The story of “Little Alvin” and the lost H-bomb

How the famed submersible found a lost hydrogen bomb in the Mediterranean Sea during the height of the Cold War

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Francisco Simo Orts was just about to raise his shrimp nets when the sky exploded.

It was the morning of January 17, 1966, at the height of the Cold War, and Orts' boat, the Manuela, floated five miles off the southern coast of Spain. Up above, a U.S. Air Force B-52 bomber flying at 31,000 feet had collided with a KC-135 tanker in an attempt to refuel, ripping through the KC-135's underbelly. Orts later told Navy officials that just after the explosion, he saw an airman parachute down into the ocean.

The tanker was completely destroyed in the accident, and as the bomber began to break apart, four B28 hydrogen bombs with 1.1 megaton warheads spilled from the sky and drifted toward the sleepy rural village of Palomares, Spain. In the aftermath, American servicemen searched the tomato fields and pastures, combing the scrubby terrain for the unarmed bombs. Three of the two-ton silver tubes turned up in the weeks that followed. But mysteriously, the fourth hydrogen bomb was nowhere to be found.

American servicemen in Palomares, Spain during the land search for the bombs. (Image courtesy of National Archives)

Meanwhile, Navy officials struggled to square Orts' account of a parachuting airman with the facts: all the crewmembers of both planes-dead or alive-had been accounted for. The officials soon realized that what the fisherman had witnessed wasn't a human being at all. It was the missing H-bomb, attached to a partially-deployed parachute.

Philip Meyers, now an 80-year-old professor emeritus of oceanography at the University of Michigan's Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, assisted in the subsequent underwater bomb search and recovery effort as an Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) officer. At the time, he was stationed at US Naval Air Facility Sigonella in Sicily, Italy. "The fisherman saw the thing hit the water with a trailing parachute that wasn't fully open," Meyers says. "[He] knew its rough location, but he didn't have the specific details of the bomb's location that could enable finding it with modern navigation systems."

The bomb, however, had to be recovered. "It was a very diplomatically-sensitive point," Meyers says. "The United States and Spain had a careful agreement that the U.S. could have Air Force and Navy bases in Spain, on the condition that there would be no nuclear weapons on or over Spanish territory."

The nature of the diplomatic agreement triggered the Navy to initiate an intensive underwater search for the missing weapon. "We're not looking for a needle in a haystack," said Rear Admiral William S. Guest, commander of the Navy's recovery task force at the time. "It's like looking for the eye of a needle in a field full of haystacks in the dark."

