Who is Peter de Menocal? A Conversation with WHOI’s new President & Director

On October 1st, Dr. Peter de Menocal assumed the role of President & Director of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the 11th person to hold that title since the Institution was founded in 1930. In a wide-ranging conversation, we meet the man and the scientist—and get a glimpse of what WHOI’s future may hold under his leadership.

Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

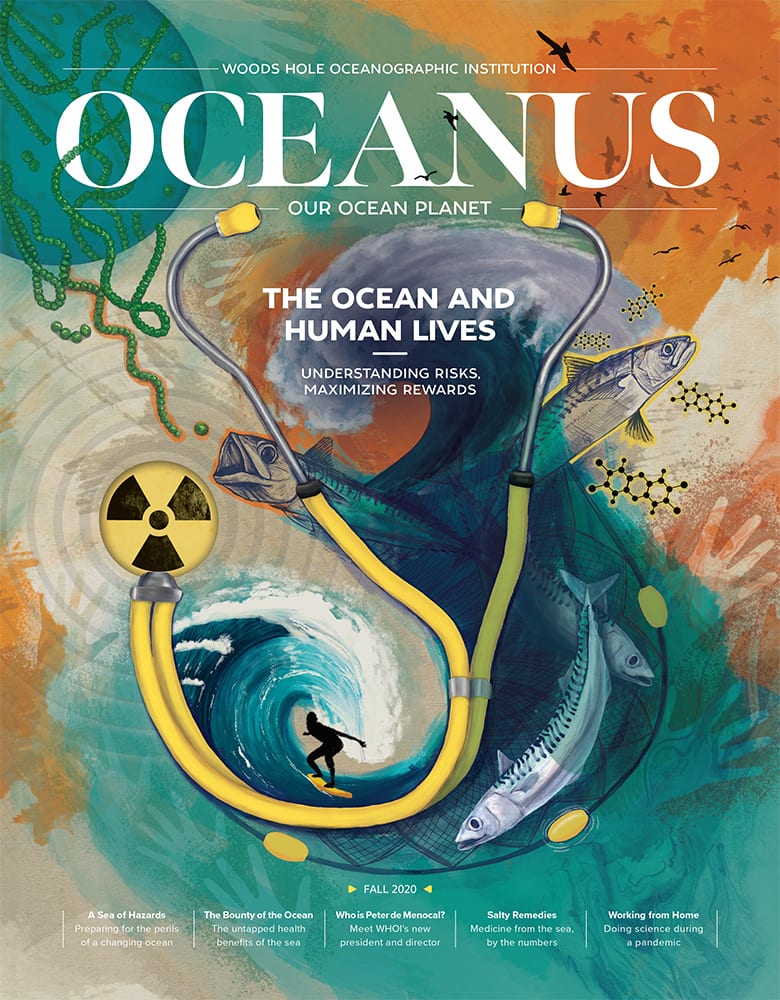

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2020

This article printed in Oceanus Fall 2020

Oceanus: Welcome to WHOI!

De Menocal: Thank you very much.

Oceanus: If you don't mind, let's start at the beginning: Where did you grow up, and what aspects of your childhood eventually led you to a career as a marine geologist and climate scientist?

De Menocal: I grew up in Rye, New York, in what was then a small, quiet suburb just north of New York City. I have always been drawn to the ocean, even from childhood. My family and I would visit my grandparents who had retired and moved to Nantucket in 1945, when it really was the remote and eponymous "far-away island." I remember asking endless questions about the sea and marveling at its immensity and power. But it would be many years before I realized that I could turn my curiosity about the ocean into a career.

Photo courtesy of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University

Funny enough, my professional connection to the sea began at WHOI. At the time, I was a clueless but optimistic studio-art and math major at St. Lawrence University in far upstate New York, near the Canadian border. On a crisp day in the spring of 1979, I hitchhiked south to visit a friend on Cape Cod. My last ride dropped me off in front of the Quissett campus, where stern signs saying "Secure Area: No Trespassing" beckoned me to investigate.

