A Buoy’s Long Strange Trip

An oceanographic instrument drifts from the Arctic to Ireland

Western Ireland is cool and rainy in late September—good weather for ducks. Irish filmmaker Fergus Sweeney was walking along Blacksod Bay, County Mayo, last fall, when he saw a big round object washed ashore in the distance. It was bright yellow, the color of a rubber duck, but nearly as a big as a bathtub.

Sweeney took a closer look and saw that it was an oceanographic buoy. But where had it come from, what was it for, and what brought it to Ireland?

Sweeney began digging for information starting with faint markings on the buoy. The trail led up to the North Pole, where the buoy was set into Arctic sea ice in 2011. And it spanned the Atlantic to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), where oceanographer John Toole and WHOI engineers have built a series of specialized buoys to measure ocean conditions in the remote and fast-changing Arctic.

Arctic wanderers

“By the time the buoy washed ashore, the only visible marking was an embossed name of the flotation foam manufacturer, Gilman Corporation,” Toole said. Sweeney opened an access panel, found a GPS module, and took photos for identification.

“Fergus contacted [company owner Elizabeth] Gilman; Gilman contacted WHOI, and we eventually sorted out that it was one of our ITPs,” Toole said.

ITP stands for Ice-Tethered Profiler. These expendable robotic devices are deployed through holes drilled in Arctic sea ice. The buoys on the ice support long weighted lines hanging beneath. A motorized “profiler” unit crawls up and down the line, measuring water salinity and temperature from just beneath the ice to hundreds of meters down, as the ITP rides along with the drifting ice. Electronics in the buoy transmit the data and locations to shore via satellite.

Since 2004, WHOI scientists have deployed more than 60 ITPs to reveal changes in sea ice, seawater properties, ocean currents, and other conditions in the Arctic, even in the frigid, dark winter. They are illuminating a critical blind spot—a region that is difficult to monitor and highly vulnerable to climate change.

Sweeney had many email conversations with Toole and WHOI engineers Rick Krishfield, Steve Lambert, and Kris Newhall. They were able to identify the washed-ashore buoy and re-create its history. As a picture of the buoy’s journey emerged, Sweeney began to conceive of an educational exhibit about the buoy at the local arts center.

This buoy’s life

Most ITPs don’t have long lives—about two years at most. They collect and send data until their batteries fail, their tether lines snag on the bottom and break, their underwater units are stripped off the line, or ice crushes them. This one, identified as ITP 47, was exceptionally long-lived.

“This particular buoy had been used on a previous ITP deployment, recovered, then reused as ITP 47,” Toole said. That caused some confusion when trying to work out what had happened.

In October 2009, ITP 35 was deployed on an ice floe in the Beaufort Sea. It drifted clockwise with the ice, collecting data to 2,500 feet (760 meters) deep, until October 2010, when it was recovered on a return expedition. In April 2011, back it went into ice near the North Pole, this time as ITP 47.

It drifted south and collected and sent data until Dec. 24, 2011, when transmissions ceased. The scientists think that colliding sea ice rode up and over the floe that ITP 47 was on, and buried the buoy.

“At its last transmission, ITP 47 was just north of the northern tip of Greenland,” Toole said. But months later, in May 2012, the buoy started transmitting again. “It was milling about west of Iceland.”

Most of that time the profiler had been doing its job, collecting data. But stuck beneath the ice, it couldn’t relay them.

“It was pushed under the ice and couldn’t get a satellite signal to call home for quite a while,” Lambert said. “Then it popped up between Greenland and Iceland.”

“Once the buoy could again see the sky, it transmitted to us its backlog of profile data, collected between Dec. 24, 2011, and Feb. 28, 2012,” Toole said. The underwater unit stopped recording data then, probably because it was damaged by being dragged on the seafloor.

The surface buoy continued to report its position until early October, when, in hindsight, Toole said, the electronics housing leaked and the instrument stopped working. As for what happened next, Toole could only make an educated guess that ITP 47 was blown eastward by the wind, against prevailing westerly ocean currents, to Blacksod Bay.

Ambassador for ocean science

Arctic ITP buoys have washed up before—in Iceland, Scotland, the Orkney Islands, and Svalbard, Norway. This isn’t unexpected, given an ITP’s lifestyle, but it’s still surprising to anyone who finds one on a beach, as Sweeney did. (Even as recently as Feb. 7, 2014, WHOI received an email from Aodh O’Donnell, director of a furniture company in Skibberen, Ireland, who wrote: “Good Morning. It looks like I have one of your buoys! I found it in West Cork Ireland!”) If undamaged, WHOI investigators arrange for the return of the ITP components, so they may be reused. But after two deployments ITP 35/47 was in bad shape and no longer useful for science.

