Another Piece in the Arctic Puzzle

Latest Ice-Tethered Profiler installed to monitor polar conditions

It’s spring again, and while most of us are putting away our winter coats and watching our flowers pop up, it’s time for Rick Krishfield and Kris Newhall to don their extreme weather gear, zip up to the top of the world, and plant scientific instruments on an ice floe in the Arctic Ocean.

Their recent annual trip to install Arctic monitors was finished in a record 24-hour work-blitz—that is, after delays caused by huge cracks in the ice, which shut down an ice-floe runway, and by a visit of Great Britain’s Prince Harry.

Every year since 2004, Krishfield, a senior research specialist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), has installed Ice-Tethered Profilers (ITPs) in the Arctic Ocean, a region that is warming faster than the rest of the globe. The region’s melting ice causes dramatic local changes to the Arctic and its ecosystem and may also affect the circulation of the ocean and the climate of the planet. But the Arctic’s perennial ice, cold, and sunless seasons hinder access by ships, people, and traditional methods used to study other oceans.

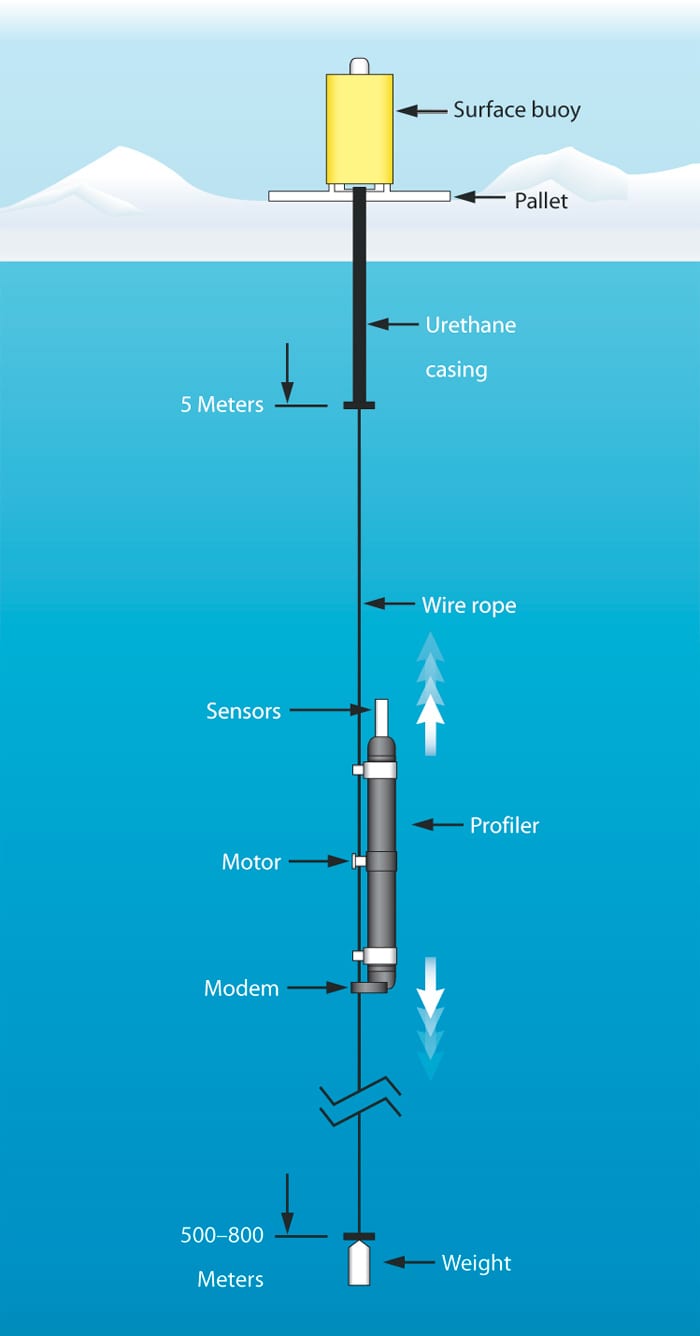

The ITPs, designed by WHOI physical oceanographer John Toole in collaboration with WHOI engineers, go where scientists cannot, examining the ocean below the ice 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. ITPs are sleek sensor-carrying cylinders that crawl up and down a wire attached to bright yellow buoys implanted in the ice. The polar ice cap seems solid but is made of drifting floes that are carried on ocean currents. The sensors measure water temperature, salinity, and pressure, sampling ocean properties from nearly a half-mile deep up to the ceiling of ice. Data are transmitted via satellite to WHOI as soon as they are collected and are immediately available on the ITP website.

International collaboration

In April 2011 Krishfield led a team that included Newhall and WHOI researchers Jeff Pietro and Steve Lambert to the town of Longyearben on the Norwegian island of Svalbard. They then flew to Russia’s Ice Camp Barneo, a research base established annually since 2002 and, since 2008, also an eco-tourism camp. Barneo is rebuilt from scratch each year for a few weeks in April on thick ice close to the North Pole.

Working within this short time window, the WHOI team this year collaborated with researchers Jamie Morison and Dean Stewart from the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory’s Polar Science Center and Sergei Pisarev of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Shortly after arriving at Barneo, the group flew on a Russian helicopter to place four instruments—an ITP, an ice mass balance sensor (which measures changes in ice and snow thickness), a flux buoy (which samples heat and momentum exchanges between the ocean and ice), a weather station to capture atmospheric conditions, and a Web cam—at a site 110 miles west of Barneo.