I reached the Clark Building, walked inside, and was stunned by what I saw: gleaming labs, computer centers, and gaggles of students everywhere. A big bear-paw of a hand grabbed my shoulder and asked in a booming voice, "Son, can I help you?" The hand and voice belonged-not to a security guard, as I first thought-but to famed marine geologist Charley Hollister. He pulled me into his office, and I spent the next several hours listening to his tales of going to sea, traveling the world, building scientific instruments, and conducting oceanographic research. I was riveted. When I walked out of Clark that day, I knew what I wanted to do with my life.

Oceanus: You have had a long and successful career at Columbia University. What were some of the highlights of your time there?

De Menocal: I came up from the mailroom, as it were. I entered as a graduate student in 1987, studying marine geology and paleoceanography at the Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, one of best Earth science research labs. These were heady, exciting times at Columbia, as climate science was really taking off. After I finished my Ph.D. in 1992, I spent seven years as a soft-money research scientist and gained a deep, personal understanding of the benefits and challenges of grant-funded research. I was invited to join the Columbia faculty in 1999, was selected as department chair, and eventually became Dean of Science, managing 240 faculty across nine science departments in the School of Arts and Sciences. It was quite a ride!

I think the experience that has most prepared me to take on a leadership role at WHOI was founding and directing Columbia's Center for Climate and Life. Faced with an urgent need for climate solutions-and declining federal funding for climate science-I wanted to develop a new funding model that incentivized scientists to pursue high-risk, high-value research to accelerate innovation. With about $15 million in new philanthropic support, I started a prestigious Fellows program that freed scientists to think deeply and creatively about developing actionable knowledge for the public good. The model relies on private sector partnerships. It is scalable. And it works.

Oceanus: Why come to WHOI, and why now?

De Menocal: The simple answer is that WHOI is the best and most distinguished oceanographic institution in the world. But more importantly is that they have-or we have-a strategic distinctiveness that sets us apart from every other institution: this marriage of engineering and technology with scientific inquiry. It's that connection between a search for basic knowledge on the scientific side with developing really innovative tools on the engineering side that will invite and enable the discovery we need today.

If you think about the challenges facing humanity in the coming decade-climate change, carbon management, growing food, water, and energy needs-they all connect directly to our changing oceans. So, we'll need a much better understanding and monitoring of these changes and how they affect things we fundamentally care about. And it's going to require innovations in marine engineering and technology: big data and ocean data science, remote observations, and an "internet of things" in the ocean.

It's going to take a discovery approach that is unlike anything we've ever done before. And that can only happen in a place like WHOI.

Oceanus: Along with advancing science and engineering, WHOI is committed to education-academically, but also more broadly, through public engagement with the ocean. In your opinion, how important are ocean education and literacy to WHOI's mission, and why?

De Menocal: WHOI's educational efforts are broad-based and essential to the Institution's mission. Through its graduate and post-doctoral programs, undergraduate summer student fellowships, and K-12 outreach, WHOI is educating and inspiring the next generation of ocean engineers and scientists.

Since 1968, WHOI has partnered with MIT to form one of the premier marine science and engineering graduate programs in the world-the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography, Applied Science & Engineering. The Joint Program gives students unmatched access to instruments, ships, technology, and instruction and mentoring from some of the world's best ocean researchers and innovators. In 2018, the program marked its 50th year, having graduated more than 1,000 scientists and engineers, many of whom have gone on to make valuable contributions-in research, but also in teaching, government, industry, and the Navy. Additionally, WHOI supports early-career scientists through its post-doctoral scholar and fellow appointments. And at the undergraduate level, WHOI's summer programs give aspiring oceanographers of diverse backgrounds the opportunity to work alongside world-class researchers and gain hands-on experience in the lab, in the field, and at sea.

