Seabirds Face Risks from Climate Change

Scientists who study birds in remote regions also confront danger

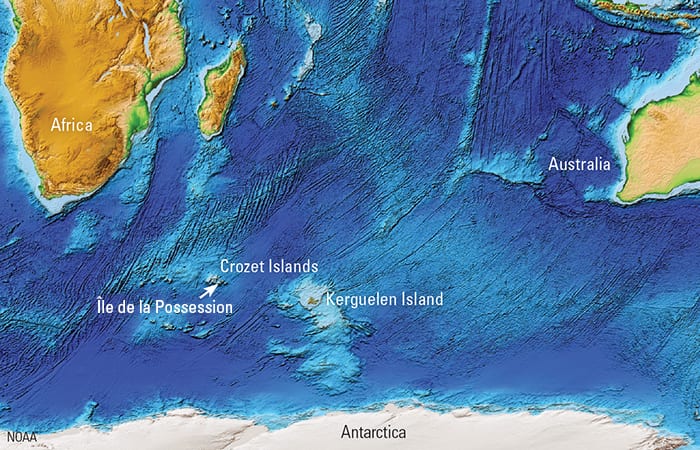

The research expedition ended in near-disaster. Stephanie Jenouvrier, aboard the ship Marion Dufresne II, was heading to the Southern Ocean to study seabirds. On Nov. 14, 2012, while making a stopover at tiny windswept Ile de la Possession in the Crozet Islands, about 1,800 miles from Cape Town, South Africa, the Dufresne struck a shoal that opened an 82-foot breach along its hull. The ship’s bow thruster was disabled, and watertight compartments filled with icy seawater.

“We felt like the ship was sinking,” said Jenouvrier, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “If the captain had not realized our trajectory was wrong, we would have hit with the front of the ship and sunk right away. We were lucky.”

The 110 people aboard the wounded ship were helicoptered to a research station on the island, which already housed 50. They were stranded.

“We left for the trip very confident,” Jenouvrier said. But there they were on Ile de la Possession, waiting for rescue.

Jenouvrier and colleagues had been headed to French-held Kerguelen Island to gather information on black-browed albatross, wandering albatross, Macaroni Penguin and other seabirds— animals at the top of their Southern Ocean food chain. As such, Jenouvrier said, “seabirds are sentinels of climate change.”

Impacts of climate change are already affecting some regions at Earth’s poles, as well as the creatures that dwell there. In the Arctic, polar bears that depend on dwindling sea ice are now endangered. In Antarctica, seabirds also depend on ice: Seabirds eat fish, which eat shrimplike crustaceans called krill. The krill eat algae, and the algae grow underneath sea ice.

Jenouvrier is investigating how seabirds will fare in the face of climate change. To do that, she needs data on all the myriad interlocking environmental factors that affect seabirds’ lifestyles.

Winners and losers

Seabirds fly very long distances to forage at sea, but they return to nesting sites on land to breed. Many seabirds mate for life sometimes live and reproduce into their fifth or sixth decades.

Studying climate change requires a long-term perspective, so the researchers make multiple trips to seabird nesting sites, just as the birds do. The French researchers she collaborates with have been gathering information on these species for a half-century in colonies where pairs return year after year. They weigh and count seabirds, count eggs, band chicks and equip birds with satellite tags to record the ranges and duration of their foraging flights.

“In Antarctica you cannot be alone, so we do this as a team,” Jenouvrier said. “And I need the data from other researchers for my own study, because for modeling their responses to climate change it’s very valuable for me to understand what they eat, where they go, how much time they forage.”

She integrates the information from fieldwork, data on sea ice and other environmental variables, species’ ecology, and climate projections from the International Panel on Climate Change into mathematical models to project seabirds’ responses to climate change.

Jenouvrier and WHOI biologist Hal Caswell previously used models to predict the future of emperor penguin populations in one part of Antarctica. Emperors breed annually, and need the presence of sea ice to breed and feed. They calculated that emperor penguins there had a 42 percent chance of declining by more than 90 percent by 2100

In seabirds’ projected futures, “there are winners and losers,” Jenouvrier said.

Just as wild turkeys and chickadees have different sizes, lifespans, and reproduction rates, and fit into their woodland environment differently, so it is with penguins and petrels in Antarctica—different life strategies create differences in species’ flexibility to deal with rapid climate change.

