Knorr Skirts Ice to Search for ‘Arctic Haze’

WHOI research ship helps track pollutants and their impacts near the Pole

In the late 1950s, pilots flying over the Arctic began having trouble seeing long distances, their vision cut short by a mysterious, reddish-brown fog. What they were seeing is now known as “Arctic haze,” a mix of dust, black carbon, and chemical pollutants churned out by factories and vehicles in Europe and Western Asia. With little springtime rain to clear the Arctic air, it tends to float for weeks at a time over parts of Earth’s northern pole.

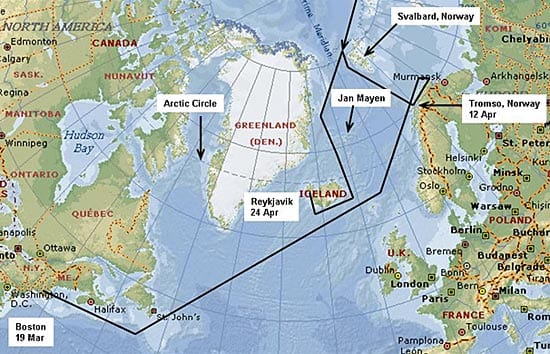

This March and April, crew members on the research vessel Knorr joined efforts with scientists to measure chemical pollutants transported to the Arctic and learn how they may be sparking new chemical reactions in the ocean and atmosphere and contributing to warming in the Arctic. The ship, operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, took scientists 7,394 nautical miles over six weeks on expeditions to sample and study Arctic water and air. It was the northernmost journey on record for the 39-year-old Knorr.

To reach the Arctic, Knorr traveled from Cape Cod through the Long Island Sound, where scientists took air samples to analyze pollution emitted from New York City. The ship then motored across the Grand Banks and Georges Banks bound for the Norwegian coast.

“The weather going across and up was pretty rough the whole way, and we were heading almost right into it,” said Knorr’s captain, Kent Sheasley.

Getting there was slow going. At times, the vessel’s progress was reduced to 3 knots, or about 3.5 miles per hour. But scenic springtime views of Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the west coast of Norway, and finally an area of ice-free Arctic Ocean made up for high seas and gales, he said.

To the edge of the ice pack

Though powerful, Knorr is not an icebreaking vessel, lacking a reinforced hull and the specific bow design for plowing through sea ice. Still, scientists on board needed to get close to the ice pack to compare differences in seawater near and far from the ice edge.

“The chemical reactions involved and ice conditions required for them to occur are not fully known,” said the expedition’s co-chief scientist, chemist Patricia Quinn of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific Marine Laboratory in Seattle. “If we learn more about what causes them, we will most likely have a better understanding of Arctic chemistry in general. This really is basic research and all the implications are not fully known.”

The researchers will examine how chemically reactive industrial particles affect the formation of clouds and the destruction of ozone in the atmosphere, for example. Data from the region are scarce, Quinn said, so gathering current concentrations of pollutants will provide baseline information to gauge changes in the future.

Without icebreaking capabilities, scientists could only skirt the ice edge and relied on Sheasley to navigate Knorr “as close to the ice as he felt safe and comfortable,” said Quinn. In search of this edge, they passed Svalbard, Europe’s northernmost territory, located inside the Arctic Circle.

“We had a fairly large gap in the pack ice, so we were able to get up to 80°14’N latitude,” Sheasley said—a new record for Knorr. “We stayed there for the better part of a day. The visibility was only about four or five nautical miles. It was obviously cold outside while looking at the ice pack, which was about 200 meters off the ship, and we were surrounded by sea smoke. It all added together as a beautiful, quiet, and somehow eerie scene.”

However, incoming reports on sea ice conditions indicated they needed to depart soon.

“As we made our way back south a little, to get around the ice edge, the gap that we had been sitting in closed in, down to the coast of Svalbard,” Sheasley said. “We were lucky with timing, as from then on, we would not have been able to get back up above 80° without running into heavy ice.”

‘Smell my exhaust’

Sheasley also maneuvered Knorr within slender fjords off the northern tip of Norway and Russia so scientists could measure air quality near those countries’ coastal smelters. Once, Knorr sailed downwind of a small fleet of Norwegian fishing boats, and scientists on board turned that encounter into a science experiment.

