A Telescope to Peer into the Vast Ocean

Epic voyage begins to illuminate the micro-universe across the Pacific

Twenty-five years ago, the Hubble Telescope was launched to look out to the vast darkness of outer space. It captured images of the multitudes of previously unknown stars, galaxies, and clouds of matter, literally expanding the boundaries of human vision and knowledge.

At about the same time, Cabell Davis, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), was thinking about how humans could expand their view into the vast darkness of inner space. He spearheaded development of a remarkable instrument to capture images of the multitudes of tiny, unseen life in the ocean—plankton. The instrument, the Video Plankton Recorder, is about to make a historic voyage, journeying almost 8,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean, to illuminate an unexplored universe of plankton.

Plankton is a catchall term (from the Greek word for “drifter”) that includes bacteria and other microbes, single-celled plants, tiny animals, jelly-like animals, and larvae. The vast majority of marine animal species are plankton for part or all of their lives.

Individually small, plankton are collectively mighty. Single-celled algae produce half the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere. Abundant plant and animal plankton are the heart of the food webs that sustain fish, seabirds, marine mammals, and eventually people who depend on seafood. A key question is how will plankton and ocean ecosystems be affected by ocean conditions that are rapidly changing today. Excess carbon in the atmosphere from fossil fuel burning is being absorbed by the ocean and lowering its pH. Ocean temperatures are also warming, and circulation patterns may shift.

To determine how plankton populations might change, scientists need baseline information about today’s ocean from the smallest scale of the individual plankter to the full ocean scale. Fundamental information about which plankton live where, when, and under what conditions has remained out of our grasp because of the difficulties of finding, identifying, and counting such small organisms in such large ocean areas.

Birth of the VPR

Traditionally, scientists sampled plankton with towed nets, but nets are blunt instruments, mixing the plankton and damaging ubiquitous fragile forms. Moreover, nets capture merely a snapshot of plankton in a particular time and place, often missing patches of plankton, which are unevenly distributed through the sea. The result has been underestimates of plankton abundances.

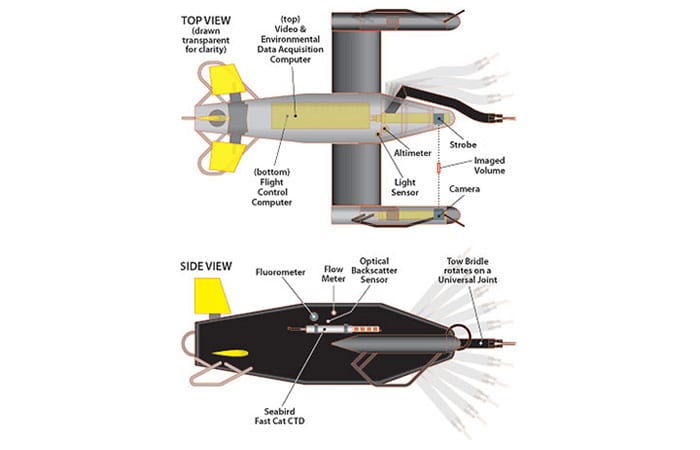

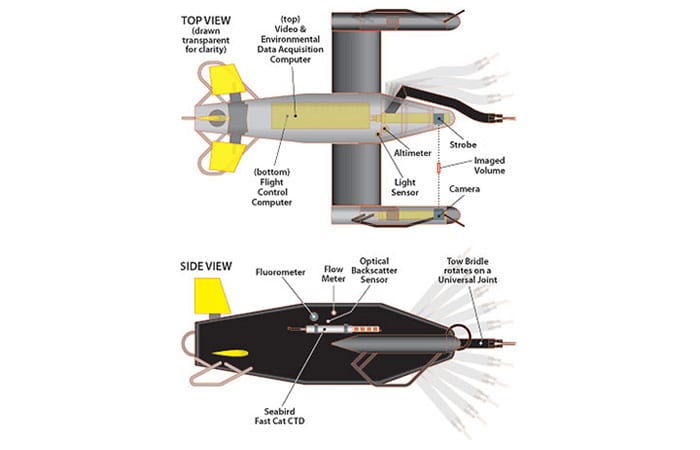

To overcome these problems, Davis, fellow WHOI biologist Scott Gallager, and other WHOI engineers created the Video Plankton Recorder, or VPR, in the 1990s. Essentially, it is an underwater microscope, with a strobe and camera, that’s towed behind a ship. It takes rapid-fire images of the plankton passing through a small area, creating a running video instead of a few snapshots.

