Round Up the Unusual Suspects

DNA forensics identifies unknown deep-sea organisms

Annette Govindarajan is a kind of marine detective. She tracks down animals living throughout the ocean, including those in the ocean twilight zone—the vast, dimly lit, largely unexplored region 650 to 3,280 feet (200 to 1,000 meters) below the surface—which still harbors many species yet to be discovered and identified.

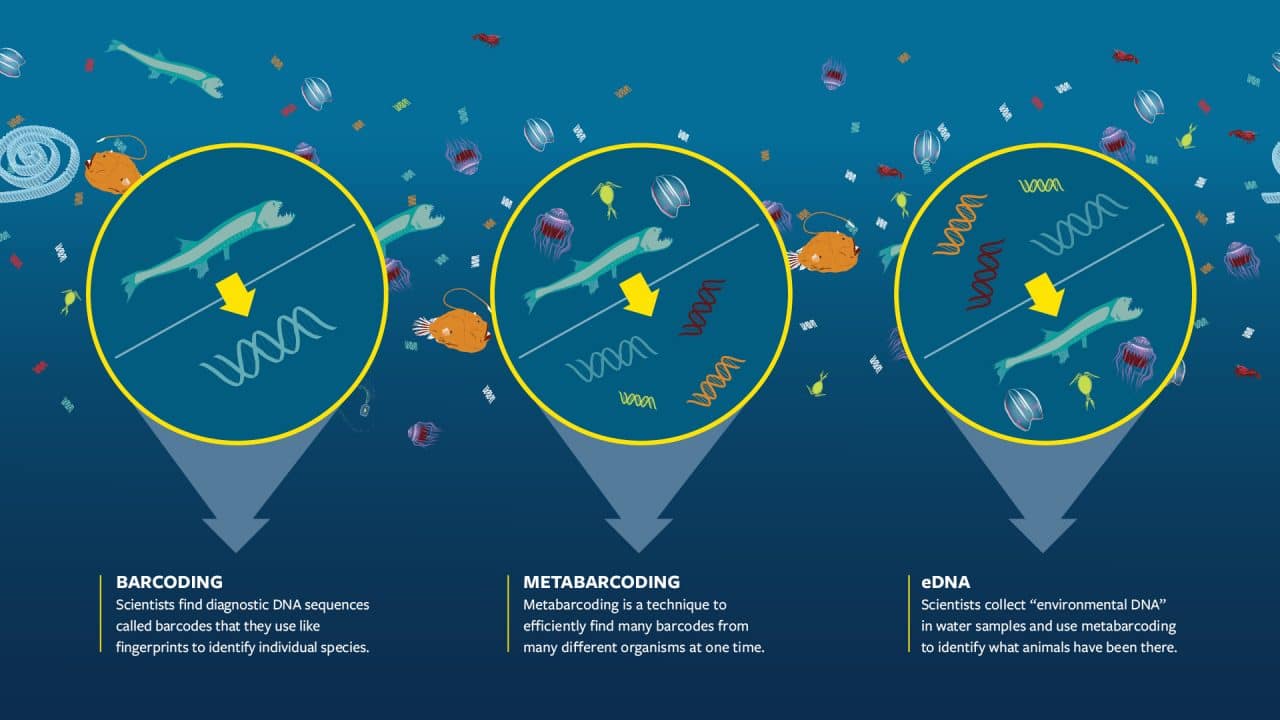

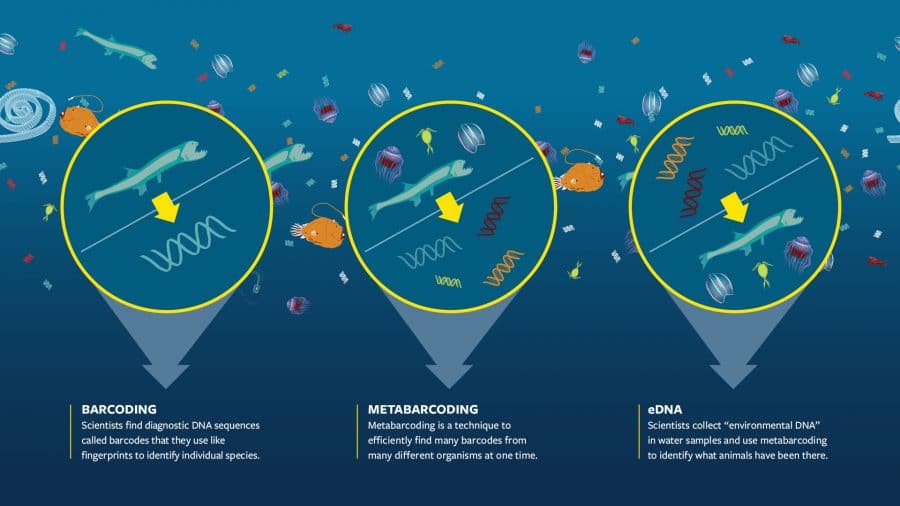

As it is for many crime detectives today, the key to her forensics is DNA, said Govindarajan, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. When WHOI scientists bring up a netful of animals, Govindarajan sequences key parts of their genes, called DNA barcodes, which are distinct to individual species. It’s something like taking the fingerprints of suspects. Police compare their suspects’ fingerprints to those in a database of known criminals. Similarly, by comparing newfound barcodes to those in a database of known species, Govindarajan can identify organisms from just their genes.

The technique works well if the suspect—in this case, a twilight zone animal—has been “fingerprinted” before, and its DNA barcode is already in the database. But most twilight zone species are not in the database, so part of Govindarajan’s mission is to take the genetic fingerprints of as many species as she can.