ITP 47 had already had two lives, but Sweeney made sure it lived on. He retrieved the buoy, created a Facebook page and YouTube video, and worked with local students on an educational exhibit called “Drifted, ITP 47.” It showcases the buoy and its electronics and includes multimedia presentations about ITP 47’s path, WHOI scientists, climate research, and wildlife the buoy may have encountered. The exhibit was shown at Áras Inis Gluaire in Belmullet, Ireland.

“All this work in the exhibit was done by people from Erris,” Sweeney said, referring to the local area. “What Steven, John, and their colleagues do allows us to follow what’s happening in the world’s ocean. Just as we need photographers and people to do art exhibitions, we need researchers and scientists to tell us what’s happening in our planet. I think more people will appreciate their work now.

“The world’s climate is changing, and they are telling us. These types of people inspire people like me, so when I see something washed up on the beach, I say, ‘Maybe I could do something with that.’ “

The ITP program has been supported by the National Science Foundation, WHOI, and several European research programs. “Drifted: the story of ITP 47” was supported by Brendan Murray, artistic director of Áras Inis Gluaire Art Center.

Another Lost Buoy—ITP 6

When Aodh O’Donnell discovered the surface buoy of an Ice Tethered Profiler (ITP) in Cork, Ireland in February, it was the second ITP buoy to come ashore in Ireland. Like ITP 47, this second buoy’s identifying marks had also been largely obliterated during its drift. O’Donnell contacted WHOI, and with instructions from Senior Research Specialist Rick Krishfield, he opened the buoy’s electronics housing and extracted labeled components that identified the system as ITP 6, one of the earliest ITPs launched.

In September 2006 the WHOI ITP group deployed ITP 6, see at left in the photo by Rick Krishfield—along with (center) an Arctic Ocean Flux Buoy that measured heat transfer and (right) an Ice Mass Buoy that monitors ice thickness—on a 9 foot-thick ice floe in the central Canada Basin northeast of Alaska. ITP 6 drifted clockwise with the Beaufort Sea Gyre for more than a year before being carried out of the gyre to the northeast and into the Arctic Ocean.

Summer 2007 saw a dramatic retreat of the Arctic sea ice cover, and the ice floe supporting ITP 6 thinned by melting from more than 9 feet thick to only about 20 inches. We think the heat that caused this melting came from solar warming of the open-ocean waters between ice floes in the regions ITP 6 traversed. Due to the melting, ITP 6’s surface buoy likely sank deeply into its ice floe, leaving little freeboard. Ridges forming in the ice covered the buoy and blocked satellite data telemetry—for 2 months in late 2007 and for 8 months in 2008—but even while buried, the ITP continued to operate, measuring water properties, and logging the data internally. When the surface buoy resurfaced each time, it sent the stored data back via satellite.

The profiler ceased operating in July 2008 when its internal battery supply was exhausted. Over its lifetime, ITP 6 collected 1,335 vertical profiles of temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen. Communication from ITP 6’s surface package ceased for good in October 2009, when the instrument was about 100 miles north of Ellsmere Island, over the continental slope. Presumably currents and wind carried the buoy south and eventually east, to the west coast of Ireland on a track similar to ITP 47’s drift. But the details of that four-year-plus journey after we lost contact with the buoy remain a mystery.

Slideshow

Slideshow

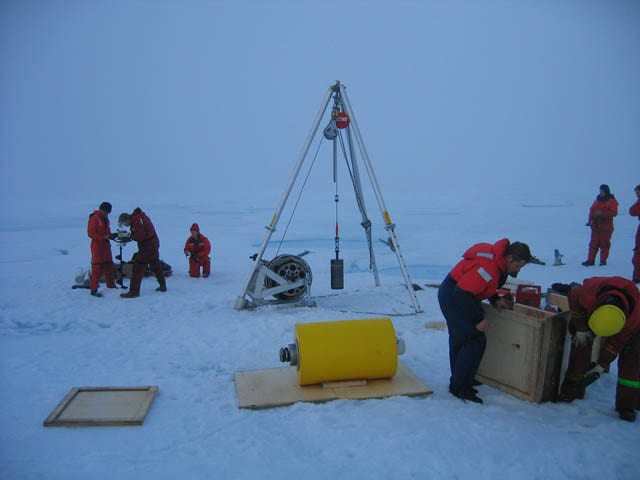

- In 2011 a team from WHOI flew by helicopter to deploy ITP 47 in thick ice near the North Pole. Left there, the ITP drifted slowly with the ice floe. Below the ice, suspended under the buoy, an instrument moved up and down a long, 700-meter line, measuring water properties, while the buoy sent the data back to scientists by satellite. (Photo courtesy of Rick Krishfield, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A bright yellow oceanographic buoy washed ashore in Blacksod Bay, County Mayo, on the west coast of Ireland in September 2013. Local filmmaker Fergus Sweeney discovered it there and followed the clues that led back to the buoy's origin as an instrument from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and revealed the buoy's long, meandering journey from the North Pole to Ireland. (Photo courtesy of Fergus Sweeney)

