I love the people I work with, and I like working with people in the field. Days in the office are nice, but when you have a group of scientists working together for days or weeks in these extreme conditions, you get to know each other really well. I laugh so hard in the field! You’re outside all day, and the days are often twice as long as any day in the office, but that doesn’t matter because you're actually in the place that you think about every other month of the year. You feel part of something much bigger than when you sit in an office.

Then you come back! I get really excited about all the data, but at the same time, I miss the people I work with, the excitement of collecting data, the mental and physical exhaustion at the end of a long field day, and the conversations on our two-hour truck rides.

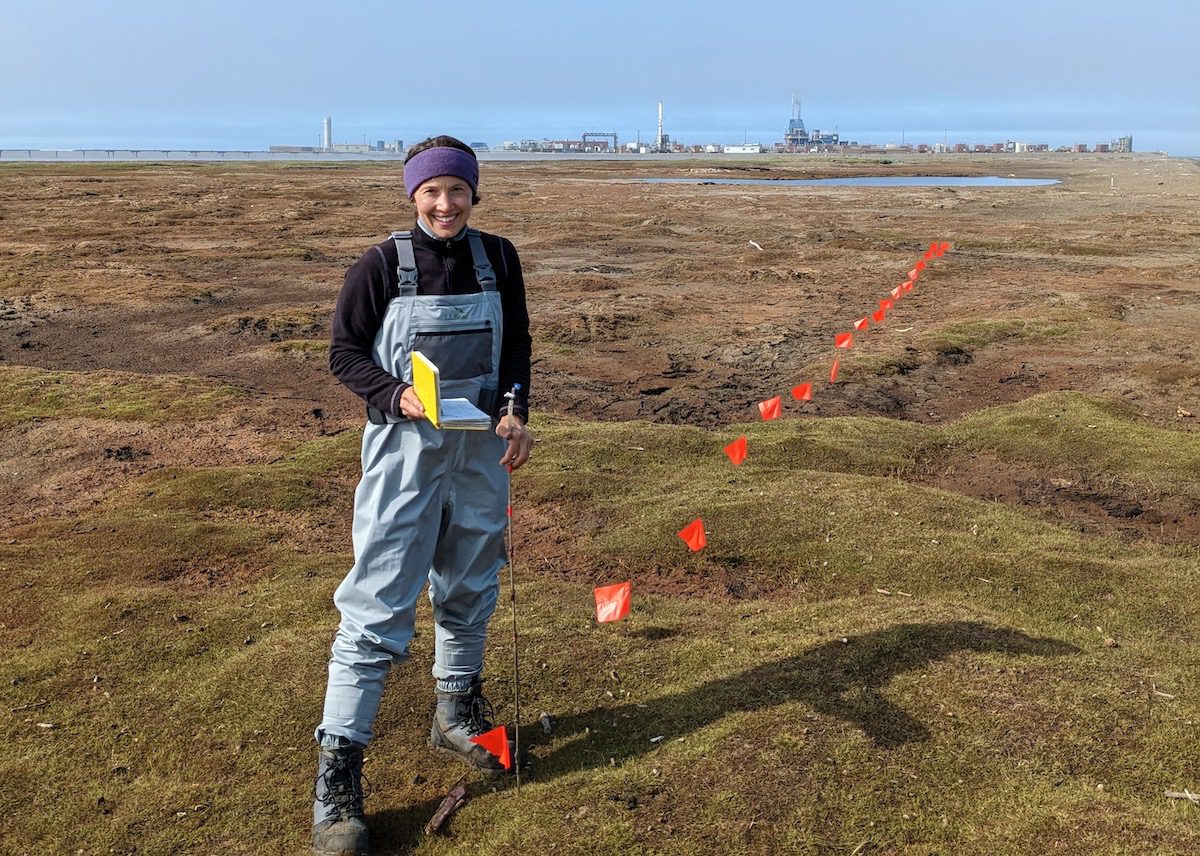

The North Slope of Alaska is uniquely beautiful in that it's so flat and this vast tundra with ponds and low grass everywhere you look. You drive for hours and hours, seeing nothing but tundra. And then you get to the site that you're studying on the coast. And it's so small, I can't help thinking about where my research fits into this perspective. On a really clear day, you can see to the Brooks Range. Sometimes, you can even see the reflection of the sea ice in the sky.

Being there allows you to see things differently or think of things that you would not have thought about if you were just looking at data or Google Earth imagery.

I study how Arctic coastlines are changing. Because it’s so difficult to get to the northern coast of Alaska, remote sensing tools like satellites are helpful for capturing what’s happening at the surface. But it’s impossible to see what’s going on underground. So when I’m in the field, I install groundwater monitoring wells (which are essentially slotted PVC pipes) to study how water moves. I also conduct geophysical surveys to “see” subsurface characteristics, like groundwater salinity and depth to permafrost, to pick out differences between healthy and degraded tundra. In the healthy tundra, we hit permafrost after digging about 30 cm (about a foot). But in the degraded tundra, the groundwater is salty, and you don’t hit permafrost until about a meter (3.3 feet) down.

There’s a marked lull after returning from field work. It’s something like post-birthday blues or the void you feel after coming back from a wonderful vacation. Even after just a week or two in the field, it can be difficult to adjust back to office life. Field work is unlike any other aspect of the job. There's just something compelling about being somewhere so different and having a purpose to be there.