In this region, Arctic ice, floating on seawater, drifts south towards Fram Strait—the narrow body of water between Greenland and Spitzbergen that marks the border of the Arctic Ocean. The team hopscotched over the Pole to place instruments farther “upstream.” In this way, the buoy assembly will drift longer on the ice, traverse more of the Arctic, and collect more data before drifting through Fram Strait and leaving the Arctic. The drift track of this ITP appears on the ITP site. (It is labeled ITP #47, because it is the 47th ITP deployed, but only the 42nd in the Arctic.)

Drifting with their ice floes for one to three years, ITPs can obtain up to 1,500 profiles, until the batteries in the underwater units run out, the floes drift out of the Arctic, or the ITP is damaged by being dragged in shallow water or crushed by converging ice floes. In general, they are not designed to be recovered, since the cost of seeking them with an icebreaker is prohibitive, said Toole, though they are retrieved whenever feasible. ITP buoys have batteries that last as long as five years, extending the chances that they will be found and recovered from the ice, and their components re-used. Some of these bright yellow upper units, severed from their wire after being caught between floes, have been retrieved after washing ashore on Iceland or Svalbard.

In and out in eight hours

Experience paved the way for the fast installation. “We’re used to it,” said Krishfield, who has 20 years of working in the Arctic and has deployed ITPs from Camp Barneo since 2007. “But this year was the quickest trip yet.”

Krishfield’s scientific colleague Pisarev, who is at camp Barneo every spring, has helped greatly over the years, serving as translator and liaison, as the camp operators have come to know the WHOI scientists and engineers.

“The collaboration has been amazing,” said Newhall. “It has to do with the trust factor. They know us now, know how we work, and are happy to work with us.”

Operations were streamlined this year. Instead of staying at a secondary camp while deploying the buoys—drilling holes through 4-meter-thick ice, paying out wire, testing the communications and software packages—they had enough experience with the instruments and enough manpower to install all four instruments in just eight hours. The weather was also perfect this year, so the helicopter pilots agreed to wait on the ice for them. This was much more comfortable than the previous year, when the helicopter dropped the team off on the ice, where they set up a field camp (which included a camp-encircling warning system to tell them if polar bears approached) and stayed for three days to deploy the instruments.

An ocean-spanning network

Toole’s goal is to distribute and maintain a collection of ITPs throughout the Arctic Ocean. The International Polar Year in 2006-7 initiated a big push to gather current information about what’s happening in the Arctic, and that focus provided researchers many platforms (both icebreaking ships and planes) from which to launch ITPs.

“We envision a loose array of approximately 20 of these ITPs being maintained throughout the Arctic Ocean to observe the annual and interannual variations of the upper ocean,” as well as ocean- or wind-related changes in the direction or speed of the ice drift, Toole said.

“This information is so valuable for climate studies,” Krishfield said. “Most of the data we have is relatively old, back from the ’50s through ’70s. And if you don’t have data every decade, you can’t study the climate change.”

“With the team safely back home,” Toole said, “we’ll be gearing up for several more ITP deployments this summer.” If all goes well, scientists will again achieve the geographical data coverage they covet, at least for this year.

Interruptions both natural and royal

Even with a near-perfect installation, the group had some delays in Svalbard before they could get to Camp Barneo.

“A 3-inch crack developed, starting at Barneo’s mess tent, and ran clear across the runway,” said Newhall. “So the runway was shortened and planes had to travel lighter. We waited in Longyearben for the camp operators to pump water from the layer under the ice, to fill part of the crack near the runway with water that spread and froze,” strengthening the runway like patching a pothole on Boston’s streets.

The researchers were also interrupted by royalty: Britain’s Prince Harry, who had been accompanying a group of wounded British servicemen on a trek to the North Pole, needed to depart from Barneo. The researchers’ flight to Barneo was delayed until he left.

“We saw his plane land from Barneo, and then another plane take off right away,” said Newhall. Something about getting back to England in time for a family wedding.

The ongoing ITP research is supported by the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs. ITP development was supported by WHOI’s Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Technology Innovation Program and the National Science Foundation.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- WHOI researchers and international colleagues return to a waiting helicopter after a long day near the North Pole in April 2011. In just eight hours the team installed four instruments in the ice, including an Ice-Tethered Profiler (ITP), whose yellow buoy is in the foreground. The ITP is the latest in a series of ITPs seeded in the Arctic over several years to continuously sample ocean properties under the ice as the ice floe it sits on, drifts with ocean currents. (Photo courtesy of Rick Krishfield, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Senior research specialist Rick Krishfield "talks" to the ITP to make sure it functions properly before leaving it frozen in the ice floe. Krishfield has long experience working in the Arctic and has placed ITPs there since 2004, working with scientist John Toole, who developed the ITP with WHOI engineers. Toole's goal is to install and maintain a fleet of ITPs in the Arctic, monitoring and relaying how the Arctic Ocean is changing with the region's warming conditions. (Photo by Kris Newhall, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI engineers Jeff Pietro (left) and Kris Newhall attach the cylindrical ITP to the wire that will hang below the yellow buoy (visible at right) when the installation is complete. A battery powers the ITP, allowing it to crawl up and down the wire. The ITP travels from a half-mile deep up to the ceiling of ice while its sensors measure ocean properties, creating a 'profile' of ocean conditions. (Photo by Rick Krishfield, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- ITPs do what humans cannot—measure Arctic Ocean conditions 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, under the ice and through seasons of complete darkness. Developed by physical oceanographer John Toole and WHOI engineers, the ITP system consists of a yellow surface buoy that sits on an ice floe, a urethane-coated wire (attached to the buoy) ending with a weight to keep the wire vertical, and the cylindrical profiler. The profiler cycles along the wire, carrying oceanographic sensors through the water column. Data on water properties are telemetered to shore in near-real time and available on the ITP Web site. (Illustration by Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)