Message Bottled in an Email

A long-lost legacy of ocean research resurfaces

Every once in a while, a curious email floating through cyberspace will land unexpectedly in your inbox, like a message in a bottle.

Such an email arrived this week. This one actually contained a message in a bottle—one that had floated through the Atlantic and back in time to the year before I was born.

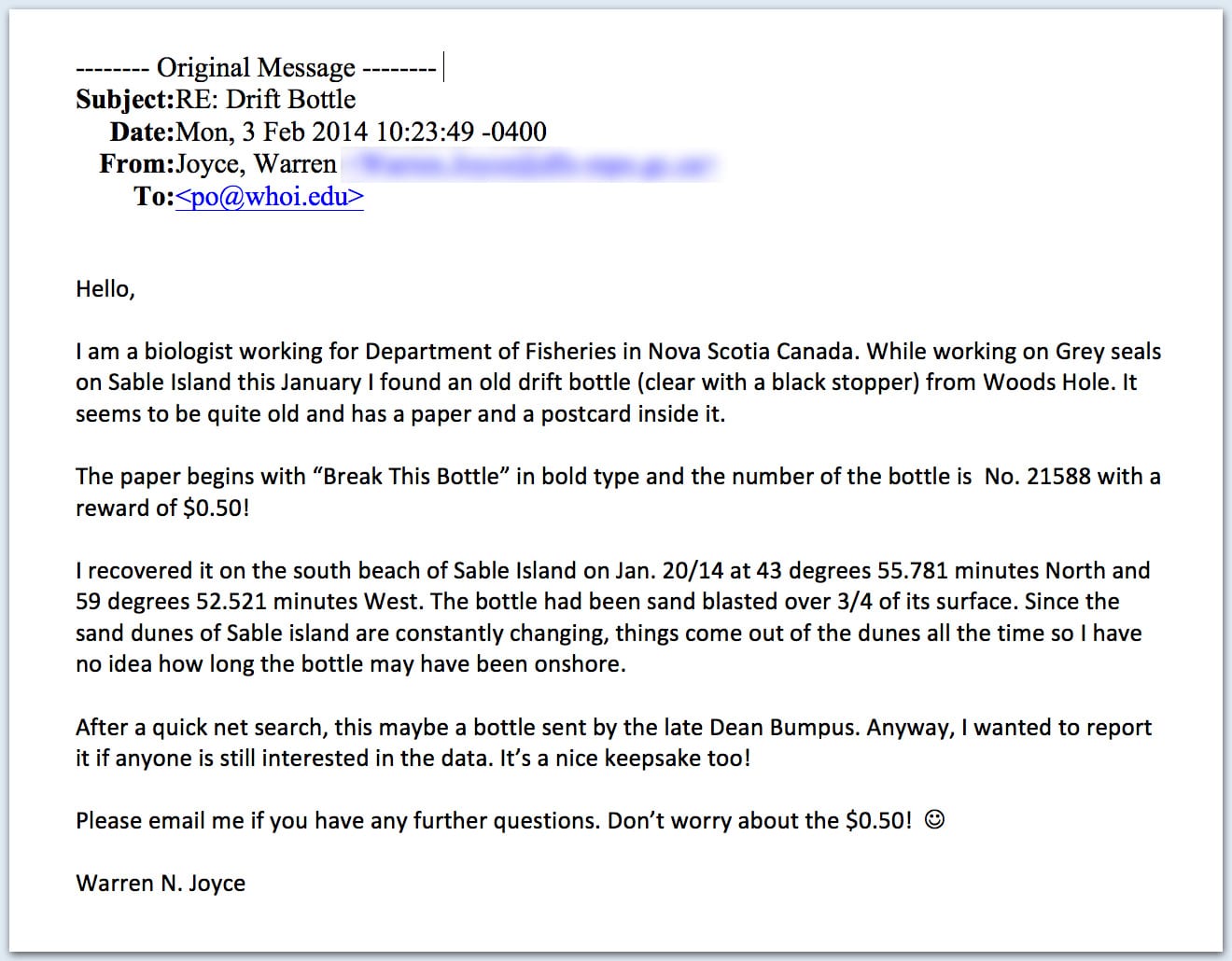

Here’s the email that begins the tale:

