Coral Catastrophe on the Corner Rise Seamounts

Fishing trawlers likely caused extensive damage to deep-sea coral communities

A research team has found that deep-sea coral communities that provide lush habitats for fish and other marine life were extensively damaged, mostly likely by deep-sea fishing trawlers, atop two undersea mountains in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

A decade after the fishing stopped, the once abundant summits have been “effectively denuded” of bottom-dwelling animals and “no longer support habitat-forming corals in any significant numbers,” scientists reported in the October issue of the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom.

The finding spotlights a rising concern: As fishing grounds closer to shore become overfished and increasingly regulated, deep-sea habitats in unregulated waters become more attractive targets for fishing fleets.

“Though a moratorium on deep-water trawling was proposed to the United Nations General Assembly in November 2006, no consensus was reached,” the scientists wrote. “The absence of strong international action on this issue therefore leaves coral communities vulnerable to anthropogenic damage.”

Will coral communities recover?

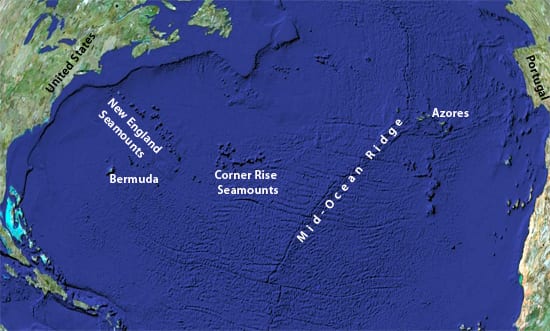

The research team—Rhian Waller, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Les Watling from the University of Maine and the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Peter Auster from the University of Connecticut, and Timothy Shank of WHOI—set out in 2005 to explore coral communities on the Corner Rise seamounts, a cluster of about 20 ancient flat-topped volcanoes at least a half-mile below the sea surface and 1,240 miles away from shore in the northwest Atlantic. It took nearly five days to get there by ship.

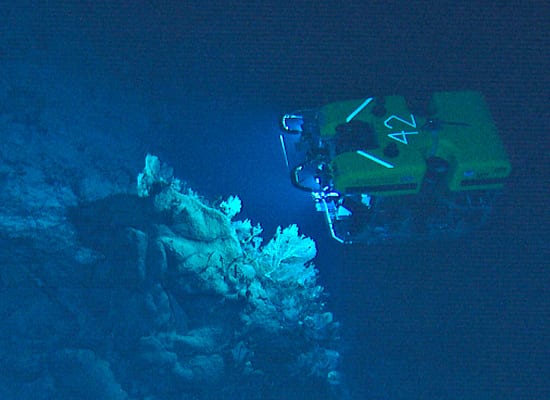

They expected to explore coralline Camelots—“pristine coral ecosystems,” they said—but the mission quickly morphed into a coral forensics investigation. A remotely operated deep-sea vehicle dispatched to “fly” up the slope of one seamount showed video images of chewed-up branches of pink bubble gum corals, which usually grow large and abundantly atop seamounts.

“The theory is that the trawls came over top of the seamount, caught the corals in the nets, and pieces that broke off slid down the sides of the seamount,” Waller said.

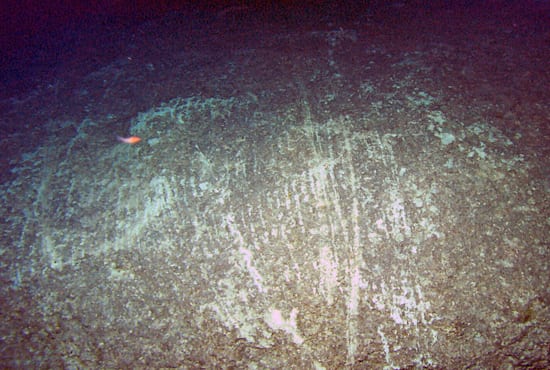

Some trawl nets, which can weigh more than two tons, are big enough to carry six jumbo Boeing 747 airliners. The nets are weighted with metal balls or rollers to ensure they rake up everything in their path. In addition to coral corpses, the team documented an assortment of gouges and trawl scars leading in all directions, scattered coral fragments and metallic waste.