“We have two main systems now,” Davis said. “One, the battery-operated Digital Autonomous VPR, can go down to 1,000 meters, and you can tow it at 2 to 4 knots. It records images on a hard disc in the unit underwater. The other, the fast-tow VPRII, will go 10 knots. It’s like a little underwater airplane that flies on the end of a kilometer [0.6 miles] of cable. It undulates automatically up and down in the water, images an area about the size of your little finger, and takes 30 pictures a second. It has onboard flight control. It’s like an engineer’s dream toy! And we get live images and data—the instant feedback is fantastic.”

Across the Atlantic

In 2003, Davis and WHOI engineer Fred Thwaites, who designed the body of the VPRII, towed it 3,000 miles through the Atlantic, continuously sampling across an ocean basin for the first time and demonstrating the instrument’s ability to collect plankton data. The ship steered through warm and cold eddies, based on eddy locations emailed to the ship by WHOI scientist Dennis McGillicuddy. The VPR unveiled unexpected abundances of colonial bacteria called Trichodesmium, which have the ability to convert nitrogen gas into organic nitrogen, supplying an essential nutrient for ocean life.

Melissa Patrician, a WHOI research associate and Ph.D. student at State University of New York, Stony Brook, is using Atlantic VPR data to study plankton aggregations that may attract and supply food for whales, especially the endangered North Atlantic right whales. These data were collected on a second transatlantic VPRII tow, during the maiden voyage of the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor, from the United Kingdom to Woods Hole.

“I don’t think there’s a way to look at the patch dynamics—how, where, and when plankton patches form and disperse—without using an instrument like the VPR,” Patrician said. “I’m hoping we can have a better understanding of how currents and other factors are affecting patch formation, so that we can make predictions about where and when right whales may feed, because they’re so endangered, and management is really important for the species.”

“Understanding the causes and distribution of plankton patches is critical for understanding the entire marine food web and the ways mass and energy are used in the ocean ecosystem,” Davis said.

Across the Pacific

This month, Thwaites, Patrician, and WHOI researcher Phil Alatalo will conduct another first-time VPR exploration—across the Pacific, while Davis collaborates from his lab ashore. In February and March, with support from the Dalio Explore Fund, they will sample on the research ship Alucia, from the Marshall Islands to Panama. They will tow a high-speed VPR that will take color images every six inches over 7,767 miles.

The expedition will yield the first high-resolution data on how plankton species and abundances are distributed across the Pacific, and how plankton populations are related to environmental factors and currents. The team will also focus on links between plankton and eddies—large masses of water spinning like a whirlpool and moving through the ocean—which can bring up nutrients from deep water to the surface and fertilize plankton blooms. The scientists will once again consult with McGillicuddy and WHOI research associate Valery Kosnyrev to obtain satellite data along the way to locate eddies in progress and adjust the cruise track to cross them.

“This cruise will shed new light into the micro-world of the plankton across the vast Pacific Ocean,” Davis said.

Slideshow

Slideshow

The Video Plankton Recorder (VPR) is an underwater video microscope that images plankton and particles in the water as the instrument is towed behind ships. The VPRII system automatically identifies plankton from 500 microns to 3 centimeters in size and displays patterns of how they are distributed in the ocean in real time. (Illustration by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)

The Video Plankton Recorder (VPR) is an underwater video microscope that images plankton and particles in the water as the instrument is towed behind ships. The VPRII system automatically identifies plankton from 500 microns to 3 centimeters in size and displays patterns of how they are distributed in the ocean in real time. (Illustration by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.)- WHOI biologist Cabell Davis stands beside his fast-tow Video Plankton Recorder (VPRII). Davis towed the VPRII nonstop across the Atlantic, while it continuously took images of plankton. (Photo by Melissa Patrician, WHOI.)

