This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2023

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2023

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

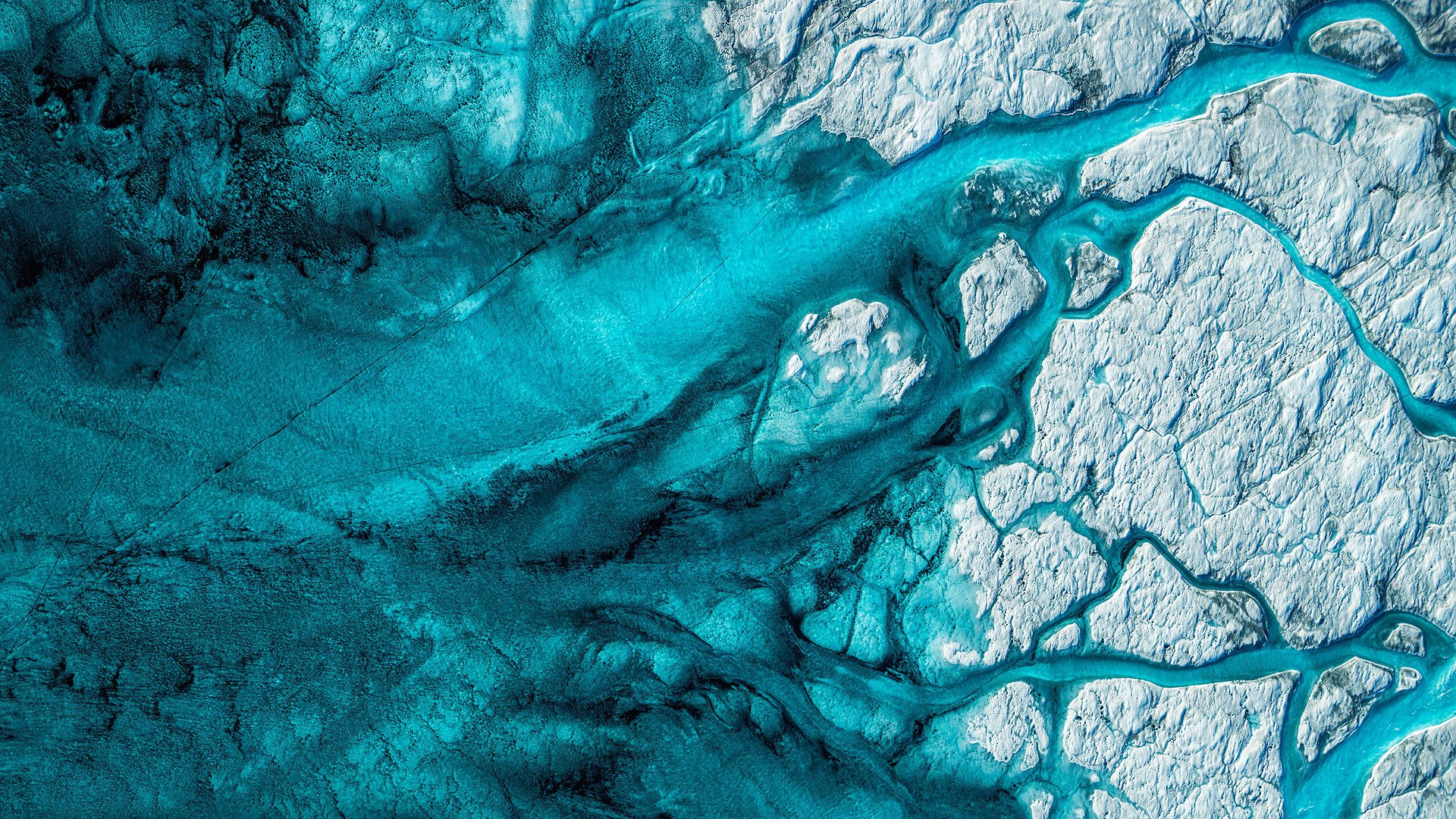

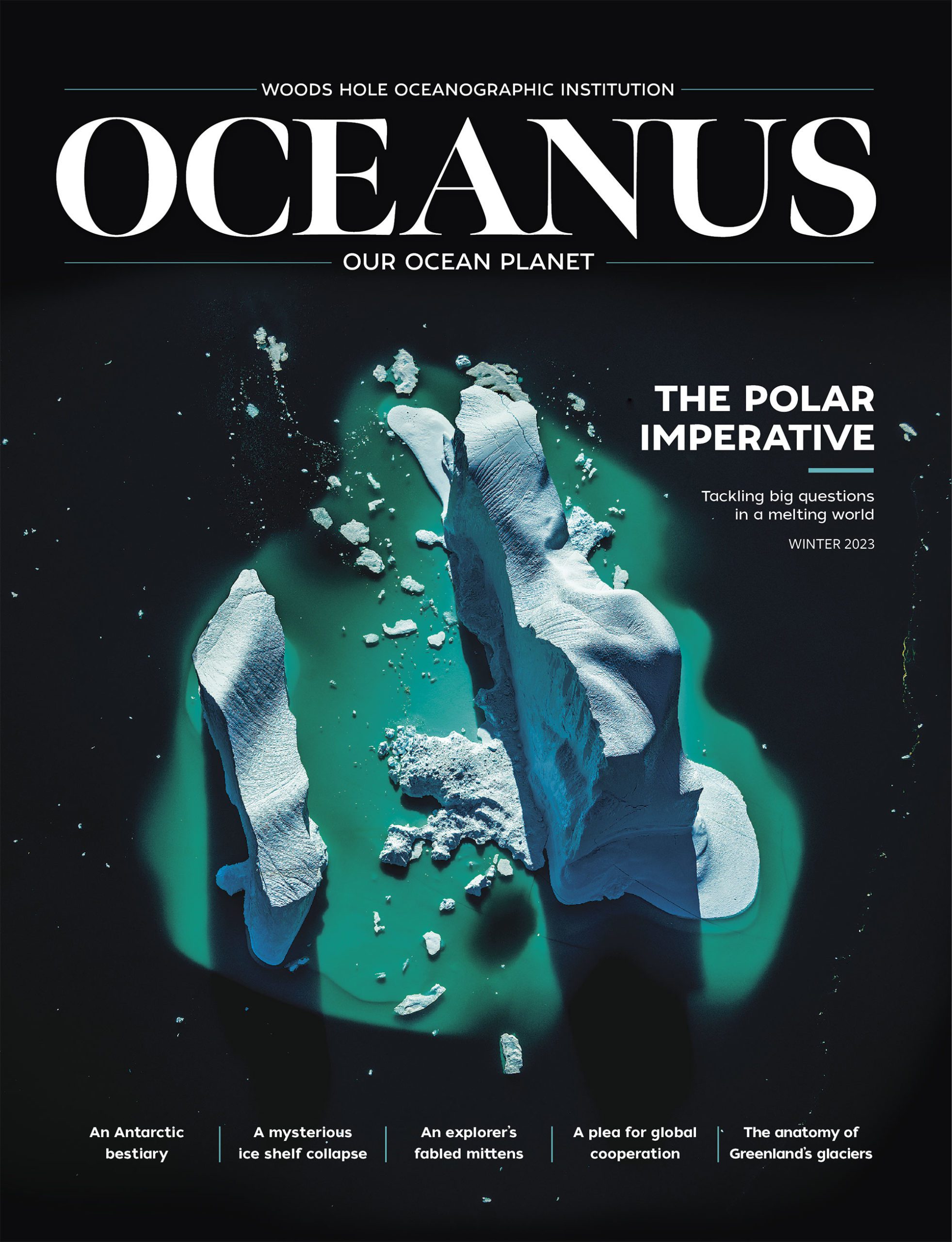

Roger Fishman knows Greenland’s secret. Though all the world’s maps might have you believe the country is a blank canvas of white, his experience flying over its glaciers has taught him otherwise. Across the 1,800 square miles that comprise Greenland’s ice sheet is a tapestry rich in turquoises, blues, greens, and blacks. Here, glacial rivers spiderweb across the country’s frozen interior, pooling and plunging into deep crevasses and craters. Fishman has seen it all. After five years of helicopter expeditions (and counting), he’s amassed a portfolio that puts the country’s ethereal and dynamic body on full display.

In this photo essay, we invite you to revisit Greenland through his eyes. You’ll see the country as it’s meant to be: an ever-changing landscape, formed and reformed by the science of ice and climate.

Though they are a composite of ice and snow, glaciers can move like rivers when observed on larger timescales. As they move, their immense weight can leave scars that shape the landscape, forming basins. The motion can also grind rocks down into a fine silt, sometimes called “rock flour.” This gives glacial lakes their iridescent, turquoise hue. In North Greenland, where this image was taken, there is only one remaining glacier (top left) feeding this glacial lagoon.

