Are Pollutants Disrupting Marine Ecosystems?

A WHOI researcher stands up for the spineless invertebrates in coastal waters

Ask people to name some animals—any animals—and they will give you a long list. But chances are, all the animals will have one thing in common: a spine.

The animals that people think of—mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and birds—constitute only about 5 percent of the animal diversity on Earth. The other 97 percent are invertebrate species; hundreds of thousands, or perhaps millions of species that we largely ignore—to their peril and our own, said Tim Verslycke, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Researchers are now finding that some chemicals, especially pesticides, cause unexpected and unintentional harm to many invertebrate species that play essential roles in marine ecosystems and food webs, Verslycke said. These chemicals also may pose threats to crustaceans that humans love to eat: lobsters, crabs, and shrimp.

Invertebrates include both insects and crustaceans, which diverged long ago into separate branches on the evolutionary tree. But the two retain many fundamental biological mechanisms that have stood the tests of time and evolution and proved effective and beneficial.

Insects and crustaceans are both arthropods, which in addition to jointed limbs, share another common trait: They use the same hormones to carry out a wide range of crucial biological functions, ranging from molting, egg production, embryonic development, and sexual maturation, to energy metabolism, and even limb regeneration. So an insecticide targeted to disrupt hormones that help mosquitoes develop could easily disrupt other essential biological functions in crustaceans, Verslycke said.

Take methoprene, for example, a pesticide widely used to kill mosquito larvae and prevent mosquito-borne illnesses such as West Nile virus. It works by mimicking and disrupting insect hormones, Verslycke said.

“These pesticides are hardly toxic or effective in vertebrates, because vertebrates don’t have these hormones,” he said. “What we’ve been able to show, however, is that they are very effective against other non-targeted animals that do have these hormones, such as crustaceans and other coastal invertebrate populations. The fact that most invertebrates use the same hormones to regulate very different processes makes it a bigger problem.”

Overlooked environmental threats

In the lab, Verslycke and colleagues have found that very low levels of exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals, in just the parts-per-billion range, have resulted in impaired embryonic development, molting, and growth in marine crustaceans, and they have found such low levels of these chemicals in coastal waters, sediments, and crustaceans. In ongoing field studies, Verslycke is also investigating the levels and effects of hormone-disruptors in local coastal invertebrate populations.

Recently, for example, New England fishermen have observed female lobsters molting their shells before they have carried their eggs to term. “This obviously means something is going wrong with their hormone regulation,” Verslycke said. He believes that increased chemical exposure in coastal waters may be a factor fueling the recent outbreak of lobster shell disease, which has run rampant in southern New England waters and led to large declines in lobster catches (see "A Mysterious Disease Afflicts Lobster Shells").

More than half the nation’s population lives near coastal waters, which provide valuable commercial and recreational resources, as well as an essential source of food. About 1 billion pounds of conventional pesticides are used each year in the United States to control insects, weeds, and other pests. These pesticides, from both agricultural and urban sources, run off into nearby estuaries and coastal waters that are critical in the life cycles of important marine fish and crustacean species.

“Industry is looking to regulatory agencies to come up with the tests they need to do to prove whether these chemicals pose environmental threats,” Verslycke said.

Screening for harmful chemicals

“Tim has certainly been a voice for this issue,” said Jesse Meiller, a scientist at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. He has been skilled at bringing together colleagues from academia, industry, and governmental agencies to work on the problem, she said.

In 1996, Congress passed the Food Quality Protection Act, which directed the EPA to develop a program to identify substances with the potential to disrupt human hormonal systems, Meiller said. In June, the EPA’s Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program published a draft initial list of pesticides, commercial chemicals, and environmental contaminants. The program is also developing and validating tests to determine the effects and effective dose levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Verslycke argues that any comprehensive program that seeks to protect our environment from the potential harmful effects of chemicals that disrupt hormones should include invertebrates, and not just vertebrates, as is now mostly the case.

“As a society, people are generally a little more worried about things that directly affect humans,” he said. “So it’s a little harder to get funding to look at effects in some obscure marine copepod species rather than studying similar effects in humans. However, from an ecological perspective that doesn’t make sense.”

