Edie Widder: A light in the darkness

By sharing her fascination with the luminous deep, explorer, author, and conservationist Edie Widder sheds light on why it matters.

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2022

This article printed in Oceanus Winter 2022

Edie Widder was dangling from a wire, 800 feet below the surface of the Santa Barbara Channel, when her life–and the course of her research–changed forever.

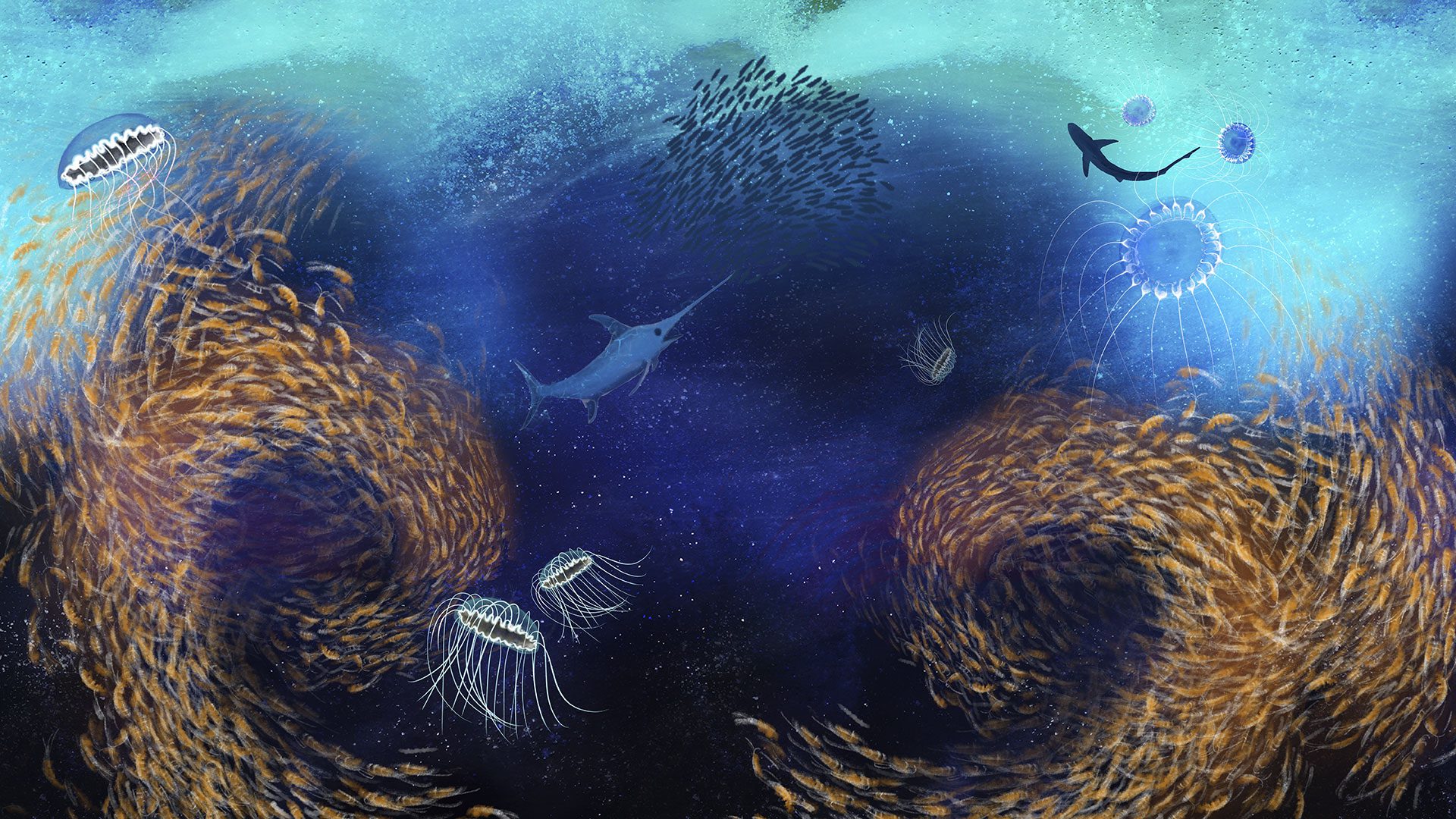

Glowing, flashing, and trailing lights filled the viewport dome of the deep-diving suit, lovingly dubbed The Wasp, that she was encased in. Though she had studied the phenomenon in the lab, Widder was finally witnessing the bioluminescent signals of thousands of marine creatures in their own mid-ocean habitat. Located roughly 200 to 2,000 meters (650 to 6,500 feet) deep, this area is known as the ocean twilight zone. In the vanishing absence of sunlight, life has somehow thrived in this region—and as a grad student, Widder thought it might have something to do with the fact that 90% of twilight zone inhabitants have evolved to make light on their own.