- Irish filmmaker Fergus Sweeney cleans the buoy of Ice-Tethered Profiler 47. Intrigued by the bouy's history and by WHOI scientist John Toole's research using ITPs to monitor climate change in the Arctic Ocean, Sweeney created a Facebook page and an educational exhibit in a local gallery about ITP 47 and the science behind it. (Photo courtesy of Fergus Sweeney)

- The ITP system is designed so that it may be deployed directly from an icebreaker using man hauling or helicopter ferrying of the equipment to the deployment site, or installed up to 300 hundred miles from fuel depots with a single flight of a small aircraft.

- Together with the tether end weight, the ITP hardware totals approximately 450 kg (1000 lb). Field technicians, emergency survival gear, and the minimum deployment equipment bring the helicopter payload up to 1000 kg (2200 lb). This weight may be transported up to a maximum 280 miles round trip by a medium lift helicopter (such as the Bell 212), or over 600 miles round trip by the DeHavilland Twin Otter airplane. For shorter round trip distances, several ITP systems could be loaded onto and deployed from a single Twin Otter.

- The deployment operations for the first ITPs were supported by the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker Louis S. St-Laurent utilizing BO-105-CB helicopters for reconnaissance to select an appropriate icefloe, and to transport gear and people for the deployment. These particular helicopters can carry up to 4 passengers and have a stated payload (fuel and cargo) of approximately 675 kg (1500 lb), so several flights were needed to transport a single ITP system, deployment apparatus, and personnel.

- Reconnaissance flights to select the icefloe typically include 1-2 scientists (in addition to the pilot and a rifle bearer). Multiyear icefloes are identified, landed upon and drilled (using a 2” hand auger) to determine ice thickness. The ideal floe for an ITP deployment is multi-year ice (which can be identified by the lighter shade of blue color in melt ponds in summer) that is relatively thick (2.5 to 4.5 m), level, and sparsely ponded. Thick floes are thought better able to survive for long time and less prone to rafting.

- ITP systems are transported to their deployment sites in several pieces: surface package, wire tether on aluminum spool, tether end weight, and the Profiler unit.

- A motorized auger is used to create an 11"- diameter hole through the icefloe.

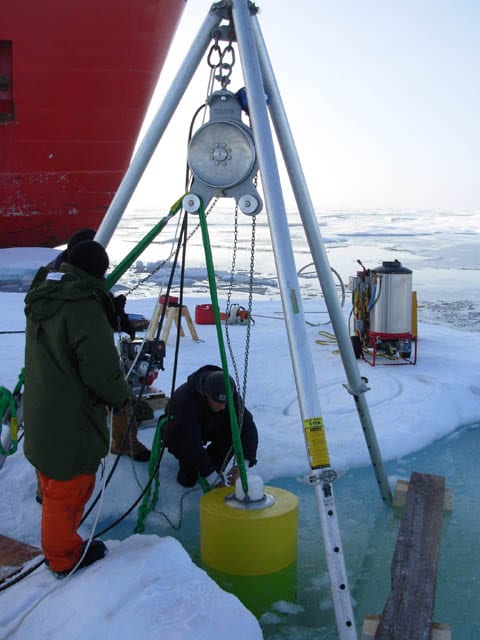

- With the aid of a light-weight, portable tripod, the tether ballast weight and subsurface tether is deployed through the hole.