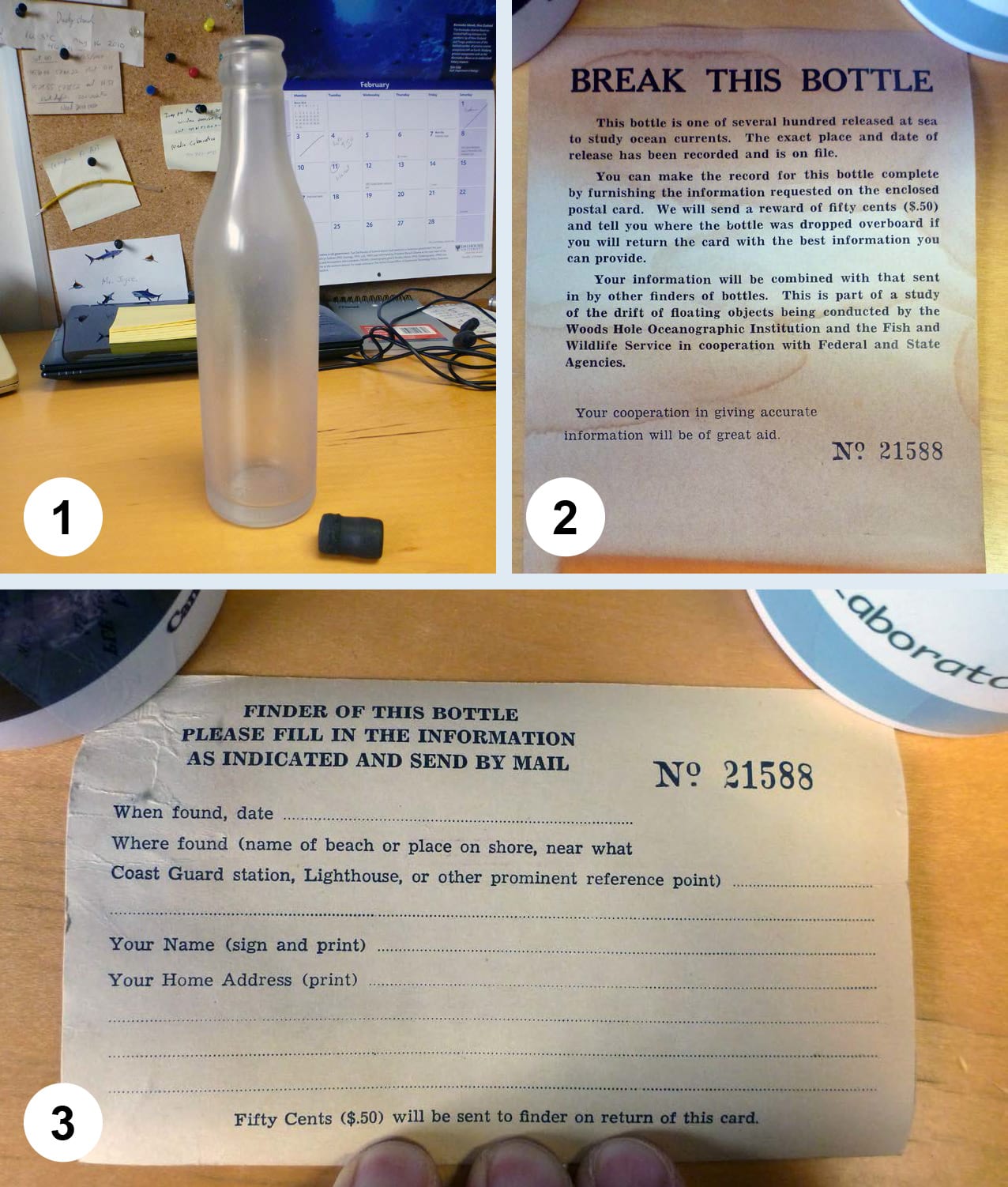

Joyce sent photos of the bottle (1), the note inside (2) and the postcard (3).