- WHOI Research Associate Melissa Patrician and WHOI Research Engieer Fred Thwaites (second and third from left) secure the fast-tow Video Plankton Recorder (VPRII) on the deck of the research vessel Falkor, with crew and colleagues assisting. The team towed the VPRII at 10 to 12 knots across the Atlantic in 2012. (Photo by Fred Marin, Louisiana State University)

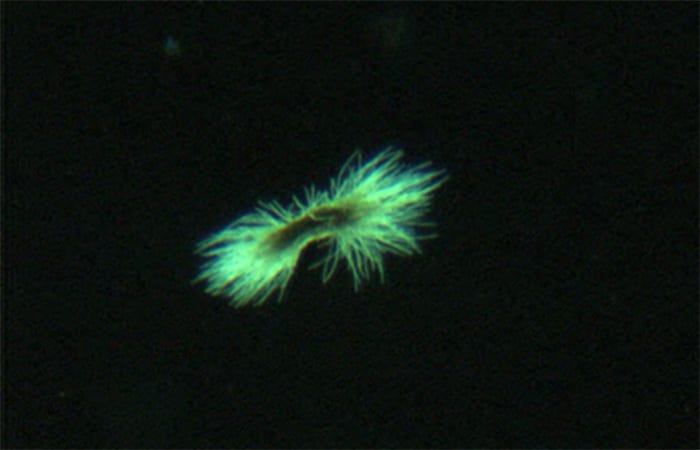

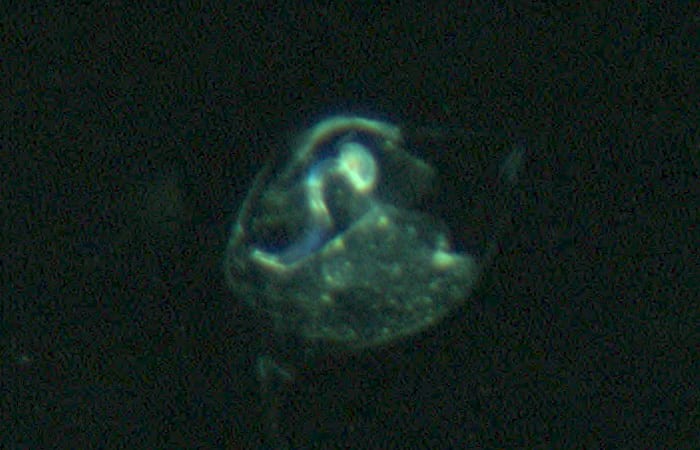

- Trichodesmium are a type of colonial bacteria that form colonies with specific shapes—this one is a "bowtie." Colonies also have "puff" and "raft" (or "tuft") forms and often provide living space for other organisms from single cells to tiny plankton animals such as copepods. The VPR showed that Trichodesmium colonies are abundant across the Atlantic Ocean. They are important to the ocean ecosystem because they have the ability to convert inorganic nitrogen into organic forms that essential nutrients for other organisms. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Copepods are tiny flea-sized crustaceans that are possibly the most abundant animals on Earth. They eat algae and other tiny prey, form large aggregations, and are a critical food supply for fish larvae and other animals, including whales. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

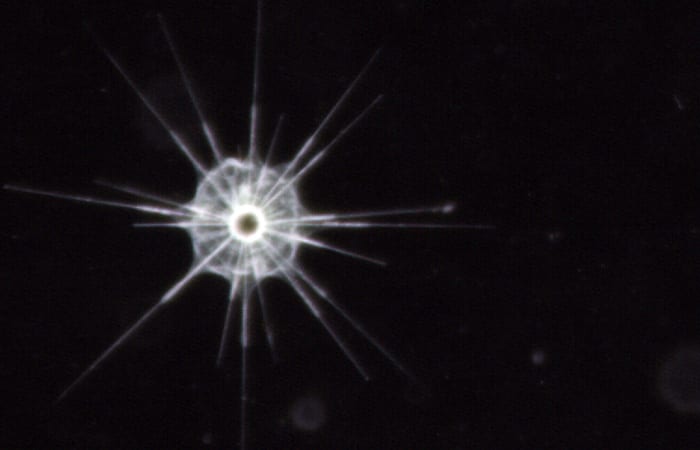

- This star-shaped, single-celled organism is an acantharian. They live in the subtropical and tropical open ocean. They often contain algae that provide their nutrition, but they also consume microbes and other small plankton. They extend protoplasm along their radiating spines to catch food. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- This tiny but abundant crustacean is a copepod called Pseudocalanus, photographed in the North Atlantic. Its red gut and organs are visible through its transparent covering, or exoskeleton. (VPR image courtesy of Betsy Broughton, NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center)

- A shrimp-like krill, about an inch long, swims upward through the frame. Krill are common ocean crustaceans that are vital in ocean food chains. Drifting in the background are single-celled and colonial algae, the krill’s food. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The Video Plankton Recorder captured this sharply detailed color image of a jellyfish called Aeginura grimaldi, a species WHOI biologist Cabell Davis calls fairly rare. Unlike nets, the VPR can record and sample fragile species such as Aeginura grimaldi without damaging them. (Image courtesy of Klas Moller, Institute for Hydrobiology and Fisheries Science, Hamburg, Germany)