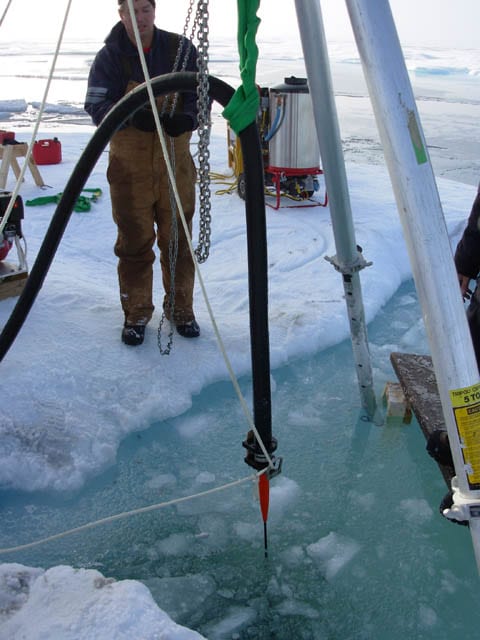

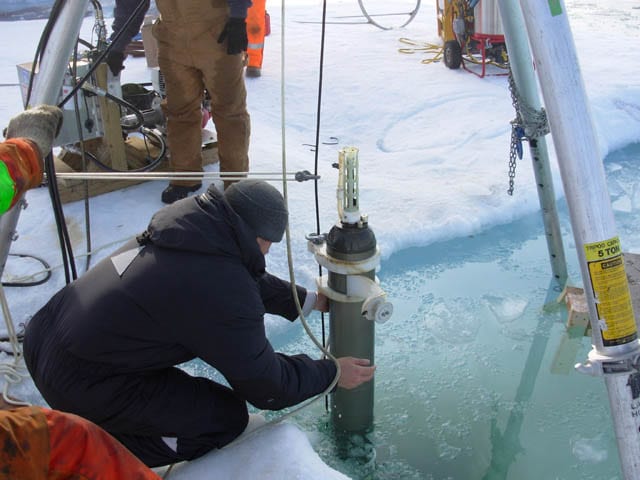

- At a convenient point, the ITP is mounted on the wire (two bracket connections plus the inductive modem bracket) and eased down the wire through the ice hole.

- After making one mechanical and one electrical connection at the surface unit, the package is positioned onto a wooden palette over the hole and the tripod is disassembled. A portable computer is connected temporarily to the surface controller to verify instrument functionality before the technicians depart the site. Based on the preprogrammed sampling plan entered in the ITP profiler, the instrument will then start working.

- Once an ice floe has been identified and all of the gear has been positioned at the site, the ITP deployment operation typically takes between 2-4 hours to complete. From first landing on an appropriate icefloe to last departure, a complete ITP system can be deployed in 4-8 hours.

- Typically after a year in the field, an ITP in summer will be found sitting in a melt pond. Here, cruise personnel are starting to stage for a recovery operation. The orange float and flag in the background were installed during a previous reconnaissance helicopter flight in order to facilitate relocation.

- Helicopters are frequently used to transport the deployment/recovery gear to the ITP site. Here, the water heating unit is being delivered.

- Kris Newhall beginning to assemble the water heating unit.

- More bits and pieces.

- Key to the recovery operation is use of a hot water melt ring. The ring (consisting of a loop of metal tubing attached to a frame) fits over the ITP surface buoy and is held in place by the mooring technicians. Hot water is pumped through the tubing, causing the ice adjacent to the ring to melt.

- Close up of the melt ring at work.

- Rick, Kris and Jim posing with the melt ring apparatus.

- Closeup of the melt ring at work.

- Checking the settings on the water heater and pump.

- Rigged for recovery. The melt ring has freed the ITP from its supporting ice floe and been removed. The deployment/recovery tripod has been set up over the ITP and rigged with a power block. By now the icebreaker has arrived on scene.

- Beginning to lift the ITP system out of the water, together with the remaining cylindrical chunk of ice surrounding the tether left by the melt ring.

- Chipping away at the cylindrical chunk of ice left by the melt ring.

- More power! Using a chain saw to cut away the remaining chunk of ice surrounding the tether.

- The top 5-m segment of the ITP tether is now clear of the water. Note the grounding plate for the sea water return of the inductive modem telemetry link just at the junction between the reinforced top wire segment and normal wire-rope tether below. (Follow the white line that is wrapped around the plate.)

- Surface buoy and top 5-m tether segment recovered. Starting to rig the wire rope tether on the power block.

- Using the power block to haul up the wire rope tether.

- The 790 m of wire rope is simply flaked on the ice floe for later bundling and transport to the icebreaker and disposal. Due to corrosion, re-use of recovered tethers isn't deemed prudent.

- Here the ITP profiling vehicle surfaces, lifted along with the wire by the bottom stop attached to the wire just above the end weight.

- The ITP profiling vehicle ready to detach from the tether. The shackle visible above the wire guide was attached during recovery to control the wire position.

- Closeup of the CTD on the ITP after 2 years in the Arctic Ocean.

- Here the end weight of the ITP tether has been lifted clear of the water. Kris is removing the bottom stop on the wire -- put there to prevent the ITP profiling vehicle from impacting the wire termination flange (orange object just above the weight) and possibly getting stuck. The recovery operation is completed by breaking down the tripod and transporting all the components back to the icebreaker.

Video

Related Articles

- An open polar sea?

- The pull of the poles

- Communicating Under Sea Ice

- Another Piece in the Arctic Puzzle

- Exploring the Arctic in the Midst of Change

- The Icebot

- Knorr Skirts Ice to Search for ‘Arctic Haze’

- Arctic Voyage Tests New Robots for Ice-covered Oceans

- A New Way to Monitor Changes in the Arctic

Featured Researchers

See Also

- Another Piece in the Arctic Puzzle

from Oceanus magazine