Oceans & Climate

The Ocean's Role in Climate & Climate Change

December 1996 — The past decade has brought rapid scientific progress in understanding the role of the ocean in climate and climate change. The ocean is involved in the climate system primarily because it stores heat, water, and carbon dioxide, moves them around on the earth, and exchanges these and other elements with the atmosphere. Three important premises of the oceans and climate story are:

- The ocean has a huge storage capacity for heat, water, and carbon dioxide compared to the atmosphere.

- Global scale oceanic circulation transports heat, water, and carbon dioxide horizontally over large distances at rates comparable to atmospheric rates.

- The ocean and atmosphere exchange as much heat, water, and carbon dioxide between them as each transports horizontally.

The ocean and atmosphere are coupled—their “mean states,” evolution, and variability are linked. Ocean currents are primarily a response to exchanges of momentum, heat, and water vapor between ocean and atmosphere, and the resulting ocean circulation stores, redistributes, and releases these and other properties. The atmospheric part of this coupled system exhibits variability through shifts in intensity and location of pressure centers and pressure gradients, the storms that they spawn and steer, and the associated distributions of temperature and water content. Oceanic variability includes anomalies of sea surface temperature, salinity,* and sea ice, as well as of the internal distribution of heat and salt content, and changes in the patterns and intensities of oceanic circulation. These coupled ocean–atmosphere changes may impact the land through phases of drought and deluge, heat and cold, and storminess.

One example of coupled ocean-atmosphere variability is the El Niño/Southern Oscillation or ENSO. The appearance of warm water at the ocean’s surface in the eastern tropical Pacific off South America has a dramatic impact on weather and seasonal-to-interannual climate. Considerable effort has been dedicated to developing the ability to predict ENSO, including deployment and maintenance of buoys and other observational systems in the tropical Pacific and sustained attention to improving models of ENSO. However, ENSO is but one of the mechanisms by which the ocean and atmosphere influence one another. Such coupling occurs on many time scales, even over centuries. There is growing interest among the oceanographic community in developing a better understanding of the ocean’s role in climate changes on decadal to centennial time scales, and many of the articles in this issue focus on such variability in the North Atlantic Ocean.

There are, as yet, no continuing observations dedicated, as the observing network in the tropical Pacific is to ENSO, to monitoring, understanding, and predicting decadal climate variability involving ocean-atmosphere interaction. Our challenges are to learn from what observations and modeling have been done and to develop strategies for future work.

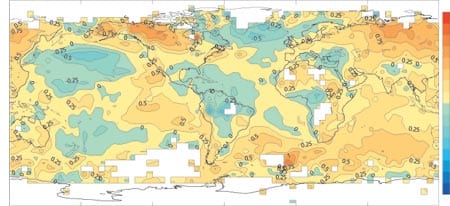

Sustained observations allow scientists to detect climatic spatial patterns. For example, the figure at right shows interdecadal change in land and sea surface temperatures. This figure is taken from the 1996 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, a huge effort of the international climate research community to assess Earth’s climatic state every five years. The predominating orange indicates that the earth’s surface has been, on average, warmer the past 20 years compared to the preceding 20 years. Significant blue areas, principally over the oceans, show that the warming has not occurred everywhere: Large areas of the subpolar North Atlantic are cold, sandwiched between warm northern North America and northern Eurasia, and the North Pacific is also cold, but with a subtropical emphasis rather than a subpolar emphasis.

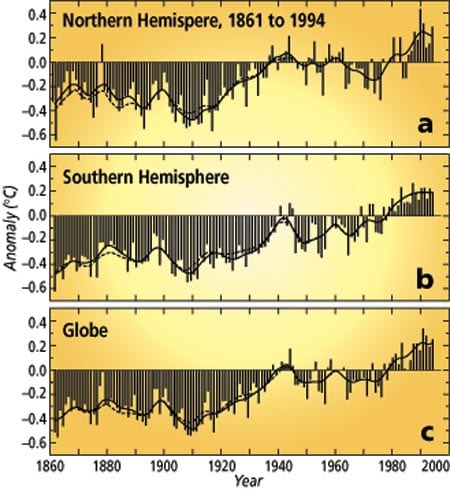

The figure at right puts a longer time perspective on the warming by showing the hemispheric and global average temperature over the past 135 years, the rough limit of useful sustained measurements. These curves show the overall global warming beginning with the industrial age, but note the roughly 60 year oscillation this century, particularly in the northern hemisphere, showing steeper warming trends 1910–1940/1945 and 1975–1995. Time series like these lie at the heart of controversies about global warming as a trend versus as a phase of some mode of “natural” climate variability.

Continued sustained measurements of a broad array of climate indicators will eventually directly answer key questions: Is the steep temperature rise of the past 20 years the portent of a crisis: a rise that will continue through the next century and evolve into an increasingly major climate perturbation? Or is the steep rise “just” a phase of a natural oscillation of the climate system superimposed on a less severe warming? Or is the entire warming trend of the past 135 years itself just the warming phase of a still longer natural oscillation? There is a preponderance of scientific judgement, as carefully compiled and described by the IPCC, that the answer will be somewhere between the first two possibilities, and that this is caused by human impact on the climate system.

This issue of Oceanus emphasizes the North Atlantic Ocean, but, to answer these scientific questions, we must also take on the challenges of filling in many sparsely sampled regions, building on the ENSO work in the Pacific and decadal variability research in the North Atlantic, and working toward understanding on a global basis.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Annual surface temperature change in degrees Centigrade for the period 1975?1994 relative to 1955?1974. This figure, prepared for the 1996 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, indicates that Earth?s surface has been, on average, warmer (predominating orange) over the past 20 years compared to the preceding 20 years. The cooler blue areas show, however, that the warming has not been universal.

- Hemispheric and global average temperature for the past 135 years.

- Scientists aboard R/V Knorr launch a rosette water sampler and conductivity/temperature/depth instrument. Much of the data discussed in this issue was collected by such equipment. Author McCartney is the fellow getting wet at top left.