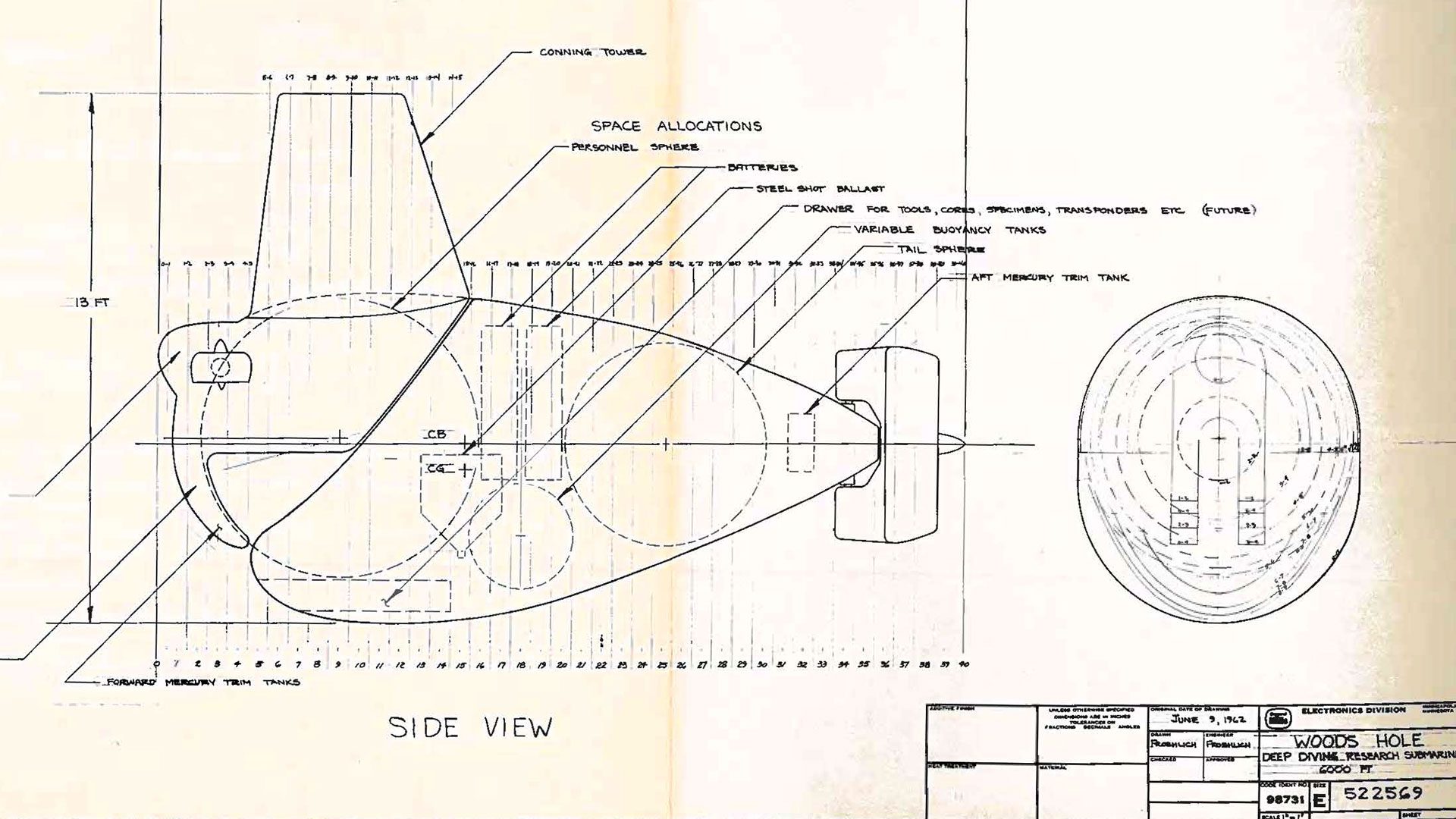

Officers began dropping probes into the ocean to look for the bomb. Weeks passed and the instruments detected nothing. So, at the end of January, the Navy enlisted the Human-Occupied Vehicle (HOV) Alvin submersible to assist in the search. The sub was just two years old at that point and was going through an overhaul by engineers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), which had been operating it for the Navy. But duty called, so the overhaul would have to wait.

"We typically think of Alvin as a scientific vehicle, but in the early days, it was more of a government vehicle," says Brett Freiburger, the Institution archivist for WHOI. "So despite it being a period of downtime for the sub and the crew, Alvin was called into service and had to be sent out immediately."

On February 1st, the sub was transported to Otis Air Force Base in Falmouth, Mass., loaded onto a cargo plane, and airlifted to Rota, Spain, for what would be its inaugural search and recovery mission. Two weeks later, Alvin plunged into the Mediterranean to begin the search. On board were Chief Pilot William O. Rainnie, who helped design and build the sub, engineer Marvin J. McCamis, and pilot Valentine P. Wilson.

Alvin is deployed from its tender, R/V Lulu, off the US Navy dock landing ship USS Plymouth Rock (LDS-29). (Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The sub began making a series of daily dives to depths of 3,000 feet, but the bomb didn't turn up. Visibility was tough, and didn't exceed 30 feet during most dives.