“I decided to call one of the boat captains to ask if they minded us getting very close, as they had very clean exhaust, and we wanted to check it out a little better,” Sheasley said. “The captain didn’t skip a beat, though I’m sure he thought us crazy, and said ‘I’ll stay steady and you get as close as you want to smell my exhaust.’ It was fairly funny, especially given the language difference, though he spoke very good English.”

Though the crew avoided potentially dangerous encounters with sea ice, there seemed no way to avoid ice buildup on Knorr’s decks, lines, and rails.

“The biggest battle seemed to be keeping everything from freezing,” Sheasley said.

Knorr crew members chipped and pounded away a steady supply of frozen sea spray on the vessel and cleared away snow. This provided scientists safe and routine access to their equipment on deck. Knorr’s forward decks had undergone $240,000 in structural modifications to accommodate 11 heavy, instrument-filled steel containers resembling small mobile homes, called vans.

Each van was secured to decks on the bow, upwind from the ship’s smokestacks, so that dozens of instruments inside, and mounted on their exteriors, could draw in air samples.

“It was a daily routine to thaw out the air and water lines between (scientists’) vans on deck,” Sheasley said. “We also did have ice buildup around the ship, as well as a constant light dusting of snow while in the higher latitudes.”

24-7 sampling

Since returning in late April, scientists have been analyzing 70 sets of collected air filter samples. Additional instruments collected data in real time 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, as often as once per second, so that scientists will be able to analyze concentrations of a multitude of gas and chemical species in the particulate phase.

“We got far enough north to measure Arctic haze,” Quinn said. They highest concentrations of particulate sulfate were measured during the northern-most portion of the cruise, on the edge of the ice pack. The researchers determined that this sulfate was transported from a northern mid-latitude region and found evidence that its source might be burning crops in Eastern Europe.

“Our goal now will be to determine the climate impact of these pollutants and how they, in addition to greenhouse gases, are contributing to the warming of the Arctic,” Quinn said.

These measurements also will provide a baseline for Arctic air quality before further melting of the Arctic ice pack results in more ship traffic and more pollution, said Tim Bates, a research chemist at Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and co-chief scientist on the cruise. Next, Quinn and several other scientists on board will turn their attention to the West Coast, as they prepare to look at air quality off California.

Meanwhile, Knorr departed in May for Iceland to carry scientists studying the explosive springtime phytoplankton bloom on the North Atlantic sea surface. There are no immediate plans for an Arctic return, though the modifications on the vessel have made it ready. Several scientists say they would be willing participants.

“I’ve been on a lot of cruises, and I haven’t yet met a crew with such a can-do attitude,” said scientist Derek Coffman with the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. “They spoiled me.”

The ICEALOT expedition, part of the International Polar Year, was supported by NOAA’s Atmospheric Composition and Climate Program. Funding for Knorr’s modification came from NOAA, the Office of Naval Research, and the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

Before sailing to the Arctic, the research vessel Knorr had undergone $240,000 in structural modifications at a shipyard in South Carolina to accommodate the weight of instrument-filled steel containers resembling small mobile homes, called vans. Instruments inside the vans sampled Arctic air and water, which scientists were studying to learn how pollutants may be contributing to warming in the Arctic. (Photo by Derek Coffman, NOAA/PMEL)

Before sailing to the Arctic, the research vessel Knorr had undergone $240,000 in structural modifications at a shipyard in South Carolina to accommodate the weight of instrument-filled steel containers resembling small mobile homes, called vans. Instruments inside the vans sampled Arctic air and water, which scientists were studying to learn how pollutants may be contributing to warming in the Arctic. (Photo by Derek Coffman, NOAA/PMEL)- Knorr carried scientists 7,394 nautical miles on a six-week expedition that departed Cape Cod in March (track noted in black). It was the northernmost journey on record for the 39-year-old research vessel. At the Arctic expedition's conclusion in April, Knorr reamined near Iceland to assist with another science expedition. (Map and ship tracks courtesy of Daniel Wolfe, NOAA )

- “The weather going across and up was pretty rough the whole way, and we were heading almost right into it,” Capt. Kent Sheasley said about the wavy trip across the North Atlantic in early spring. (Photo by Derek Coffman, NOAA/PMEL)

- Knorr's bosun Pete Liarikos routinely knocked ice from the ship while traveling between Svalbard and Greenland. (Photo by Derek Coffman, NOAA/PMEL)

- During the trip, Knorr stopped in the Norwegian port Tromso, known for snowy weather and colorful seaside homes. (Photo by Derek Coffman, NOAA/PMEL)