PlankZooka & SUPR-REMUS

Scientists develop new ways to sample tiny marine critters

Much of marine life begins as microscopic larvae—so tiny, delicate, and scattered in hard-to-reach parts of ocean that scientists have had a tough time illuminating this fundamental stage of life in the ocean.

To see what’s out there, scientists have had to rely on sampling by towing nets behind ships. But these traditional methods can’t cover a lot of territory or access shallow or deep areas of the ocean, and they often squish and muddle specimens they catch.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists developed two new plankton sampling devices (with superpowered names) that can be mounted on robotic undersea vehicles. PlankZooka can operate near the seafloor at deep depths, and SUPR-REMUS can collect larvae in constrained shallow waters.

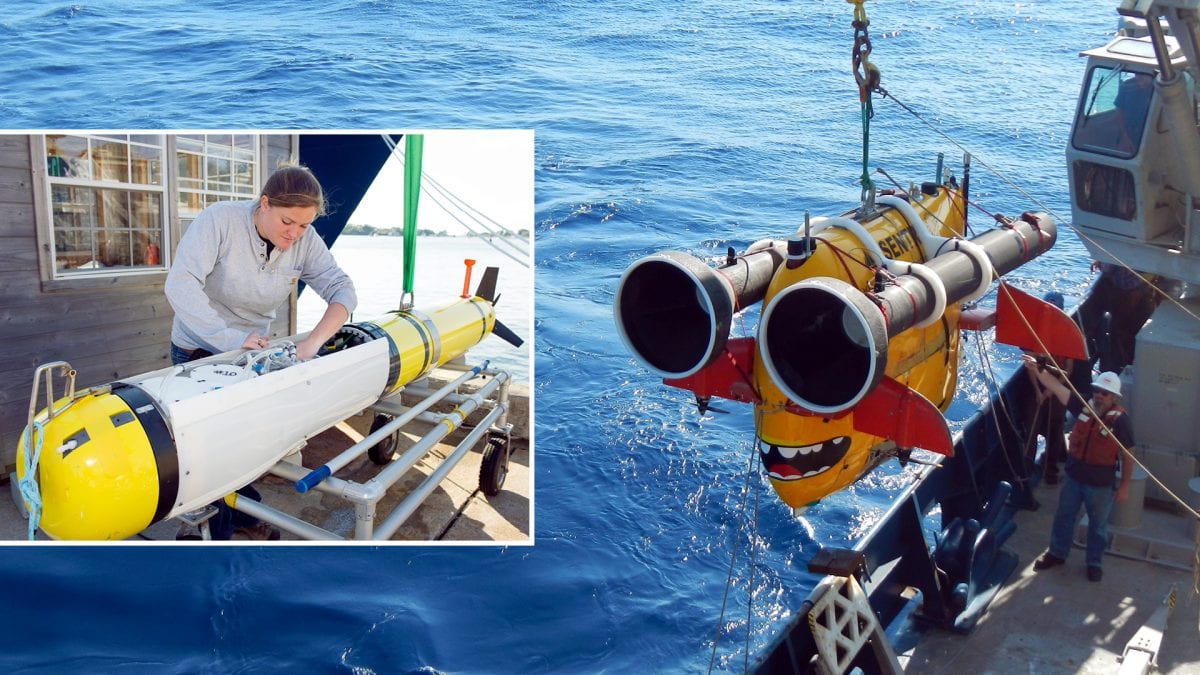

PlankZooka was jointly developed by Cindy Van Dover (Duke University), Craig Young (University of Oregon), and Carl Kaiser (WHOI) for use on WHOI’s deep-diving autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry. Kaiser and WHOI engineer Andrew Billings designed and built a device that uses spinning blades inside tubes to gently pump large volumes of water, containing microscopic organisms, through a net system housed within two carbon-fiber composite tubes. It filters plankton so gently that they remain intact for scientific analysis. It can sample precise areas at depth for long periods of time, filtering enough water to capture relatively rare organisms in the ocean.

The team tested PlankZooka off the U.S. East Coast in July 2015 at a spot more than 1.35 miles deep where methane naturally seeps from the seafloor. The methane is a chemical energy source for animals that can’t use photosynthesis in the sunless depths. PlankZooka collected larvae of sixteen kinds of animals in an eight-hour survey.

Net-based devices are towed on long wires from ships at an angle and can’t get closer than 50 meters from the bottom. By contrast, “Sentry is capable of delivering the new sampling device to within two to three meters of the bottom in more than ninety-five percent of the world’s oceans,” Kaiser said.

SUPR-REMUS is designed to work in shallow waters close to the seafloor to sample larvae of coastal invertebrates such as barnacles, clams, and scallops “in a way that nets can’t do,” said WHOI biologist Annette Govindarajan.

Nets generally mix together organisms collected along a tow. The SUPR sampler (an acronym for “Suspended Particulate Rosette”) was developed by WHOI adjunct scientist Chip Breier and modified by him and WHOI engineer Mike Purcell to be deployed on a torpedo-shaped robotic vehicle called REMUS (Remote Environmental Monitoring UnitS). As REMUS moves through the water, SUPR can take discrete samples at discrete times and locations. Sensors on REMUS concurrently measure depth and seawater temperature and salinity.

“With this sampler, we can initiate autonomous sampling remotely, in response to a change in the environment,” said WHOI biologist Jesús Pineda. In this way, researchers can begin to tease apart fine-scale differences in where and when various types of larvae are located under different oceanic conditions. In March 2014, the researchers tested SUPR-REMUS in Buzzards Bay, Mass., where they detected three different species of barnacle larvae and began to discern patterns of how they were dispersed in the waters.

The National Science Foundation funded development of PlankZooka. Funding for SUPR-REMUS came from a WHOI Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Technology Innovation Award and the Alfred M. Zeien Endowed Fund for Innovative Ocean Research. The team published its findings in the November 2015 Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

Related Articles

- Are warming Alaskan Arctic waters a new toxic algal hotspot?

- The Living Breathing Ocean

- Forecasting Where Ocean Life Thrives

- Illuminating an Unexplored Undersea Universe

- Specks in the Spectrometer

- Setting a Watchman for Harmful Algal Blooms

- Short-circuiting the Biological Pump

- A Telescope to Peer into the Vast Ocean

- Jet Fuel from Algae?