Rainnie, however, focused on the bright side. In a field operations memo, he wrote, "Alvin now commenced a series of five consecutive daily dives that breaks all records, even in shallow water, and exceeded even our fondest hopes for reliable performance." He commented on the steep canyon slopes the crew had encountered, some approaching 70 degrees, and added, "We are really getting to be experienced underwater mountain climbers!"

Meanwhile, tensions on land ran high. Thousands of Spaniards staged an anti-American demonstration at the US Embassy in Madrid, demanding that all American bases in Spain be closed. To make matters worse, the Soviets had an electronic monitoring ship lurking in the area and officials feared they might try to recover the bomb themselves.

Finally, on March 1st, the Alvin pilots spotted a track that the bomb had likely made after it skidded into the seabed. The crew followed the track over the next few weeks of dives until one day, as Alvin was inching down a 2,500-foot slope, a cylindrical object surrounded by a white parachute came into view.

Alvin's first glimpse at the lost H-bomb on the seafloor, covered by its parachute. (Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

There it was, the missing H-bomb. Against all odds, they'd found it.

But their work had only begun. Now the Alvin team and the Navy had to figure out how to pull the bomb to the surface. Meyers and his team were working on the USNS Mizar (AGOR-11), a Naval research ship, where they jury-rigged a recovery system for the bomb. "It was very elegant: a hook fabricated onsite from heavy sheet aluminum attached to 3,000 feet of nylon line," Meyers says.

Alvin took the system down through the Mizar's moon pool-an opening through the deck and bottom of the ship-and attached the line to the bomb's parachute. The crew began reeling it in. But there was a problem. Because the chute had been partially deployed, it spread out and slowed the upward motion of the bomb as it was hauled toward the surface. The load was too much for the aluminum hook, which bent under the weight and lost its hold, sending the bomb back down to the seafloor, out of sight. "The pilot and co-pilot must have been sweating bullets," Meyers says.

The Alvin was back at square one, though this time the crew had a better sense of where the bomb might have landed. Several weeks later, they found it once more. It had slid down a steep slope and come to rest at 2,800 feet, roughly 300 feet deeper than before. The crew once more attempted to recover the bomb, but the parachute flared up from the force of air generated by Alvin's propeller and nearly blanketed the vehicle. The submersible thrust away just on time, avoiding entanglement and the possibility of Alvin not being able to surface.