“Bioluminescence is one of the most interesting processes in the ocean. I just thought, ‘Why aren’t more people studying it?’” Widder told an audience of about 100 during a recent talk in Woods Hole. “I just couldn’t go back. I’ve been studying it ever since.”

Since that light-bulb moment in 1984, Widder has been studying—and sharing—the fascinating world of deep-sea bioluminescence. As a scientist with the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and later, as founder of the non-profit Ocean Research and Conservation Association, her research led to major discoveries about deep-sea ecology, including a new octopus species with bioluminescent suckers and the first video of a giant squid in the deep sea. Commissioned by the US Navy in 1981, a team led by Widder built the first deep-sea light meter capable of accurately measuring bioluminescent light in the ocean, which drew unwanted attention from crafty Soviet spies. Her work has been featured in countless documentaries, including the BBC’s Blue Planet II, and her TED talks have garnered millions of views.

There is no place to hide in the deep ocean, Widder points out, so animals take cover “at the edge of darkness” to keep safe. Over time, and independently of one another, many species evolved to see well in low light. They also evolved to produce light to hunt, confuse predators, and communicate. Many twilight zone inhabitants sport bioluminescent lights on their bellies, which counterilluminate the sunlight from above—helping them hide in plain sight from predators below. Some species, like lanternfish, have specific light patterns on their bodies that help them find mates from within their own species. And still others, like anglerfish, make use of bioluminescent bacteria to attract prey.

“Energy is not wasted in the deep ocean. The fact that so many animals make light tells you so much about how important it is.”

-Edie Widder

In her 2021 memoir, Below the Edge of Darkness, Widder weaves her personal story of overcoming blindness, fickle funding, and technological hurdles into a gripping, humorous tale. Throughout her career, Widder paid attention to how animals behave—and how she could use their adaptations to learn more about their world. Frustrated that noise and light from deep-sea submersibles was thwarting her ability to record bioluminescence, she developed a drop-camera system, dubbed the Eye-In-The-Sea, that took inspiration from two bioluminescent creatures. She modeled a lighting system after the stoplight loosejaw, one of the only creatures in the deep sea that can perceive “far red” light.

Atolla is a jellyfish common from midwater, about 500 meters deep—where there is still a small amount of sunlight, to bathyal depths of 4500 meters—far below the limit of sunlight's penetration. Where there is light, its red color looks black, making it hard to see. It also produces brilliant bioluminescence, possibly to frighten predators. (Photo by Larry Madin © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Taking a cue from this stealthy fish–which sports a red “sniper scope” under its eyes–she installed long-wavelength red LED lights on a frame outfitted with a hyper-sensitive camera. But in the massive, dark ocean, she needed a way to attract creatures to the camera’s field of view. That’s when she thought of the Atolla jellyfish, which flashes its extremely bright blue lights like an alarm when disturbed, attracting larger predators to eat the assailant. With blue LED lights arranged in a circular pattern embedded in epoxy, Widder created the “e-jelly” as an optical lure. With her far-red lighting system and the e-jelly, Widder became the first to record video evidence of a giant squid while filming a documentary off Japan in 2012. She would go on to devise increasingly advanced technologies to record giant squid and Humboldt squid behavior that revolutionized our thinking about these enormous, elusive predators.

Bioluminescence isn’t just a cool phenomenon that helps creatures survive in an extreme environment, says Widder. Glowing bacteria attached to the “marine snow” falling through the ocean entices creatures to eat the carbon-rich particles, cycling carbon through the ocean depths and keeping it out of the atmosphere. Bioluminescence also has applications in medicine, such as the green fluorescent protein (first obtained from a jellyfish) that illuminates cell processes and is extensively used as a biological tracer to study pathogens and cancer.

These applications are examples of why humanity should focus on exploring our ocean planet before turning to outer space, Widder told her Woods Hole audience. By sharing her fascination with the luminous deep, she hopes to shed light on why it matters.

“Our future on the planet depends on concentrating on what makes life possible, which means we need to be able to see life with new eyes,” Widder writes in her memoir. “If the purpose of life is to understand itself, then perhaps living light can help illuminate the path to that destination.”

The event, A Conversation with Edie Widder, was presented by The Yawkey Foundation as part of WHOI’s Dispatches from an Ocean Planet: A summer series of literature, film, and science.