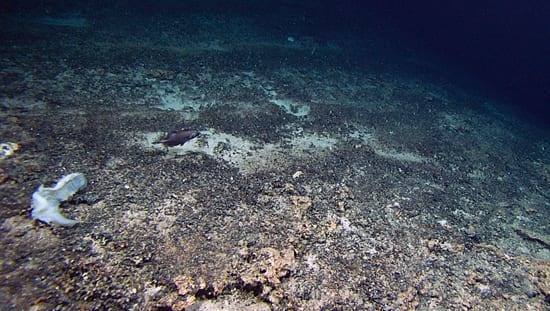

The entire top of one seamount, Kükenthal Peak, is denuded, Waller said, and on another, Yakutat Seamount, “the number of live corals documented on the plateau was negligible,” the scientists wrote.

Fishing ships from the former Soviet Union used trawls to fish the Corner Rise seamounts between 1976 and 1996, seeking the bug-eyed alfonsino fish—often sold in stores as snapper. They stopped fishing there because their catches were deemed no longer worth the expense to get to this remote area, Waller said.

“You can clearly see that these seamounts have not recovered from the trawling,” she said. “There’s a chance that abundant communities may never come back.”

Enforcing fish regulations on the high seas

Nutrient-rich currents often sweep around seamounts, seeding them with coral larvae that grow large and develop into rich deep-sea communities. About 30,000 seamounts dot the oceans worldwide, like underwater oases.

Unlike shallow-water tropical corals, deep-sea corals also live in high and mid-latitudes, at depths where the sun doesn’t penetrate. Instead of photosynthetic algae, deep-sea corals feed on small marine plankton. Deep-sea corals grow very slowly—maybe an eighth of an inch per year—and some can live for thousands of years, Waller said.

Because they can exist in remote ocean locations, scientists have only recently begun to explore deep-sea coral communities and investigate, with their ecological importance only really being investigated since the 1990s. Around the same time, bottom trawling began to be widely recognized as a particularly destructive fishing practice. Some countries have banned it outright within their exclusive economic zones, but seamounts in international waters come under the jurisdiction of regional management organizations involving several nations, and so are hard to regulate and even harder to enforce.

The Corner Rise seamounts, for example, are governed by the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization, or NAFO. In 2006 the United Nations called on the nations involved in NAFO—the European Union, Canada, the United States, Norway, Iceland, Russia, Korea, and Japan—and other fisheries management councils around the world to implement a worldwide moratorium on bottom trawling. However, NAFO failed to agree to comprehensive protection measures at their annual meeting at the end of September this year, according to a recent press release by the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

“If we stop the trawling now, are seamounts [like Corner Rise] ever going to recover?” Waller said. “We don’t know that answer.”

The team’s work on the Corner Rise seamounts was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration program.

Slideshow

Slideshow

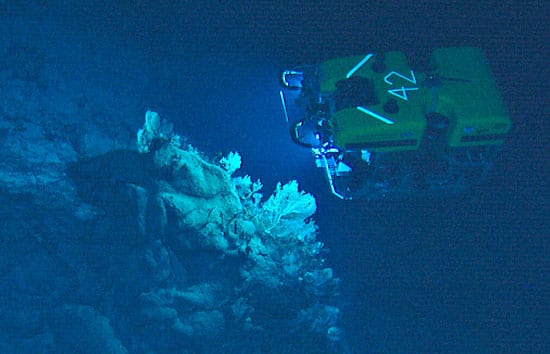

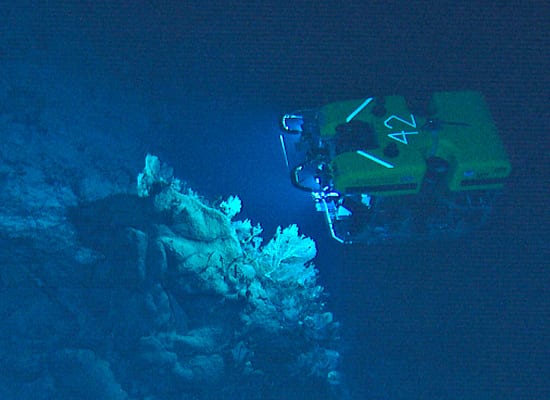

The remotely operated vehicle Hercules (URI, IFE) collects corals from the Corner Rise seamounts and takes pictures of them during a 2005 expedition. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

The remotely operated vehicle Hercules (URI, IFE) collects corals from the Corner Rise seamounts and takes pictures of them during a 2005 expedition. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)- The Corner Rise seamounts are a chain of extinct undersea volcanoes 1,240 miles from land (roughly the distance from Cape Cod to DisneyWorld).