WHOI also has a role to play in K-12 STEM outreach. Ocean education for K-12 students is a triple-win for society, fostering better health, equity, and sustainability. It builds a society that understands the value of our greatest planetary resource and life support system-the ocean. And it increases diversity in the sciences by inspiring bright young minds from underrepresented groups to pursue ocean science careers.

Lastly, our path to a sustainable future on this increasingly crowded planet begins with the call for a healthy, stable, and protected ocean. Winning hearts and minds to protect the oceans-so they will continue to protect us-requires more than just our amazing science, engineering, and discovery. It takes an outward-facing, forward-looking effort to communicate to the public and to policymakers how the oceans are changing-in ways that directly impact our health, economy, and security. We can use our convening power to drive greater public engagement on societally-relevant issues. Recent research shows that every dollar invested in resilience saves six dollars in future cost. Science-informed action protects us from outcomes we really want to avoid.

Oceanus: As you mentioned, your own academic background and research is in marine geology and paleoceanography. Have you been to sea?

De Menocal: Yes-mostly on WHOI ships! I've been on the R/V Oceanus, and on the R/V Knorr-a couple of times on each. My field work has involved deep-sea sediment coring, typically piston coring, in the North Atlantic and Arabian Sea. My most recent seagoing work has been mainly off the coasts of East and West Africa.

One of the areas that I've worked on is trying to understand changes in African vegetation and climate linked to human evolution. And in particular, looking at the shifting hydro-climate-basically, the rain and the drought cycles-that have occurred in the geologic past. The instrumental record only gets us back a hundred years, but if we want to go back thousands of years, or tens of thousands of years, we have to use the ocean sediments as a proxy or archive.

Oceanus: What was your most memorable at-sea experience?

De Menocal: I was on a sediment-coring cruise on a Dutch ship, the R/V Pelagia, in the Gulf of Aden-this was only three months before 9/11. Pirate activity was on the rise, and to avoid being detected as we sailed along the Somali coast, we had to shut down all the ship's navigation lights and radio communications. The only way we had to get updates about ship attacks was via transmissions on a weather fax. We'd get this chunka, chunka, chunka, chunka of the fax machine, churning out a map of where the latest attacks were happening. Pirate attacks were getting more frequent, but no one knew why-9/11 hadn't happened yet. And it was wild, because some of the attack coordinates were right near the coring sites we were steaming toward.

There we were, on this incredibly slow diesel electric ship that was doing maybe ten knots. I mean, we were just chugging along in these dangerous waters in the black of night with no navigation lights. We had regular drills-like, if we were to be boarded, what would we do? You have to lock this door, and hide in this chain locker...It was a little like Captain Phillips. We went through several weeks of this before we finally passed through the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb-the entrance to the Red Sea-and into the safety of Saudi Arabian waters. The incident was written up in The Atlantic more than a decade later, when we published the results of our research in Science. The lead author on that paper was actually my former post-doc Jessica Tierney, then a paleoclimatologist at WHOI.

Oceanus: The latest issue of Oceanus magazine is about the risks and rewards of the ocean. We weren't thinking about pirates (!), but about the ocean's role in human health. How do you see humanity's relationship to the ocean?

Photo courtesy of Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University

De Menocal: The Earth appears as a blue marble from space. With more than 70 percent of our planet's surface covered by ocean, it's no surprise that human health is directly linked to ocean health. The ocean is our planet's life support system. It is the primary driver of Earth's climate system, weather, and water cycle; it feeds and sustains billions, including many of the world's poorest people; and it makes life as we know it possible. Most importantly for people today is that the oceans are in transition: surface water temperatures, sea ice, fisheries, and the health of coral reefs are all shifting away from historical norms. We still have time to avoid bad outcomes, but that window of opportunity is narrowing.

Oceanus: Science research is founded on analyzing data-observations, facts-and reaching conclusions in an unbiased way. But given the importance of the ocean to human health, should a research institution such as WHOI play a role in advocating for ocean sustainability and stewardship?

