Radioactivity Under the Beach?

Pollution from Fukushima disaster found in unexpected spot

Scientists have found a previously unsuspected place where radioactive material from the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant disaster has accumulated—in sands and brackish groundwater beneath beaches up to 60 miles away. The sands took up and retained radioactive cesium originating from the disaster in 2011 and have been slowly releasing it back to the ocean.

“No one is either exposed to, or drinks, these waters, and thus public health is not of primary concern here,” the scientists said in a study published in October 2017 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. But “this new and unanticipated pathway for the storage and release of radionuclides to the ocean should be taken into account in the management of coastal areas where nuclear power plants are situated.”

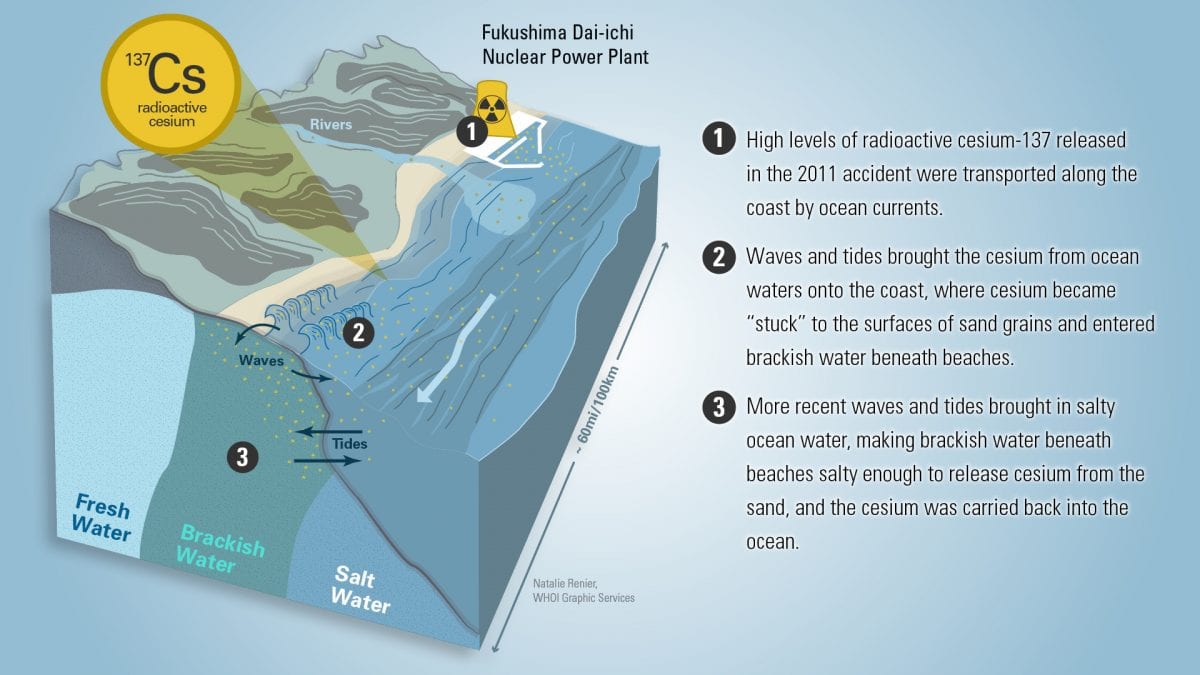

The research team—Virginie Sanial, Ken Buesseler, and Matthew Charette of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Seiya Nagao of Kanazawa University—hypothesize that high levels of radioactive cesium-137 released in 2011 were transported along the coast by ocean currents. Days and weeks after the accident, waves and tides brought the cesium in these highly contaminated waters onto the coast, where cesium became “stuck” to the surfaces of sand grains. Cesium-enriched sand resided on the beaches and in the brackish, slightly salty mixture of fresh water and salt water beneath the beaches.

But in salt water, cesium no longer “sticks” to the sand. So when more recent waves and tides brought in salty seawater from the ocean, the brackish water underneath the beaches became salty enough to release the cesium from the sand, and it was carried back into the ocean.

“No one expected that the highest levels of cesium in ocean water today would be found not in the harbor of the nuclear power plant, but in the groundwater many miles away below the beach sands,” Sanial said.

The team sampled eight beaches within 60 miles of the crippled Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant between 2013 and 2016. They plunged 3- to 7-foot-long tubes into the sand, pumped up underlying groundwater, and analyzed its cesium-137 content.

The researchers also conducted experiments on Japanese beach samples in the lab to demonstrate that cesium did indeed “stick” to sand grains and then lost their “stickiness” when they were flushed with salt water.

“It is as if the sands acted as a ‘sponge’ that was contaminated in 2011 and is only slowly being depleted,” Buesseler said.

“Only time will slowly remove the cesium from the sands as it naturally decays away and is washed out by seawater,” Sanial said.

“There are 440 operational nuclear reactors in the world, with approximately one-half situated along the coastline,” the scientists wrote. So this previously unknown, ongoing, and persistent source of contamination to coastal oceans “needs to be considered in nuclear power plant monitoring and scenarios involving future accidents.”

This research was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Deerbrook Charitable Trust, and the European Commission Seventh Framework Project “Coordination and implementation of a Pan-Europe Instrument for Radioecology.”