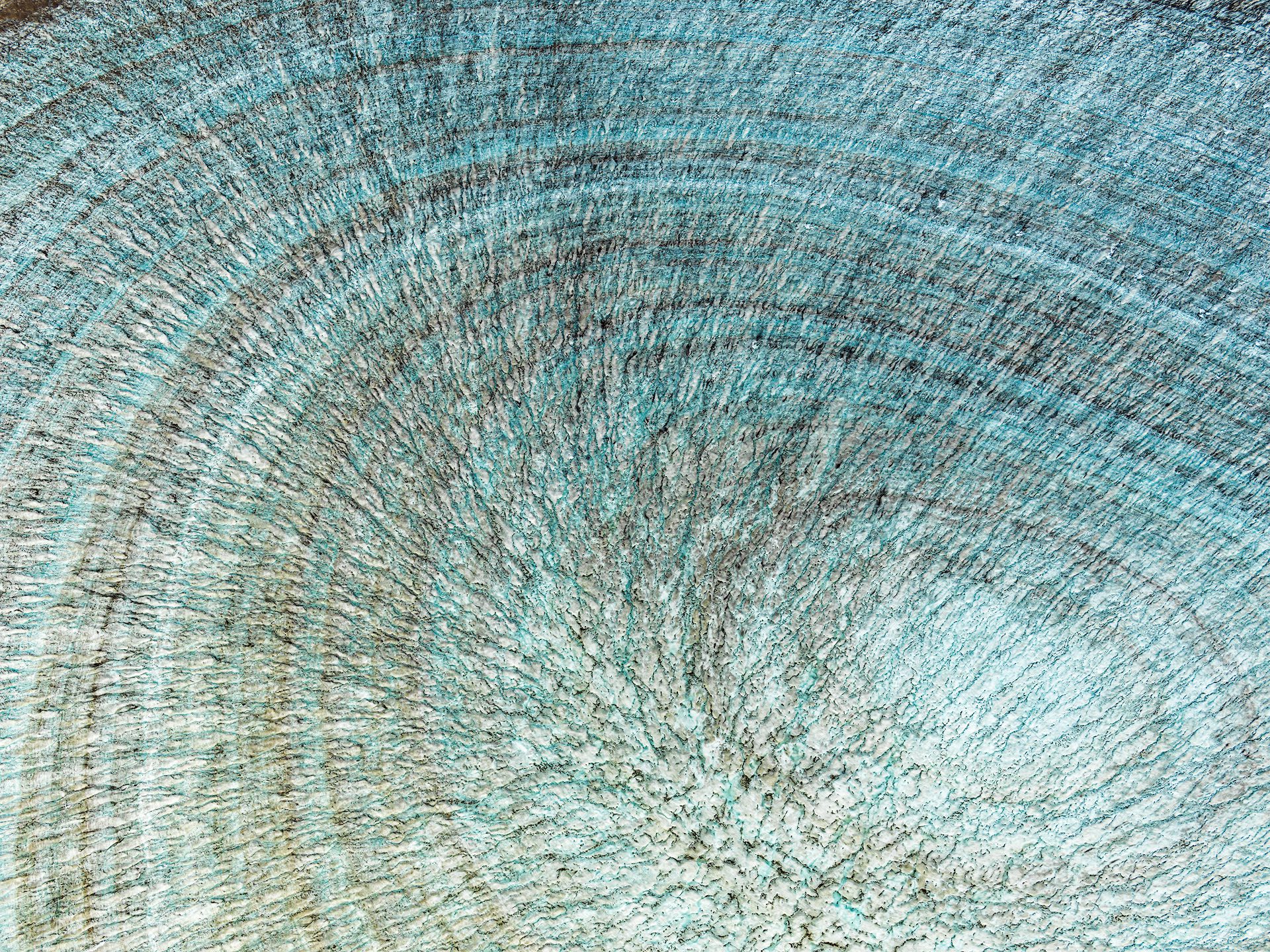

Like the rings on a tree, ice can be a superb natural archive. These concentric circles indicate thousands of years of seasonal snow that have compacted into distinct layers of ice. Air bubbles trapped inside each layer serve as small snapshots of the Earth’s atmospheric composition throughout time. By taking ice cores at various depths, scientists can analyze the chemistry of these bubbles to track Earth’s changing climate.

Black cryoconite (center of image) is a dusty material that naturally accumulates at the poles from crushed rock particles and the activity of microbes. Unlike white, reflective ice or snow, which repels sunlight from the Earth, cryoconite absorbs and traps these rays, causing ice to melt. Soot from forest fires and the burning of fossil fuels is increasing the amount of cryoconite seen on Greenland’s surface.

This glacier, photographed near Qaanaaq, Greenland, is one of many that are receding in the region as a result of warming global temperatures. At its terminus (in the foreground) is a relatively small iceberg that seems to quietly punctuate this solemn retreat. For some, this image may serve as a bleak reminder of the threats facing this natural polar beauty. For others, however, it could represent hope—an enduring optimism that the poles will hold on long enough for humanity to slow or reverse the effects of our changing climate.

See more of Fishman's work by going to his Instagram @RogerFishman