careful what you wish for.