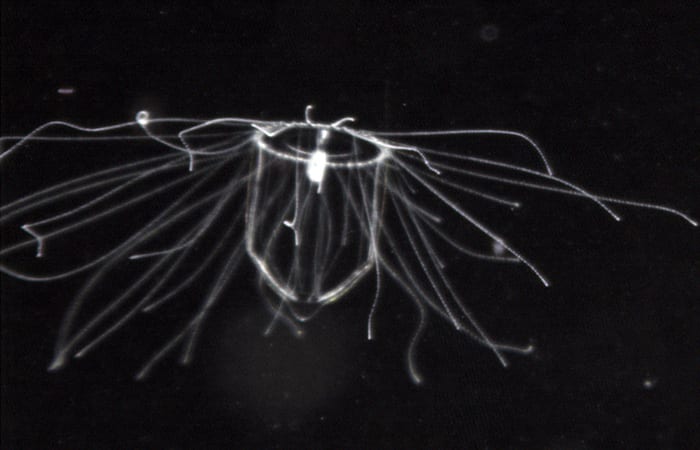

- A delicate jellyfish imaged with its tentacles spread, perhaps waiting to encounter prey. The VPR’s rapid strobe-activated system photographs plankton animals without disturbing them so that they exhibit normal behavior. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Clams and other bivalves produce tiny planktonic larvae that drift until they settle down and become adults. This bivalve larva, a few hundredths of an inch long, swims using cilia—tiny hairs that beat to move the larva. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Worms are common planktonic animals. This one, called an arrow-worm or chaetognath (meaning "bristle-jaw"), is a voracious hunter that swims fast, attacks, and seizes copepods with sharp spines near its mouth. Species of arrow worm can reach four inches long but are usually smaller. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- These planktonic worms, about 1 to 2 inches long, can swim well through the water using paddle-like body extensions, but this one is at rest. The VPR doesn’t produce much turbulence ahead of the instrument and uses a strobe for light, so plankton animals can be imaged undisturbed. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A ghostly sea-angel, Clione is a planktonic snail, or pteropod (meaning "wing-foot"). It is imaged in mid-stroke, with its "wings" (body extensions) flexed away from the viewer. This shell-less snail preys on other pteropods. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

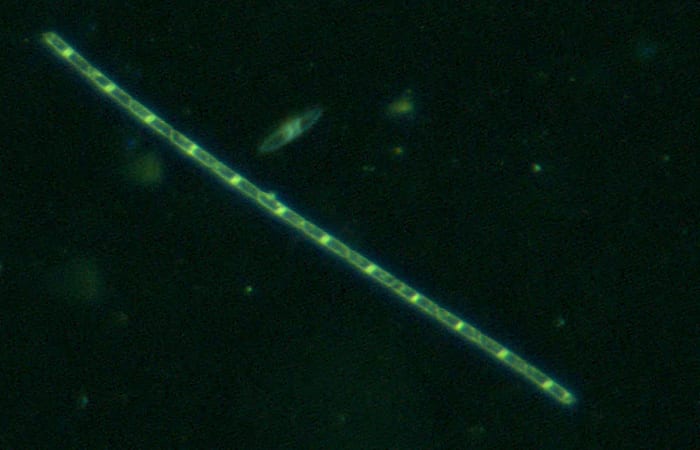

- This VPR image of a colonial chain of diatoms, a type of algae, shows even the individual cells in the chain, itself perhaps only 1/50th of an inch long. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Two microscopc protozoans captured by strobe-flash in the VPRII's focus area. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