In contrast to penguins, petrels might be able to cope with climate change. Jenouvrier found that they can skip breeding—for instance, in a year when warming conditions diminish sea ice and decrease food resources. Long lives give petrels time to reproduce in subsequent years, so the skipped year wouldn’t seriously affect a bird’s lifetime number of offspring.

The tale of the hexacopter

Jenouvrier brought along a new technological tool: miniature, electric, remotely operated aerial vehicles with a camera and six rotors—“hexacopters”— developed in WHOI scientist Hanumant Singh’s lab. Jenouvrier trained for two months to use it at WHOI, then trained workers in France to fly it before the Dufresne left for the Southern Ocean.

“The aim was to have workers use the hexacopter to count penguins every year,” Jenouvrier said. “Ground counts are hard, because the birds stand so close together. Aerial photos are better, but with a helicopter you can’t go close and scare the birds. The hexacopter is simpler, cheaper, and ‘greener,’ or less polluting.”

But they never made it to Kerguelen.

Stuck on 58-square-mile Ile de la Possession, the researchers tripled up in the space at Alfred Faure station, and had days to wait until a rescue ship from the coast of Africa could reach them.

“We slept in the library, we slept in the gym, in labs, closets, everywhere. We showered in the bath used for cleaning penguins. But we had time, so we made a mission with the hexacopter, still training.”

The biggest challenge to using the hexacopter is wind,” she said. “Crozet Island is extremely windy, and there were only a few hours when the wind dropped enough to fly it.” Jenouvrier left the hexacopter with workers on Crozet. After she had gone they flew it. The wind came up, and it crashed.

“That’s how science goes, sometimes,” she said. “We did not give up on the hexacopter! It is still there, and the people I trained have put it together to use again.”

Ten days after they were marooned on Ile de la Possession, another French ship arrived from South Africa to rescue the researchers, and they didn’t reach land again for another week. Their 2012 field season was over, but Jenouvrier’s work continues. In 2014 she will invite international policy specialists and scientists to a Morss Colloquium at WHOI to discuss conservation strategies for polar species endangered by climate change.

“The aim of this is to move beyond borders for conservation,” she said. “We need a new paradigm of global cooperation and need to move quicker to mitigate the impacts of climate change on polar seabirds.”

Stephanie Jenouvrier’s work is supported by the National Science Foundation and the WHOI Ocean Life Institute. Development of the hexacopter was supported by the WHOI Access to the Sea Fund.

Slideshow

Slideshow

WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier, holding an Antarctic snow petrel, is investigating the impacts of climate change on seabirds. She incorporates data on seabird's lifestyles with myriad interlocking environmental factors to construct mathematical models that can project how seabirds' populations will fare in the future. (Photo courtesy of Stephanie Jenouvrier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier, holding an Antarctic snow petrel, is investigating the impacts of climate change on seabirds. She incorporates data on seabird's lifestyles with myriad interlocking environmental factors to construct mathematical models that can project how seabirds' populations will fare in the future. (Photo courtesy of Stephanie Jenouvrier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- Many seabirds nest on tiny sub-Antarctic islands such as the Crozet and Kerguelen Islands. Stephanie Jenouvrier collaborates with French research teams that have monitored these bird colonies for decades. In Novenber 2012 she made an unexpected stay on Île de la Possession in the southern Indian Ocean. (Eric Taylor, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Seabirds such as these black-browed albatrosses are iconic sights in the Southern Ocean, but they face an uncertain future. These far-ranging birds mate for life, sometimes living and reproducing into their fifth decade and beyond. Climate change is already affecting some polar regions. WHOI biologist Stephanie Jenouvrier is working to understand how seabirds will respond to climate-influenced changes in the many interlocking parts of their ecosystem, from sea ice, winds, and currents to the availability of food, distances birds must fly to forage, and reproduction rates. (Photo by Charles Bost, CEBC, CNRC, France)

- The "hexacopter"—an electric, remotely operated aerial vehicle developed by WHOI scientist Hanumant Singh—is an innovative new technology that will help researchers monitor bird populations. The hexacopter carries a camera to take aerial images of birds on the ground without frightening them with a helicopter's noise or polluting the air. Jenouvrier tested the new tool on an expedition in 2012. (Photo by Stephanie Jenouvrier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)