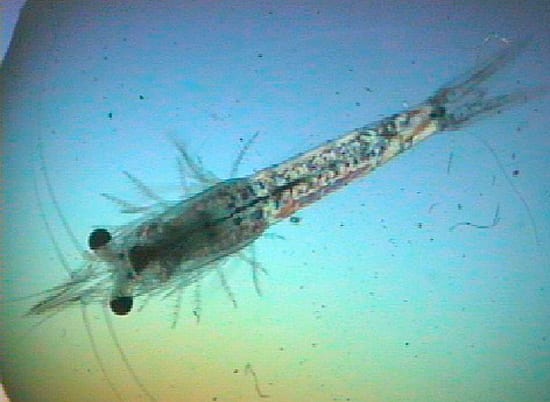

Copepods, for instance, are tiny, abundant marine crustaceans that constitute perhaps the largest animal biomass on Earth. They are the major food source for small fish, whales, seabirds, and other crustaceans in the word’s oceans.

Crustaceous canaries?

Verslycke is doing his part by developing new invertebrate-based assays to detect low, but still potentially harmful, levels of certain chemicals in water and sediment samples. His research has contributed to our basic knowledge of hormonal systems and processes in long-overlooked marine invertebrate species such as copepods and a group of small crustaceans called mysids.

“To say something is disrupted, you must first know what’s normal,” he said.

The EPA is presently considering using mysids in its Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program as a model invertebrate species to test for the toxic effects of chemicals, Meiller said. Mysids are an important link in the food chain, especially in estuaries, she said, and they are generally more sensitive to toxic substances than other species. Verslycke says mysids could act as canaries in a coal mine to indicate when marine environments are being exposed to endocrine disruptors that could affect other invertebrates as well.

Verslycke first discovered this area of research while studying for an undergraduate and then a master’s degree in bioscience engineering and environmental technology at Ghent University in Belgium, where he investigated the way certain chemicals can disrupt the hormones of freshwater snails.

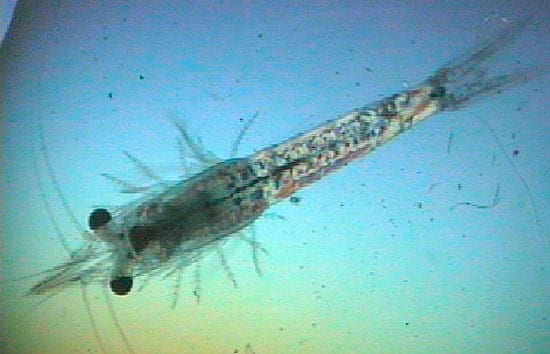

After receiving his master’s in 1999, he followed his interest in marine species downstream to the Scheldt estuary in The Netherlands, where he conducted his doctoral research, also at Ghent University, on chemically induced hormone disruption in mysids.

Verslycke’s research has been funded by the Ocean Life Institute at WHOI, the Belgian-American Educational Foundation, MIT Sea Grant, and the New England Lobster Research Initiative administered by Rhode Island Sea Grant.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Chemicals, especially pesticides, may be causing unexpected and unintentional harm to many invertebrate species that play essential roles in marine ecosystems and food webs, says WHOI biologist Tim Verslycke. (Courtesy of Tim Verslycke, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Small crustaceans called mysids, shown here swarming in the ocean, could act as canaries in a coal mine to indicate when marine environments are being exposed to chemicals that could affect other invertebrates as well, says Tim Verslycke. Adult mysids are between 10 to 30 millimeters long. (Photo courtesy of Tim Verslycke, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Verslycke began his research on hormonal disruption in invertebrates on Neomysis integer, a species of mysid common in European estuaries, which could also be used to test the susceptibility of invertebrates to potentially harmful chemicals. (Photo courtesy of Tim Verslycke, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Featured Researchers

See Also

- "Are We Still Forgetting the Other 95 Percent?" A commentary by Tim Verslycke on e.hormone, a Web site on environmental signaling research, hosted by the Center for Bioenvironmental Research at Tulane/Xavier Universities

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program

- Endocrine Disruptors from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences-National Institutes of Health

- European Union's Endocrine Disrupter website