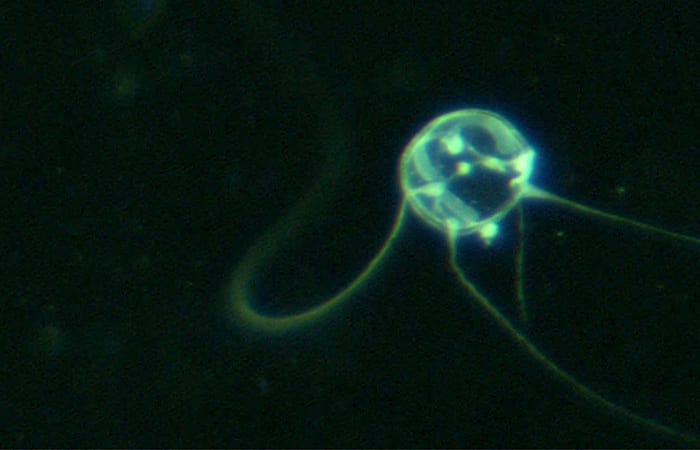

- Look closely to find the tadpole-shaped animal inside a bubble of transparent mucus. The animal is a larvacean, about ¼-inch long and soft-bodied, but it is related to fish. The "head" is actually its body, and it uses its tail to swim and to pull water through the mucus "house," which contains elaborate filtering structures made entirely of mucus. The animal makes its house with secretions, inflates it by wiggling its tail, then consumes particles of food caught on the filters. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Salps are jelly-like animals of the open ocean that often live as colonial chains. Chains of this species, Salpa aspera, swim fast, since propulsion by each inch-long animal adds together. The color VPR captured a sharp clear image of a moving salp chain. (VPR image courtesy of Betsy Broughton, NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center)

- A very small jellyfish, about 1/4" in diameter, with its internal structure visible. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

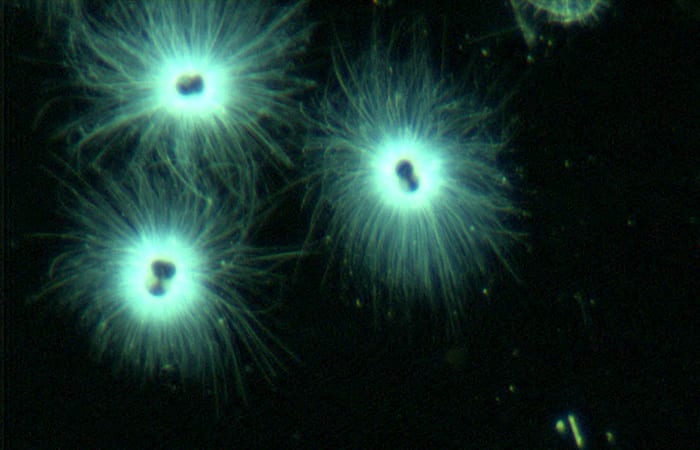

- Three delicate-looking puff balls, actually single-celled protozoans called foraminifera, are barely visible to the naked eye but were imaged by the VPRII. These are predatory cells that capture other single-celled organisms and even larger animal plankton. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A larval stage of an echinoderm, possibly a starfish. The larvae, a fraction of an inch in size, live in the plankton and pass through larval stages until they change to the adult form, when they settle and become bottom-dwellers for the rest of their lives. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

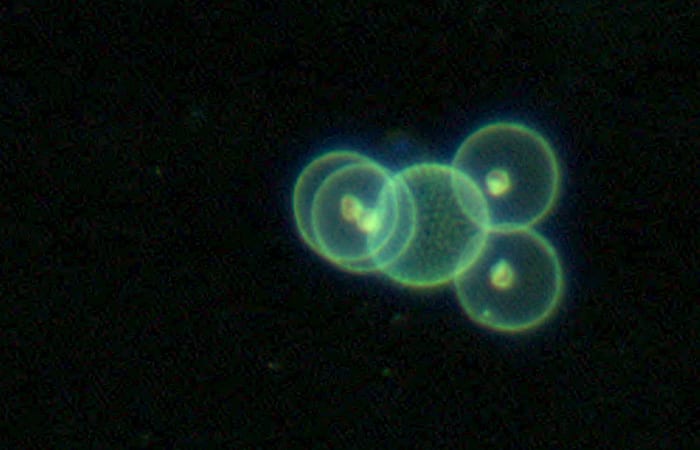

- Spherical colonial protozoans drift by in a group, looking like a collision of planets. (Courtesy of Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

- Are warming Alaskan Arctic waters a new toxic algal hotspot?

- The Living Breathing Ocean

- Forecasting Where Ocean Life Thrives

- PlankZooka & SUPR-REMUS

- Illuminating an Unexplored Undersea Universe

- Specks in the Spectrometer

- Setting a Watchman for Harmful Algal Blooms

- Short-circuiting the Biological Pump

- Jet Fuel from Algae?

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Ocean Microscope Reveals Surprising Abundance of Life Oceanus magazine

- Video Plankton Recorder WHOI Ocean Instruments