But to even begin to identify all the different species in a region as vast as the ocean twilight zone, Govindarajan needs to be able to analyze a whole lot of DNA all at once—something like simultaneously fingerprinting all the suspects in a lineup, not just one at a time. To do that, she uses metabarcoding—a technology to sequence the genetic information from many organisms at the same time.

“Instead of picking out individual microscopic animals from a plankton net, you take the entire net contents, grind it up, and get back, say, hundreds of thousands of barcode sequences,” Govindarajan said. “You can identify most of the plankton community in one shot.”

Metabarcoding is a step up, but what Govindarajan really wants to be able to do is walk into a big, dark room—or region of the ocean—and identify her suspects by the fingerprints they have left behind. The oceanographic equivalent is analyzing seawater samples to detect environmental DNA, or eDNA—the genetic information that twilight zone species leave behind as they swim through the ocean.

Govindarajan put eDNA fingerprinting to the test in the summer of 2018, on the first cruise of WHOI’s ocean twilight zone project. Aboard NOAA’s research vessel Henry B. Bigelow, she collected water samples from the twilight zone, and in the ship’s lab, analyzed them for free-floating genetic information.

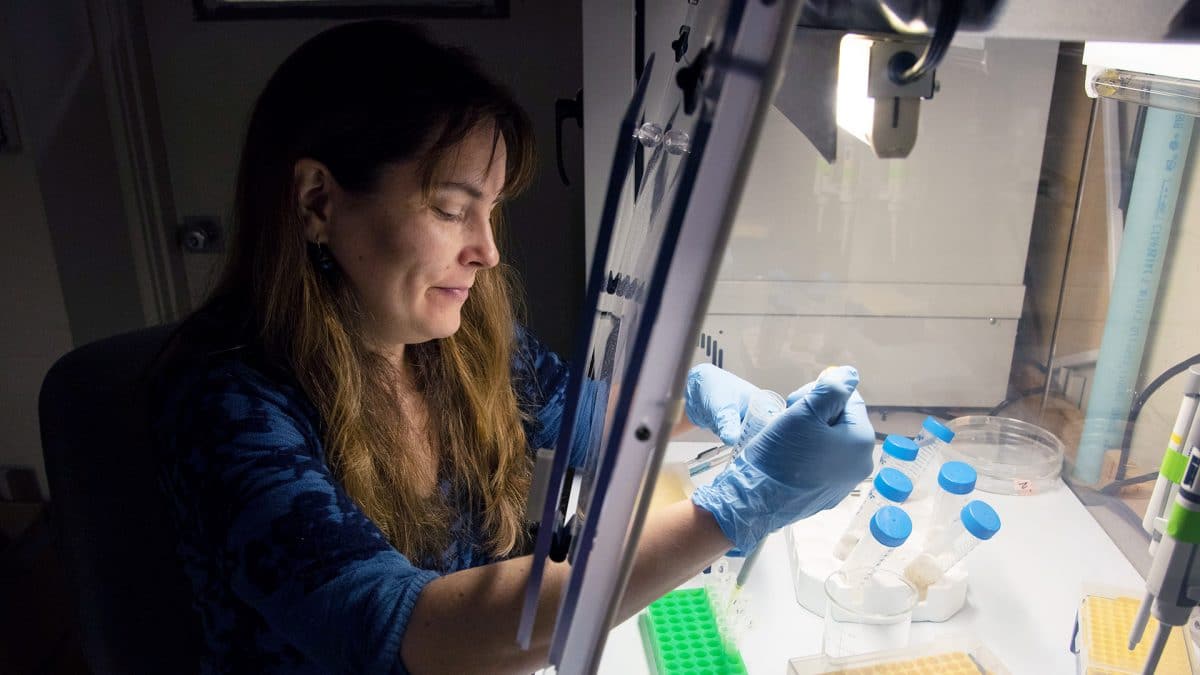

But just like delicate fingerprints, eDNA is easily contaminated.

“We had to be very careful on the ship,” Govindarajan said. “We set up a dedicated work area. We wiped it with bleach every day. We went through a new pair of gloves every few minutes! We took every precaution.”

Another challenge, however, is degradation of the evidence. Even in the short interval between collecting a sample and analyzing it in the ship’s lab, the eDNA starts to decay.

A better approach, she says, is to collect eDNA directly in the water, using a sampler on an underwater vehicle. Govindarajan tried out this method on the Bigelow cruise, using the Deep-See—WHOI’s new, large, ship-towed platform that combines high-resolution camera systems, sonars, environmental sensors, and a water sampler.

“By collecting the water and preserving it in situ,” Govindarajan said, “you don’t have to worry about degradation, and there are fewer steps where your sample can become contaminated, because there’s less handling.”

In addition, scientists can decide when to collect samples, depending on what the vehicle’s acoustic and imaging systems are “seeing.”

A new WHOI vehicle being developed called Mesobot will excel at collecting eDNA in situ. The small, free-swimming robot will carry a device known as a SUPR (Suspended Particulate Rosette) sampler, which was designed at WHOI by geochemist and engineer Chip Breier, now at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. The SUPR sampler will be able to filter up to 12 samples during a single twilight zone mission and preserve them immediately after collection.

Funding for this research came from the WHOI Ocean Life Institute and The Audacious Project.

From the Series

Related Articles

- An immersive twilight zone exhibit

- Can the twilight zone be fished responsibly?

- Five big discoveries from WHOI’s Ocean Twilight Zone Project

- Experts gather to discuss the ocean’s super-powered carbon pump

- A new way to track marine snow ‘blizzards’

- AI in the Ocean Twilight Zone

- Edie Widder: A light in the darkness

- How to speak “Ocean”

- In the Ocean Twilight Zone, Life Remains a Mystery