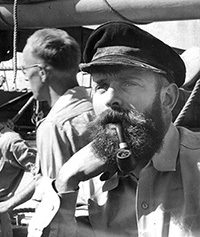

From 1939 to 1941, aboard the WHOI research vessel Atlantis, Bump helped conduct what many consider the first comprehensive surveys of the marine life of Georges Bank; biologists still find them valuable today.

During World War II Bump, Allyn Vine (after whom the submersible Alvin is named), and other WHOI scientists worked closely with the U.S. submarine fleet to instruct submariners on how to use the bathythermograph, an instrument designed by WHOI researchers that measured temperature and density gradients in the ocean. Using bathythermographs, submariners could avoid acoustic detection by enemy surface vessels. That’s Bump, below right, leading a class to train Navy submariners. The WHOI group was commended by the U.S. Navy for the many lives it helped to save.

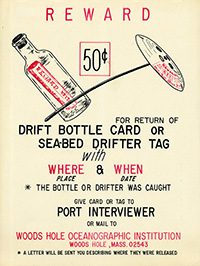

In September 1959, Bump issued a memo that conveyed a great deal about the frugal, enterprising, collaborative, and lively characteristics of oceanographers of the era: “All hands are respectfully requested (until further notice) to bring their dead soldiers to the lab and deposit them in the box just inside the gate. Whiskey, rum, beer, wine or champagne bottles will be used to make drift bottles. Any clean bottles — 8 oz to one quart in size will be gratefully received. Bottoms Up!”

According to Bumpus’ 2002 obituary, “Although very simple devices, both the surface and seabed drifters contributed significant information on the surface and bottom circulation along the continental shelf of eastern North America, sometimes to the dismay of others with much more sophisticated technology.”

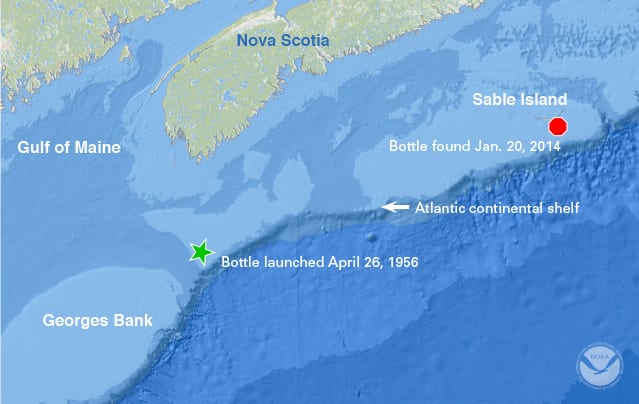

WHOI archivist Dave Sherman tracked down the bottle that Joyce found on Sable Island: No. 21588. It was one of 12 released from the research vessel Albatross III on April 26, 1956, at 8:30 p.m. at 42°18’6″N, 65°30’6″W, not far off Nova Scotia. Three bottles from this batch were recovered later the same year—two in Nova Scotia and one in Eastham on Cape Cod.

Given its sandblasted appearance, perhaps No. 21588 came ashore on Sable Island also in 1956, some 300 miles away from its release point, and remained buried and buffeted by dunes until now.

“The island is also famous for more than 350 shipwrecks since the late 1500s,” Joyce said. “Its location in the middle of shipping routes and fishing grounds has made it a major hazard to seagoing vessels.”

Sable Island also makes an ideal hangout for grey seals. Almost every year since 2005, Joyce has assisted on a research project on their population dynamics, going to the island for a month in January when the seals mate and give birth.

Meanwhile, I did some Internet detective work of my own to find Joyce’s address. I just sent him this JFK half-dollar (even if postage costs to Canada now exceed that!). WHOI must keep its word, and that’s a bargain price for a good story. Besides, what goes around should come around.

Related Articles

- Healing on the High Seas

- Music for the Ocean

- Breakthroughs below the surface

- An Oceanographer’s Atlas

- A cozy crusade

- 5 WHOI women making waves in ocean science and engineering

- Five idioms for ocean lovers

- Accessible Oceans

- Diverse Voices From Our Maritime Past

- Five books WHOI researchers are reading right now

- On the high seas

- Future Voices: how kids view our ocean in the coming decades

- Who is Peter de Menocal? A Conversation with WHOI’s new President & Director

- To sail, not to drift

- Looking into the Future