- A bathymetry map of the Corner Rise seamount complex in the northwest Atlantic Ocean includes Yakutat Seamount and Kukenthal Peak, where scientists found extensive damage to coral habitats. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- WHOI biologist Rhian Waller holds a Desmophyllum dianthus?a solitary coral collected by the remotely operated vehicle Hercules (background) from the Corner Rise seamounts in August 2005. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- Scientists used the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown to investigate the Corner Rise seamounts in 2005. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

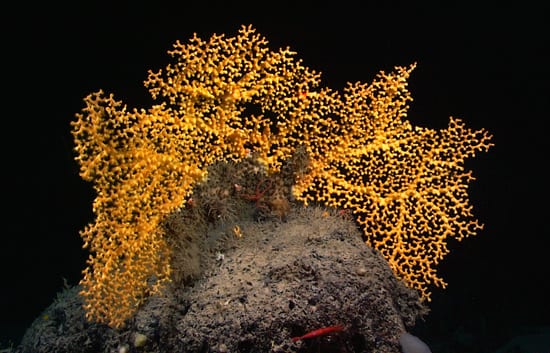

- Deep-sea corals provide habitats for lush communities of animals. Here, more than five species of coral blanket this boulder on the Yakutat Seamount, as well as many other species including brittle stars, starfish, crabs and molluscs. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- On an expedition in 2005, scientists found that much of the Yakutat Seamount had been extensively damaged by fish trawling. A large dead coral bank at the top of the Yakutat Seamount shows linear scars from trawling. An oreo fish swims by on the left. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- Scar marks caused by trawling gear bear evidence of the cause of the destruction to once abundant deep-sea coral communities on the edge of a summit plateau on the Kukenthal Peak. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

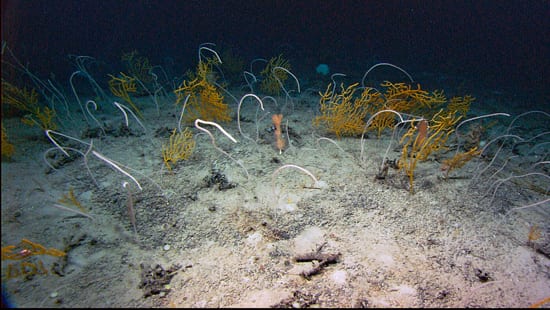

- This community of whip corals, sea fans, and bamboo corals on a plateau on the Kukenthal Peak represents one that avoided fish trawling damage that scientists say "effectively denuded" the seamount. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- This bright yellow colony of the deep-water hard coral Enallopsammia rostrata is an isolated survivor of the damage on Yakutat Seamount. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- A Mediterranean roughy hides behind an "amphitheater" sponge. The red lasers measure about 10 centimeters. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

- Deep-sea corals, such as this soft coral (Candidella species), provide habitats for fish and other deep-sea creatures such as this brittle star, with its legs held out into the current to capture food. (DASS05_URI_IFE_IAO_NOAA)

Video

Related Articles

- Our eyes on the seafloor

- Unlocking the Earth’s time capsule

- 3 memorable Jason Dives

- How did the ocean remain so quiet during Tonga’s eruption?

- With deep-sea mining, do microbes stand a chance?

- Coming full circle

- 7 Places and Things Alvin Can Explore Now

- The story of “Little Alvin” and the lost H-bomb

- Life at Rock Bottom

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Coral Gardens in Dark Depths from Oceanus magazine

- Marine Conservation Biology Institute

- Oceana Protecting the World's Oceans

- Deep Sea Conservation Coalition

- Lullabye for Larvae from Oceanus magazine

- What Other Tales Can Coral Skeletons Tell? from Oceanus magazine

- Molecular Ecology & Evolution Lab at WHOI