De Menocal: Our primary role is to provide expert, scientifically-based guidance on issues of societal importance. The role of a scientific institution such as WHOI is to advance the state of knowledge so that factual, informed decision-making can prevail above convenient opinion. As such, we are advocates for science and discovery as they inform knowledge, policy, and practice in service of the common good. But we should refrain from specific advocacy.

Oceanus: The American Geophysical Union recently released a strategic plan in which they signaled a shift away from pure basic research toward greater focus on solutions to the problems facing society. "AGU members," the plan states, "have the potential, opportunity and responsibility not only to advance further discovery but also to accelerate our efforts to address societal challenges in the coming century." What are your thoughts on this shift toward solutions thinking, and what are the implications for WHOI?

De Menocal: Ultimately, WHOI's work must be rooted in strong, fundamental science. I don't think we can lose sight of that as we search for solutions. But I do believe we are in a time of deep societal need that calls upon WHOI scientists and engineers to step up and lead, pursuing use-inspired basic science that can accelerate solutions. By "use-inspired basic science," I mean research that both seeks a fundamental understanding of scientific problems and also has value for society. The phrase was coined by Donald Stokes in his book Pasteur's Quadrant-the work of scientist Louis Pasteur is thought to exemplify research that bridges the gap between "basic" and "applied." That's where we need to be.

Pursuing use-inspired basic science invites scientists and engineers to take on really difficult, risky, but critically important questions that have useful answers for humanity. We need to incentivize that kind of creative, risky thinking to address the urgency and the magnitude of the changes-warming, ice melt, sea level rise, and their repercussions and impacts-that we know are ahead of us.

Oceanus: The best engineering and science often grows out of collaborations and teamwork. Do you see collaboration across disciplines and among institutions as a means of addressing large-scale problems facing the world?

De Menocal: The challenges we face are bigger than any one institution. Moreover, the problems require transdisciplinary partnerships and solutions that engage the private sector. I believe in a shared mission approach that aligns scientific, technological, philanthropic, policy, and business partners towards a common, problem-solving goal. We can learn from successful solutions to big, complex environmental challenges such as acid rain or ozone depletion: Science frames the debate, public engagement provides urgency, and public-private sector partnerships build viable, science-based solutions.

Oceanus: Staying with the subject of collaborations and teamwork-ocean science has a very poor track record when it comes to diversity, equity, and inclusion, despite the fact that studies have shown that diverse teams, in which everyone's contributions are valued, consistently outperform homogeneous ones. What actions will you take to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion at WHOI, at all levels?

De Menocal: Well, we're already looking into hiring a diversity officer. One of the first things I want to do is to have somebody join me at the directorate level to lead our activities and our diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. I mean, it's just fundamentally important. I've had the really great fortune of having been at a place like Columbia, where they're very serious about it. They committed hundreds of millions of dollars to diversifying faculty. It's not easy. There is systematic bias. But what I can say is that having been at Columbia for 33 years, I did see a department with no women go to 40 percent women. I did see the hiring of underrepresented minorities increase dramatically in the sciences, from a near-zero baseline.

There's so much work to do. I suppose it's daunting. But it's so gratifying to see change. A lot of it comes down to the courage to lead and just committing to it. And a lot of it has to do with having resources and applying them, because it does require targeted investment. But Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) work is absolutely one of my top priorities.

Oceanus: What other challenges do you expect to face at WHOI?

De Menocal: Meeting 1,100 people in my first month (laughs)? But that's a big part of what I want to do, is to get to know our people.

I think the biggest challenge-not for me, really, but for oceanography-is finding our path forward to use our knowledge to make a difference in the world. Because the world needs us. The question is how we, as an oceanographic community, will meet this challenge and adjust our way of doing science, of funding science, of going after big audacious problems, with the kind of commitment and resolve that's needed. I believe we can. And WHOI has a very special role to play in this-I think it's a chance for us to be part of something bigger than ourselves.