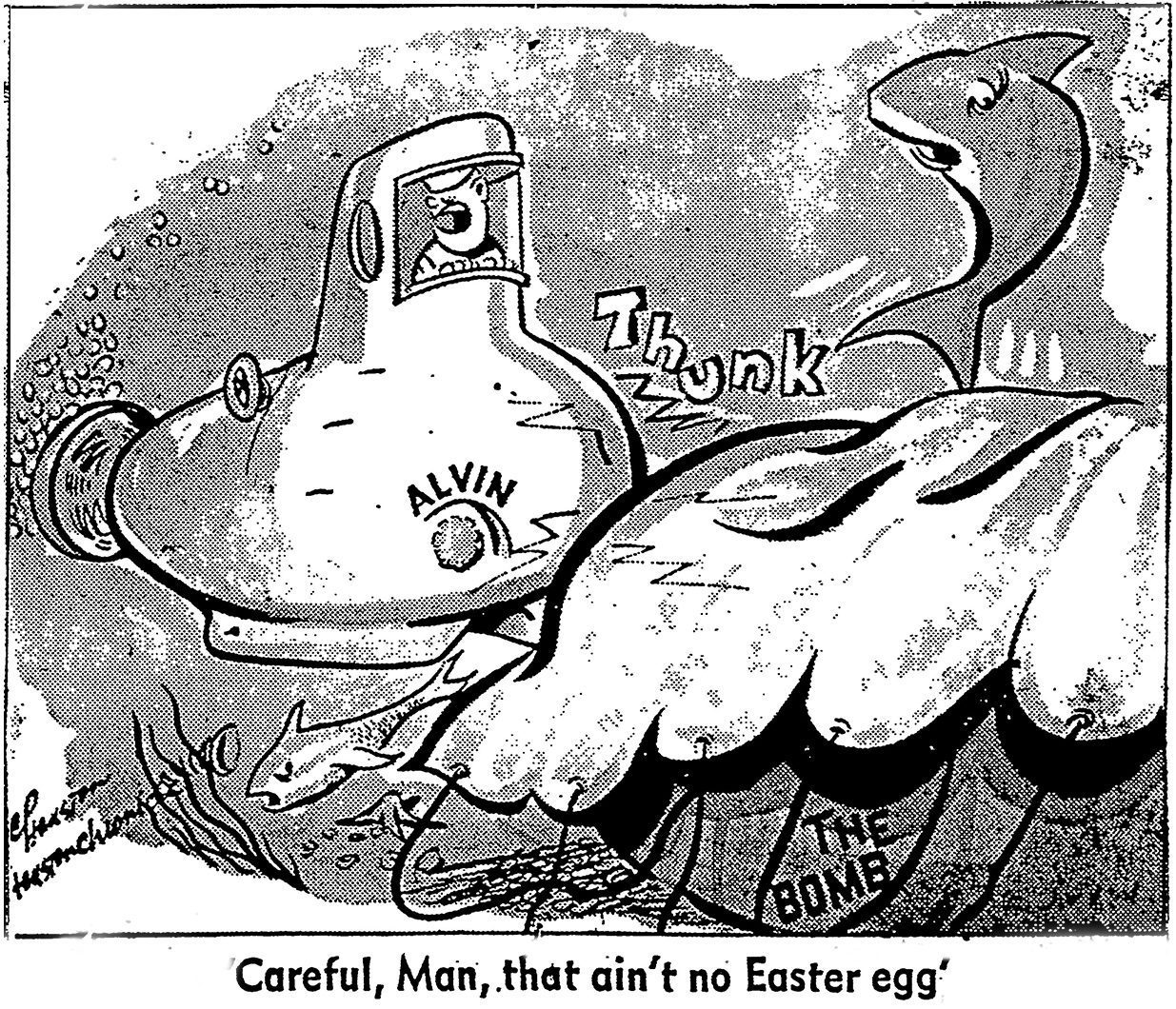

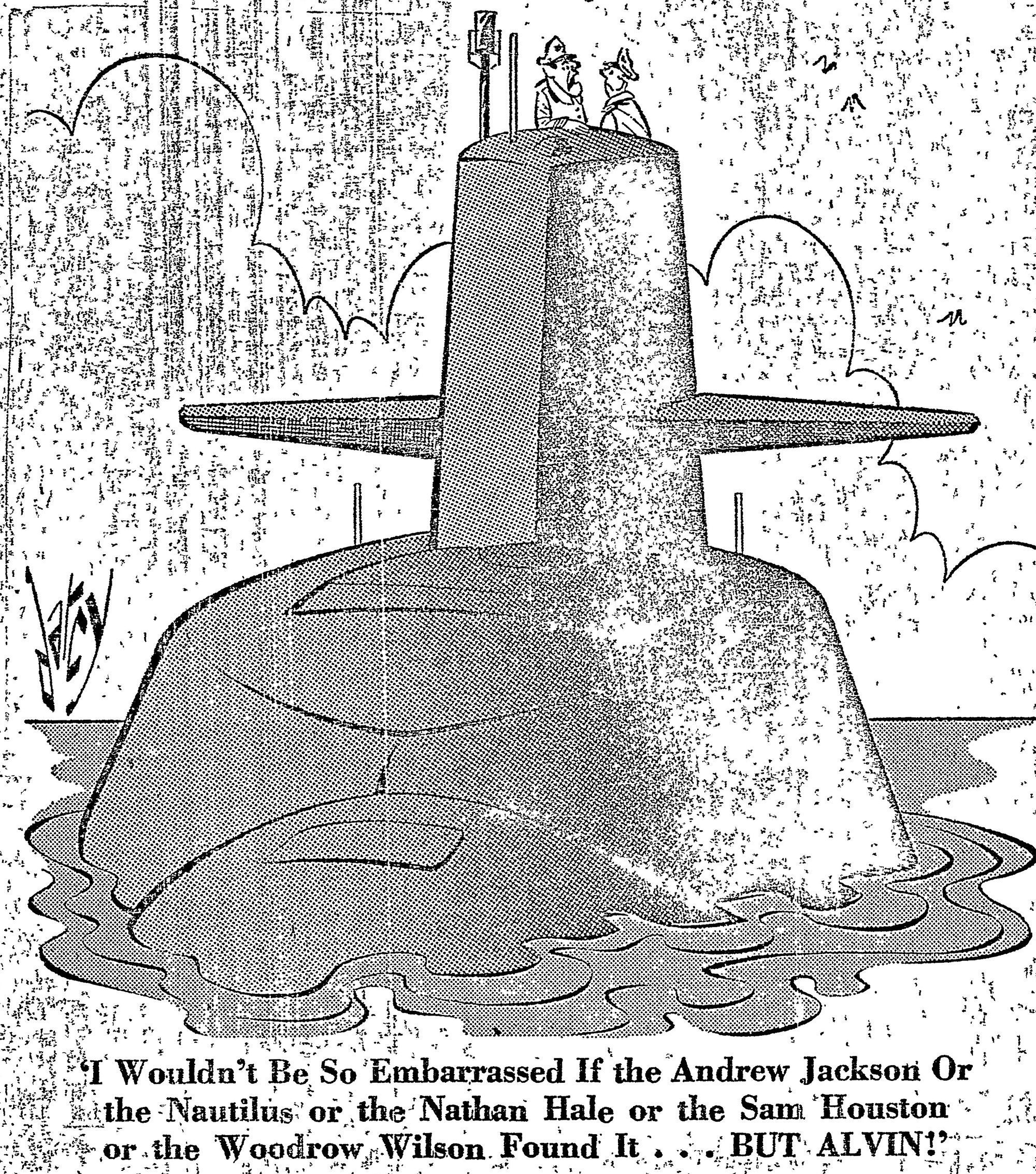

Newspaper cartoons from the Houston Chronicle (left) and the Houston Post (right) following the successful search and recovery of the lost hydrogen bomb in 1966. (Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

In early April, the bomb was finally brought to the surface by a Navy CURV (cable-controlled underwater recovery vehicle). Interestingly, CURV was able to recover the bomb only because the vehicle had become entangled in the parachute lines, allowing the vehicle to drag it up. At that point, the bomb had spent 80 days on the ocean floor. Alvin had performed 34 dives, totaling more than 220 hours below surface.

Yet “Little Alvin” (as newspaper headlines referred to it) made it through the entire operation with only minor mechanical breakdowns and suffered no failures. This was perhaps due to the overhaul and “debugging” the sub had been in the midst of when it was called into service.

In fact, the bomb operation ultimately improved Alvin’s design. In a memo dated April 29, 1966, WHOI submarine electronics technician William ‘Skip’ Marquet wrote: “Our recent Spanish operation highlighted our obvious lack of a semi-portable and operational navigation system for Alvin. We have now had sufficient operating experience with Alvin to define our requirements realistically and with awareness of the basic problems.”

More than half-a-century has passed since the saga of the lost H-bomb. At the time, it was the most extensive underwater search in history. Since then, Alvin has been overhauled more than a dozen times and its depth rating has gone from 6,000 feet (1,828 meters) to 14,764 feet (4,500 meters). Following additional tests in 2022, the submersible will be certified to a staggering 21,325 feet (6,500 meters). These improvements may make the 1960s version of Alvin sound primitive, but at the time, the underwater vehicle was anything but.

“When the sub arrived in Spain, I had to walk over to see it up close and to touch it,” Meyers says. “It was really something to marvel over.”